Is Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda at risk for being sued by only casting African-Americans in the role of George Washington in his award-winning musical? According to a new petition before the Supreme Court, he very well might be. Charter Communications, one of the biggest cable operators in the nation, is now telling the Supreme Court that if a recent Ninth Circuit ruling is left in place, white actors could attack Miranda’s magnum opus with viable discrimination suits.

Charter itself is facing a discrimination challenge over its refusal to make any good offer to carry networks owned by Byron Allen’s Entertainment Studios Network. With $10 billion in claimed damages, the plaintiff has survived both a motion to dismiss and subsequent review from the Ninth Circuit. Now, Charter has turned to a legal heavyweight in a bid to get the Supreme Court to intervene. The cable company is being represented by Kirkland & Ellis partner Paul Clement, who was formerly the Solicitor General in the George W. Bush administration.

A cert petition earlier this month (read here) raises two questions.

The first pertains to standards in discrimination suits. Must plaintiffs show that racial animus was the motivating cause of conduct or can they get away with merely demonstrating discriminatory intent as a factor? It’s a question that has attracted the attention of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which says this case threatens to disrupt employment discrimination law by subjecting companies to the tough task of proving that racism wasn’t the reason for hiring or firing decisions.

The second question is arguably even more provocative: Does a cable operator have a First Amendment right to include racial considerations among the factors it evaluates in making editorial determinations as to what programming to carry?

When U.S. District Court Judge George H. Wu first looked at the question, he rejected the First Amendment argument because in his view, the selection of networks on the cable dial doesn’t convey any editorial message.

The Ninth Circuit came to a similar conclusion.

“Our analysis here is limited to cases of discriminatory contracting based on a plaintiff’s race, not contracting based on a plaintiff’s viewpoint,” stated the decision. “A bookstore’s choice of which books to stock on its shelves, or a theater owner’s decision about which productions to stage, or a cable operator’s selection of certain perspectives to air, are decisions based on content, and not necessarily on the racial identities of the parties with which they contract (or refuse to contract). Here, by contrast, Plaintiffs plausibly pleaded that Charter refused to contract with Entertainment Studios due to racial animus, and they must ultimately prove that Entertainment Studios’ racial identity, separate and apart from the underlying content of its programming, was a factor in Charter’s decision.”

In the petition to the Supreme Court, Charter says this is a “false dichotomy.”

“Although decisions about content are often unrelated to the characteristics of the speaker (and generally should be), clearly that is not always the case when it comes to editorial decisions in circumstances where race and content are related,” states the petition. “Indeed, plaintiffs themselves draw a connection between racial identity and content when they assert that their suit is intended to draw attention ‘voices of African American-owned media companies.’”

Charter then brings up examples, telling the high court that Invisible Man and The Color Purple would be very different works if written by white men.

Next, wait for it, comes Hamilton.

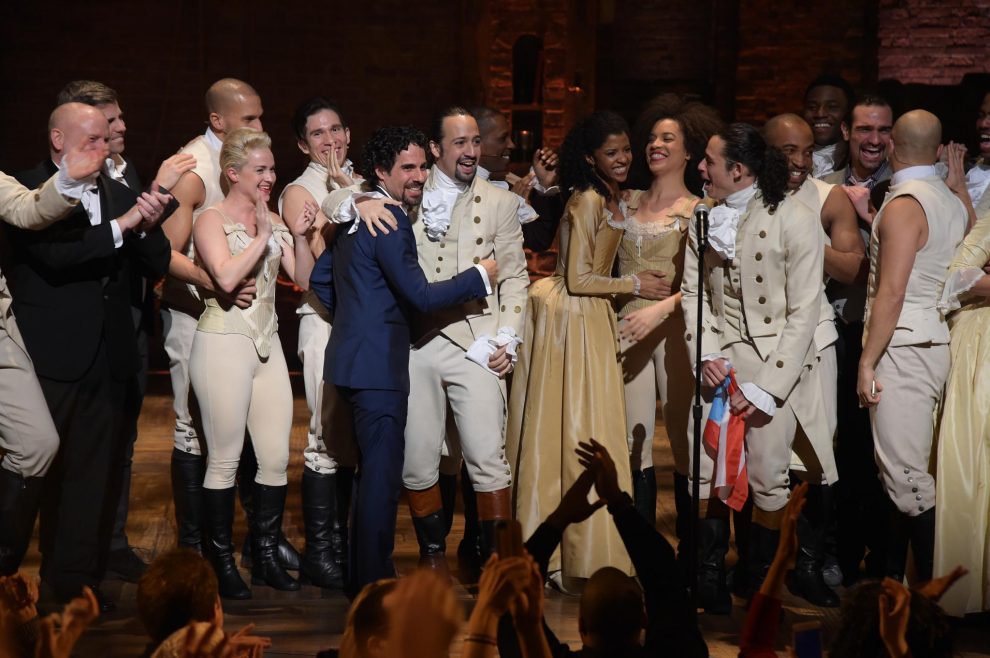

“The musical Hamilton is notable for its creator’s decision to cast exclusively minority actors as the Founding Fathers,” writes the Clement team. “A refusal to contract with a white actor to play George Washington cannot be made an antidiscrimination violation without profoundly undermining First Amendment values.”

Charter later brings up Hurley v. Irish American Gay Group of Boston, a 1995 opinion written by Justice David Souter that determined that parade organizers in Boston couldn’t be compelled to include the participation of a gay group. That decision has been cited often, including when ABC was sued a few years back by African-Americans upset over how lead roles for The Bachelor and The Bachelorette never went to non-white individuals. The case was dismissed.

Allen’s team will surely oppose the cert by distinguishing Hurley from the present situation and repeating the refrain that Charter’s viewpoint isn’t at issue, but Charter believes this to be inseparable and is coming very close to making a racial liberty argument at the Supreme Court. Or at least freedom to include racial considerations when creative decision-making is at stake. In some ways, it’s not terribly far from that baker who refused to make cakes for gay couples. Except this time, the First Amendment argument purports to advance the interests of a racially diverse hit musical.

Allowing a discrimination lawsuit when race places a factor, however small, and ignoring editorial judgment “rides roughshod over First Amendment protections,” states Charter’s brief before concluding, “[I]t would allow even an objectively terrible white actor to bring an action for being denied a part in Hamilton even if factors other than race would provide an obvious explanation for why the actor would not get a part as a Founding Father in the minority cast of Hamilton (or in any kind of cast for any other play). Left in place, the Ninth Circuit’s reasoning will have a devastating chilling effect on the free speech rights of all speech platforms — from magazines, to websites, to bookstores and theaters — that select and promote speech originally produced by others.”

Story cited here.