Though Stanley Tucci is a Hollywood A-lister, starring alongside Ralph Fiennes in this year’s Oscar-contending Conclave, for instance, and in crowd pleasers such as the Hunger Games films, he has cooked up a public persona somehow more associated with food than acting. Tucci has honed a character as a famous epicure that rivals the ones he portrays on film. Few of Tucci’s 5 million Instagram followers are invested in his life today because they fondly recall his Golden Globe-winning role in Conspiracy (2001). They want to know what he is eating.

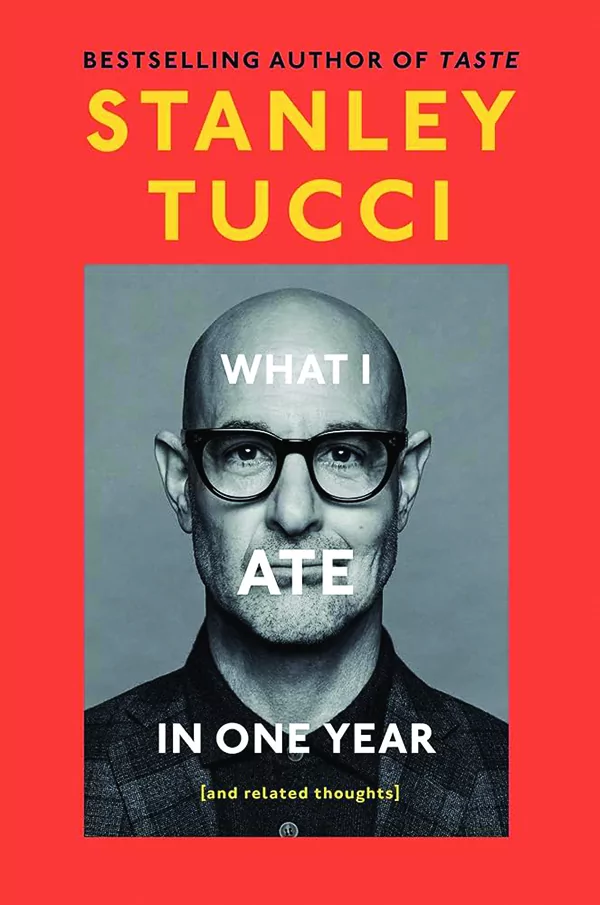

In 2021, he published Taste, a memoir that dwelled more on family dinners than industry dramas. Now, in What I Ate in One Year, Tucci narrows his scope to record one year of journal entries. The collective product is in equal measures public memoir, personal diary, and casual cookbook — supplemented by some poetry in the margins.

Tucci begins the year in Rome on the set of Conclave. He feels nearly at home in Italy, as you would expect for someone whose hit show is titled Stanley Tucci: Searching for Italy. With weeks of restaurant recommendations in the Eternal City, the book could justify its cover price as a travel guide. The intrigue of many days starts and ends with its diet, as Tucci totes his own lunches to a film set while shooting in Italy (Italian studio catering is “dreadful … gross, even”) and waxing poetic about the virtue of soup (“it comforts, it soothes, it refreshes, it restores — soup is life in a pot”).

As a journal, it ostensibly focuses on Tucci’s passion for food and drink. But he is a man of many passions, and he can scarcely talk about one without triggering another. Tucci doesn’t just admire the architecture of Rome, he relates to the young boy who was allegedly brought to tears at the sight of the Pantheon because it was “so perfect.” Nor does he simply enjoy eggs for breakfast — they are “always on my mind” and “practically the perfect food” (even more so if you follow his advice to watch a video of Jacques Pepin making them).

By spending a year with his reader, Tucci builds a personal familiarity that lets his inner life unfold on page over time. As the months pass, food falls into its place as a simple pleasure, a recurring baseline fulfillment, an excuse to reconnect with friends and make memories with family. Using meals as a narrative device brings a grounded sensibility to celebrity voyeurism that would otherwise be at home on Page Six. Ryan Reynolds and Blake Lively come over for dinner, but the real story is how they made chicken cutlets that the children loved. Family holidays would be normal, except the in-laws are John Krasinski and Emily Blunt. Harry Styles drops by for dinner occasionally, earning the description of a fine young man that would make any grandparent proud. Guy Ritchie sounds like a Bond villain redeemed to the culinary light side, replete with an army of Range Rovers to guard his sprawling British estate.

If the daily cycles of pasta and marinara sauce and savory pastries and orecchiette with sausage and broccoli leave a lasting impact on his audience, it might be motivation to actually cook. And to cook often enough to develop an intuition for it. In the Tucci household, meals often start with leftover vegetables or frozen sauces but may evolve into something beautiful.

The results are not uniform, to be fair. Tucci and his wife seem nearly distraught when they make scallops with a skillet too cool to properly sear. He berates himself for inadequately pureeing vegetables in his soup. His reviews of disappointing restaurants are even more scathing, dripping with resentment at money (and, more importantly, time) wasted. Even then, his sense of propriety imposes restraint. Restaurants and chefs he loves are praised, loudly and by name. Subpar establishments are brutalized, but without proper nouns and with descriptions too vague to Google or cancel.

Despite the breezy tone of pasta lunches and celebrity dinner parties, Tucci’s restless inner monologue never permits the weeks to turn glib. As with Marcus Aurelius, a Roman long before the time of pasta, human mortality weighs heavily on Tucci. Living in London, he can estimate the number of times he will see American friends again before they pass. He is 64 but has young children. He is building a life in England with his wife of 12 years, but he can never fully escape his New York home where he raised a family and where cancer claimed the life of his first wife. He won his own battle with cancer, although it left him with deprived saliva production that limits his ability to enjoy rich meats.

Lost in his own thoughts, he admits that he is drawn to the past more than the future. That seems only fitting for the man who insists on proper cocktail hours for guests before dinner and who gripes about T-shirts and streetwear today in a tone that feels more familiar to George F. Will than a Hollywood actor.

Ultimately, one man’s journal is only as interesting as the man himself. And that interest is fully subjective. Nobody can convince me to care what most random celebrities eat or think on a given day. But apparently a nontrivial number of people are keen to hear from Stanley Tucci. Among them was the Manhattan bartender who saw me reading this book with his face on the cover and found herself full of questions. She didn’t care about the means of pasta preparation, but she cared about peering inside his head. “He seems to have a depth to him,” she said.

Any reader of this book will agree.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Will Simpson is a lawyer in New York.