Federal courts across the country are increasingly questioning the legality and constitutionality of certain deportations by the Trump administration, even when they appear lawful on paper, as more judges rule and contradict one another.

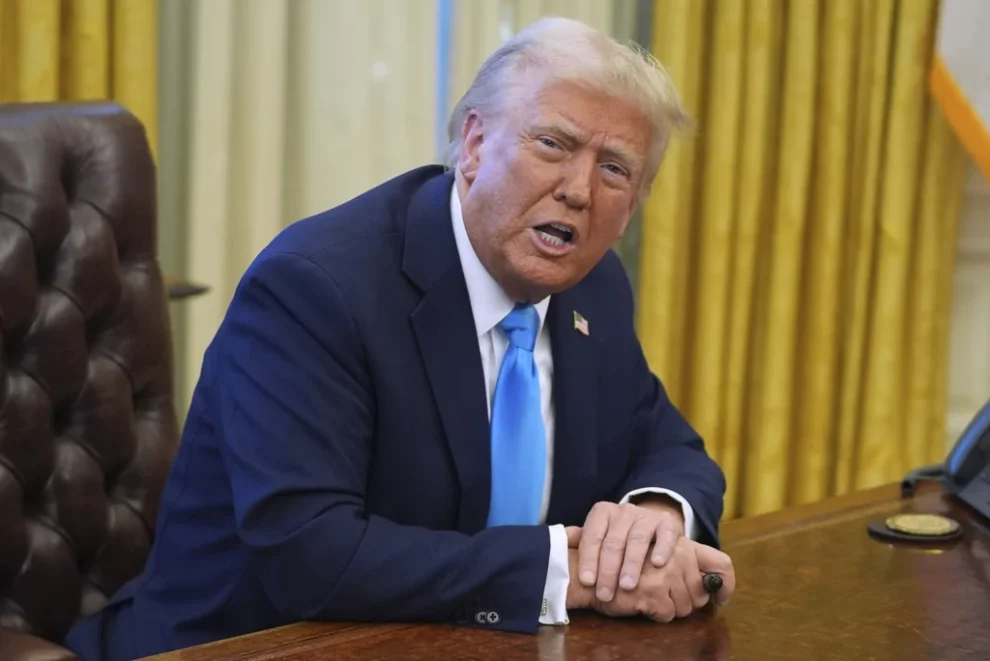

Last week, four high-profile deportation cases sparked rebukes from federal judges against President Donald Trump and his deportation plans, painting a complex picture of an immigration system where law enforcement priorities clash with due process rights and judicial authority. Ultimately, it can become difficult to ascertain when judges are overreaching or when an administration’s mistake must be remedied amid the chaotic web of conflicting decisions.

“Deportations are often analyzed on a case by case basis because sometimes the illegal alien’s factual circumstances call for a closer analysis or additional fact finding,” said John Shu, a constitutional law scholar who served in both Bush administrations, regarding a case involving a Guatemalan who was deported from the United States — only to have a federal judge order the administration to return him this week.

On the flip side, Shu told the Washington Examiner, “what it boils down to is that judges shouldn’t just stop all deportations of illegal aliens en masse merely because they don’t like the Trump administration or because they feel badly for the illegal aliens. The administration has a duty to execute and enforce the laws, including deportations.”

Here is a rundown of the major deportation cases ensnared in litigation this week, and where the issues stand as the Trump administration confronts wins and losses in court.

Abrego Garcia back in US to face human trafficking charges

Perhaps the most contentious case centers on Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran national who was deported to his home country in March despite a judge’s order barring his removal to El Salvador.

Back in the U.S. as of Friday evening, Abrego Garcia has been indicted in Tennessee on federal charges of conspiracy to transport illegal immigrants. Attorney General Pam Bondi held a press conference about the charges on Friday, alleging he ran a human smuggling operation for nearly a decade, claiming he conspired to move thousands of people from Texas to other states.

The government has admitted in court that his deportation was an administrative error. Under the judge’s order, Abrego Garcia could have been legally deported to another country — just not El Salvador, where he claimed fear of gang persecution.

The Supreme Court later ordered the Trump administration to “facilitate” his return to face proper deportation proceedings. He is now in federal custody awaiting further court proceedings and an eventual trial.

Shu emphasized the first Trump administration’s missed opportunity to challenge the immigration judge’s 2019 withholding of removal order barring deportation to El Salvador.

“If DOJ had appealed that 2019 order, which is supposed to be temporary, they likely would have won,” he said. “They can still reopen the order because the factual circumstances have changed since 2019. The gang that allegedly threatened him no longer exists, thanks to President Bukele.”

Even though the White House strongly wanted Abrego Garcia to remain abroad, Trump’s deputy chief of staff for policy, Stephen Miller, vowed that the Salvadoran national would go back to his country of origin if he were convicted of the smuggling offenses.

“MS-13 illegal alien Garcia was correctly deported to his home nation of El Salvador and was subsequently indicted after new evidence of especially heinous crimes,” Miller said Friday. “He is now being prosecuted. After a lengthy prison sentence, it is back home to El Salvador.”

Deporting Venezuelans to El Salvador becomes a patchwork of opposing views

One of the most significant rulings came Wednesday, when James Boasberg, the chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, ruled that nearly 140 Venezuelan men were unlawfully deported to El Salvador under the Alien Enemies Act, a 1798 wartime law that Trump invoked on March 15. The men were flown to the notorious CECOT prison in El Salvador within hours of Trump’s order earlier this year.

While the Supreme Court previously ruled 5-4 that Boasberg lacked jurisdiction to stop the deportations mid-flight, it affirmed that deportees must be given time to seek legal relief. Boasberg’s new 69-page ruling said the men had been denied that right and were deported based on allegedly flimsy or nonexistent gang ties, in the eyes of the judge.

“Significant evidence has come to light indicating that many of those entombed in CECOT have no connection to the gang and thus languish in a foreign prison on flimsy, even frivolous, accusations,” Boasberg wrote.

Though he declined to order their return, Boasberg gave the administration one week to explain how the deportees might legally challenge their removal from abroad. The American Civil Liberties Union called the decision a “critical rebuke” of the administration’s tactics.

Immigration law experts are taking note. Elizabeth Ricci, a partner at Rambana & Ricci and adjunct professor at Florida State University, said the ruling underscores how due process can apply to people who are not even U.S. citizens.

“Even though immigration proceedings are civil, individuals are entitled to due process protections like notice of charges, a hearing, counsel at their own expense, and the right to examine evidence,” Ricci said. “Agencies like ICE are sometimes failing to follow protocol. Courts are stepping in not to stretch due process but to enforce it.”

But Shu countered that, in many cases, the administration could have used Title 8 instead of the Alien Enemies Act, even in complex cases such as Abrego Garcia’s.

“Title 8 gives plenty of flexibility for the Administration to win removal proceedings in front of the administrative tribunal, which satisfy due process concerns,” Shu said. “And if there’s a withholding order preventing deportation to a specific country, the government should either challenge that order or deport the individual to a third country that will accept them.”

An additional wrinkle was added to the fold Thursday when a Trump-appointed judge in California offered a rebuke to the trend of unfavorable rulings set off by Boasberg. District Judge John Holcomb, in a June 2 order, declined to halt Trump’s use of the AEA to deport Venezuelan nationals, warning that the judiciary is overstepping its authority.

The “plain text of the AEA makes clear that the President’s authority … is close to ‘unlimited,’” Holcomb wrote. The court “may not entertain Arevalo’s various challenges to the findings contained in the Proclamation or to the President’s exercise of his AEA authority.”

Holcomb emphasized the law grants the president broad discretion once he proclaims an “invasion or predatory incursion.” Because Trump has issued such a finding, Holcomb concluded the plaintiff is “unlikely to succeed on the merits of his claim that the Proclamation is unlawful.”

The ruling comes ahead of a June 30 oral argument in a related case before the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals in Texas, where Judge James Ho, a Trump appointee, previously criticized the Supreme Court for punting the matter back to his court. Separately, a federal judge in Pennsylvania, also appointed by Trump, previously found that the administration met the legal justification to declare an invasion by illegal immigrants from Venezuela.

A final ruling there could set the stage for the Supreme Court to resolve whether courts can impose due process constraints on presidential power under the AEA — or whether such authority is entirely immune from judicial review.

Family of Boulder, Colorado, firebombing suspect gets surprising relief

District Judge Gordon Gallagher issued a temporary block on the deportation of the wife and five children of Mohamed Sabry Soliman, the Egyptian man charged with firebombing peaceful pro-Israel demonstrators in Boulder, Colorado. He faces 118 charges.

Although Soliman faces hate crime and attempted murder charges, his wife and children, who have no legal basis to be in the U.S., have not been implicated in the incident. Gallagher ruled that deporting them could result in “irreparable” injury to them.

“Moreover, the court finds that deportation without process could work irreparable harm and an order must issue without notice due to the urgency this situation presents,” Gallagher wrote. The judge also set a hearing on a request for a temporary restraining order for June 13 at the federal courthouse in Denver.

The Trump administration said their immigration status warranted removal and noted that Homeland Security officials were investigating whether they had any foreknowledge of the attack.

Shu questioned the strength of Gallagher’s rationale.

“There’s no question the family is here illegally, and the law permits deportation,” Shu said. “Judge Gallagher said deporting them would cause irreparable harm, but it’s not clear what that harm would be.”

Still, separating families is a fact of the process when someone goes to prison.

“If the DOJ wants to investigate whether Soliman’s family or someone else helped him plan or commit these heinous crimes, it has the right to delay deportation for investigative reasons — but that doesn’t change their legal status as illegal aliens,” Shu said.

Guatemalan man back in US after mistaken removal

The administration also faced backlash in a Massachusetts case involving a Guatemalan man identified only by his initials, O.C.G., who was mistakenly deported to Mexico despite warnings that he feared persecution there.

Federal Judge Brian Murphy ordered O.C.G. returned to the U.S., sharply criticizing the government for initially claiming the man was not afraid to go to Mexico. The government admitted it could not identify any officials who had made or received such a statement after previously claiming in court records that O.C.G. made no credible fear claims.

Ricci said the case is a prime example of how the executive branch’s discretion in expedited removals is not unlimited.

“Even national security-related deportations must conform with due process requirements,” she said. “The courts are enforcing that.”

Shu noted that this case also reveals flaws in the system’s design. “Once he’s in the U.S., he gains a whole range of administrative rights, and it’s up to the Justice Department to make their case before an immigration judge—who, notably, works for DOJ,” Shu said. “If the administration believes someone isn’t actually in danger, they have to argue and show that.”

But in this case, the former Biden administration either didn’t argue that, or they agreed with him that, because he was gay, that he would be in danger, Shu explained.

However, Shu said that ultimately under “ordinary circumstances” it’s “not for federal judges to impinge on the Executive Branch’s Constitutional powers and authorities.”

Judicial pushback is a certainty until final rulings at high court

Together, these cases reflect an escalating judicial pushback against what critics describe as an overzealous and sometimes unconstitutional deportation strategy. Even when legal authority exists to deport certain people, judges are increasingly intervening on the basis claimed due process rights, though the Supreme Court could ultimately strike down those conclusions.

ABREGO GARCIA RETURNING TO US TO FACE CHARGES FOR HUMAN SMUGGLING

Yet these recent rulings signal that even lawful deportations must meet constitutional standards. And as the Trump administration continues to expand its deportation efforts, it may find that the courts remain a formidable check on executive power.

“When both Republican- and Democrat-appointed judges reach similar conclusions about the administration’s immigration tactics, it suggests real legal issues are at play — not just political disagreement,” Ricci said.