The Federal Trade Commission is challenging Kroger’s acquisition of Albertsons, saying their merger would be anticompetitive. The Washington Examiner will take a deeper look at what this lawsuit and potential merger would do to food prices – particularly on the cusp of the November election. Part 2 of Supermarket Sweep Up will focus on how this case plays into the larger argument about the power of federal agencies.

The merger between Kroger and Albertsons could ultimately lead to another chip against the armor of the administrative state if the Federal Trade Commission succeeds at contesting the plan.

Earlier this year, the FTC sued to block the $24.6 billion merger, arguing it would create less competition between brands and would lead to reduced product quality, more store closures, and higher prices. Kroger, which argues the merger would actually reduce grocery costs, sued the FTC in Ohio federal court in response, arguing the agency’s in-house adjudication process violates the constitutional separation of powers.

Here is what to know about how one grocery merger fight could further derail the administrative state.

What is Kroger’s lawsuit even about?

Kroger contends that the merger should be adjudicated in federal court, rather than handled by in-house Administrative Law Judges (ALJs), which often are criticized for favoring the legal positions of the agency.

If the grocery store chain’s argument sounds familiar, it is because the Supreme Court recently ruled on a similar matter against the Securities and Exchange Commission earlier this year in the case known as SEC v. Jarkesy, which held that the Seventh Amendment entitles a defendant in a securities fraud case to a jury trial, effectively curbing the SEC’s ability to force disputes before in-agency judges.

“I’m not surprised about this at all,” Case Western Reserve University School of Law professor Anat Alon-Beck told the Washington Examiner of Kroger’s challenge, noting the Jarkesy case “takes a lot of power from the regulators and the administrative state,” and comes at a time when more and more pro-business litigants are taking a sharper aim against regulations.

Specifically, Kroger also claims the in-house judges presiding over such cases are not removable by the president, thus violating the separation of powers as established in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (2010).

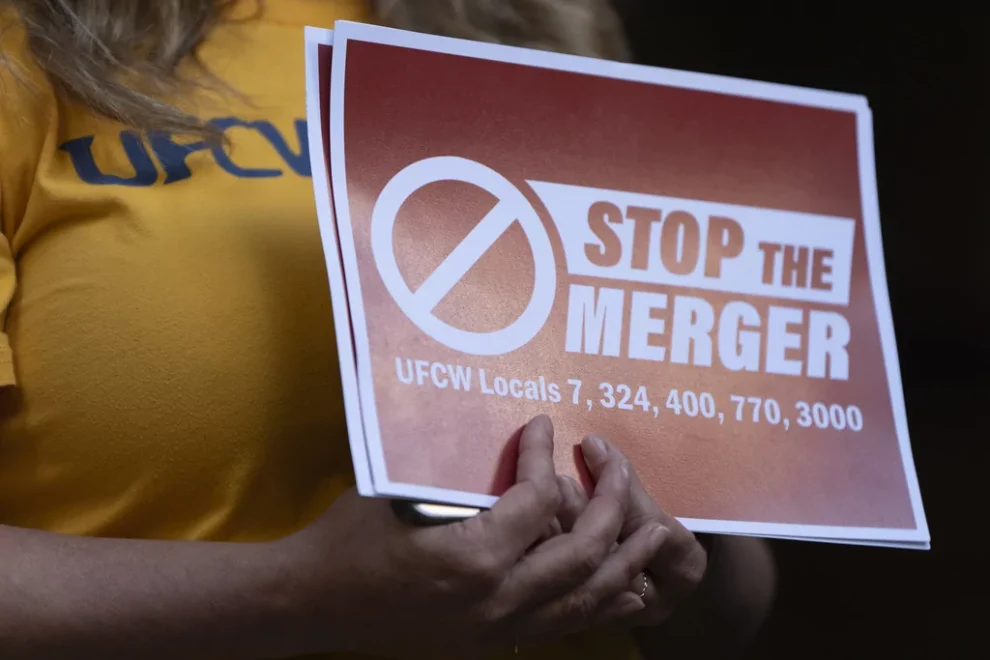

For proponents of heightened regulations on corporations engaging in multi-billion dollar deals, allowing such mergers to be decided by in-agency experts is encouraged because it is seen as protecting ordinary consumers and employees. Labor union leaders, for example, say that workers’ wages and benefits would decline if Kroger and Albertsons could no longer compete.

Conversely, those in favor of more free market approaches could see the status quo of the FTC in-house adjudications to be too restrictive against large business decisions that claim to be beneficial for consumers.

What would a victory for Kroger mean for FTC oversight?

If Kroger succeeded in its challenge against the in-house adjudications at the FTC, it would mark another toppled pillar in a trend against executive agency regulatory powers. Earlier this year, the Supreme Court overturned the 1984 Chevron doctrine, which enhanced the burden on administrative agencies to set regulations and policies by proving that such rules have a basis in legislation passed by Congress.

But the Kroger-Albertsons challenges are currently not just taking place at the FTC’s ongoing administrative trial. There are also separate lawsuits stemming from Oregon, two state lawsuits in Colorado, and one in Washington state. The merger is currently on hold until the Colorado case is resolved.

In some ways, Kroger’s lawsuit against the FTC acts as a failsafe to protect its merger plans in the event that the merger ultimately is struck down by the agency.

In other words, if the grocery chain does not get its way, then the chain’s constitutional challenge in Ohio federal court serves as a backup that could take a legal sledgehammer to the regulatory power house.

“You’re damned if you do, and damned if you don’t,” Alon-Beck said, adding “I think the agencies now, all of them will have to decide how they’re dealing with this, because they’re going to be dragged to court as a result.”

Alon-Beck said the upshot of more rulings against agency procedures could mean that they will need to “revamp their guidelines on antitrust.”

“In some cases, it might not be worth it for them to bring forward [these challenges] because they don’t want their wings to be cut like they did the SEC.”

What does the next chapter look like for Kroger v. FTC?

The next phase of this fight between grocery chains and federal regulators is currently in flux, but the government is pushing for a resolution over the merger before wading into the lawsuit against the fundamental functionality of the FTC. This would be strategic, as it could save higher courts from digging into the chewier constitutional issues that threaten the powers of the agency.

It’s a “push-pull right now in the current dispute,” Michael Murray, a partner and co-chair of the antitrust and competition practice at Paul Hastings, told the Washington Examiner.

Kroger is asking the federal court in Ohio to begin holding hearings in the case as early as Oct. 4, while the FTC, represented by President Joe Biden‘s Justice Department, argues that the Ohio case should only get underway after the merger trial is ruled upon.

“So the FTC wants to go with the merger review trial out in Oregon, and Kroger wants to deal with the constitutionality issue earlier,” Murray said, adding while things can certainly change, the “most likely outcome” is that the merger trial would be heard before Kroger’s constitutional challenge to the agency’s in-house adjudications.

Did Jarkesy really signal a death knell for in-agency adjudications?

Additionally, Murray offered some semblance of optimism to regulators who may feel that the Jarkesy case spelled the beginning of the end for in-house adjudications, noting that the case did not completely rule out the use of ALJs.

“I don’t think it should be over-read to suggest that there’s no role for ALJs or similarly situated officials in administrative agencies,” said Murray.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

While noting the Supreme Court certainly could have gone that direction, Murray noted that the Jarkesy case “needs to be read with that kind of nuance.”

Although Jarkesy shows the courts are skeptical of delegating significant duties in certain claims, it did not rule out ALJs from performing functions that are fundamentally critical to the functioning administrative agencies, according to Murray.