Even in a nation obsessed with representation in the media and politics, the white working class has often gone forgotten. Their economic decline, cultural decay, and frustration with the political system went unnoticed until it helped swing the 2016 presidential election. Yet even as cable news hosts and politicians were completely blindsided, narrative television did a decent job of showing this group’s suffering—even when it wasn’t portrayed accurately.

The white working class has been looked down upon since the earliest days of narrative television. As early as the mid-1950s, TV shows such as The Honeymooners and The Flintstones depicted working-class men as agents of chaos who got themselves into scrapes that their wives or middle-class bosses had to fix. Characters like Ralph Kramden were loud, overweight, and scheming to get ahead, while fathers and husbands on shows that depicted middle-class families—such as I Love Lucy, Father Knows Best, The Dick Van Dyke Show, and Bewitched—were sensible figures who brought stability to their families.

When All in the Family premiered in 1971, the character of Archie Bunker received similar treatment. He was a loud-mouthed bigot who often looked like he was taking his wife for granted and couldn’t understand his countercultural daughter, Gloria, or Mike, his hippie son-in-law.

Yet while Archie wasn’t always portrayed in a positive light, his political incorrectness made him an anti-hero and he was able to lead a respectable lifestyle in a single-income family. Like most men of his time, he was a homeowner who enjoyed strong civic institutions and a union that protected his job.

Archie was able to be cast as an antagonist because his side was then winning. Richard Nixon was in the White House and Archie was the breadwinner: though he battled the younger characters on the show, he still commanded a level of respect. They disagreed with his conservative values, but they respected him enough to wait for him to eat dinner, serve him a drink or cigar after work, and never sit in his favorite living room chair.

That level of protection afforded to working-class white men began to erode in the 1970s as they bore the brunt of a changing global economy. In the fifth season of All in the Family, Archie’s union goes on strike and he becomes dependent on his family for income. In one scene, his wife Edith is cutting his hair while Archie reflects on how fearful he is of the future. It was a side of Archie, and most working-class white men, not usually depicted on scripted television.

The 1970s were a time of immense economic growth, but it was extremely uneven. More than 15.6 million new jobs were created from 1972 to 1980, but most were in white-collar professions. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, white-collar workers saw their employment expand by 30 percent while for blue-collar workers it was less than 8 percent.

At the same time, wages also began to stagnate. From 1948 to 1973, productivity increased by nearly 97 percent and hourly compensation grew by 91 percent. Wages began stagnating quickly afterward, and by the early 1980s, they were in a solid decline for middle- and low-wage workers. For those like Archie with a high school diploma or less, median wages fell from $16.88 in 1980 to just $12.76 per hour by the year 2000, according to a study by the Congressional Research Service.

After a few episodes, the strike ended and Archie got a raise. But as Michael pointed out to Gloria, even a 15 percent raise for the next three years couldn’t match the rising costs. A few seasons later, Archie lost his job for good after 30 years in the union. He ended up on his feet when he used a second mortgage on the house to become the co-owner of a bar.

While Archie as bar owner would go on to a successful spinoff called Archie Bunker’s Place, younger members of the white-working class wouldn’t have the same kind of savings to fall back on. The slow decline of “hardhat men” was on clear display decades before politicians became aware of it.

The visibility of working-class white families fell significantly after All in the Family. It took about a decade before Hollywood produced a trio of shows that gave serious attention to the demographic, with the creation of Married… with Children in 1987, Roseanne in 1988, and The Simpsons in 1989. Until they premiered, American TV had focused instead on the upper-middle class, with programs like The Cosby Show, Growing Pains, and Family Ties.

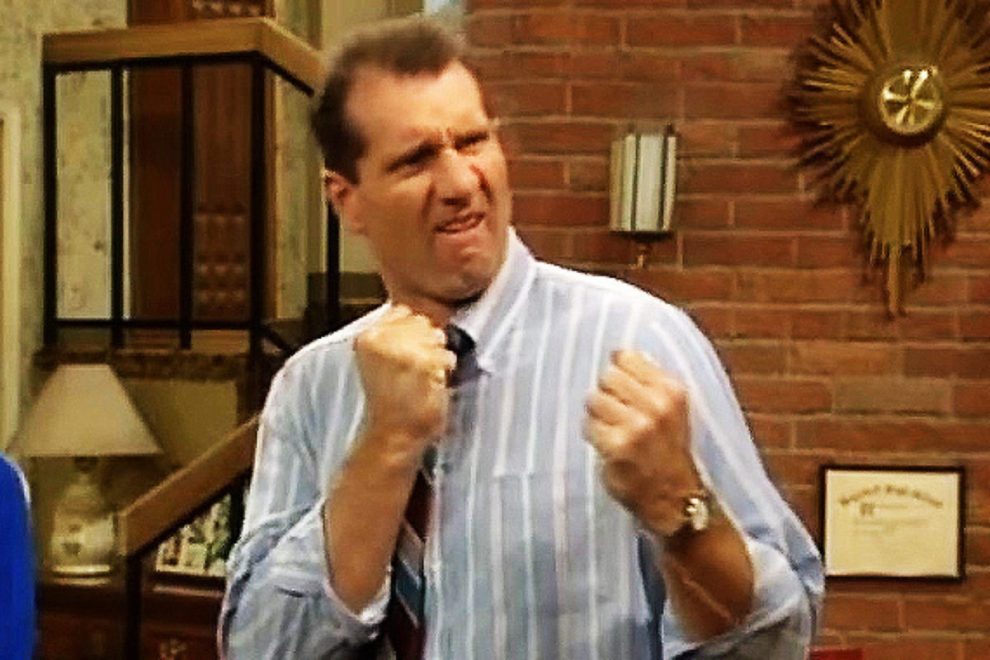

Married with Children’s Al Bundy put a farcical twist on working-class men’s loss of social standing. He was a shoe salesman making menial wages while living amid the consumerism that swept America during the 1980s.

Al was a cultural throwback. He demanded recognition, social status, and respect, but was looked down upon by his family and neighbors for his working-class lifestyle and less-than-respectable living situation. The only way the Bundys could attain the materialism they desired was by stealing, showing the desperation of working-class people to keep up with the Joneses.

Al channeled the frustration he had with his life and economic status into attacking the role that feminism was playing in society. In the first season, Al asks his neighbor Steve, “When did men become such losers? It used to be so great to be a man. Women were there to please us, they’d look after the kids, and we’d go out and have a good time. That’s the natural order of things. What happened, Steve? I’ll tell you what happened, Steve. Someone told women that they should start enjoying sex, too. Now they like it but it’s work for us. Everything’s work for us. It’s this equality thing, it’s killing us.”

Al was living in a post-second wave feminist world. He believed his economic and cultural misfortune could be blamed in large part on the rise of the women’s movement. In later seasons, he even started an organization called the National Organization of Men Against Amazonian Masterhood or NO MA’AM. This move was made in retaliation after his bowling night was turned into a women’s only night and his favorite strip club turned into a women’s coffee bar.

While society claims that white men have advantages in the workforce that are not afforded to minorities and women, those advantages are based more on class than race or gender. According to a study by the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, white men working in blue-collar professions have more competition from minorities and barriers to entry based on their education. In nearly every state, white women are more likely to receive a white-collar professional job than white men, especially those lacking a college degree like Al. This has created broad resentment against many different groups, and, for Al, the target ended up being feminists.

Roseanne was a far less daft perception of working-class life. The punchlines were set up so that the fans laughed with the Conners rather than at them, unlike on Married with Children. The title character, Roseanne Conner, was a Midwestern wife and mother of three living in a post-industrial town. With her husband, Dan, she struggled to keep the lights on.

Over the course of the show, Roseanne bounced between jobs after leading a walkout at the factory where worked in the show’s first season, while Dan worked as a dry-waller. The few times the Conners were afforded opportunities to move up the economic ladder, it was through an angel investor. Dan briefly owned a motorcycle shop after a former friend gave him the funds needed to get the business off the ground, but within a season it fizzled out, and both Dan and Roseanne found themselves unemployed. Roseanne later became the co-owner of a luncheonette after her mother put up the money. The idea of pulling yourself up by your bootstraps was not a possibility for families like the Conners.

This feeling of being stuck amid economic circumstances trickled down to the Conner children. Not wanting the life their parents had, Roseanne’s oldest daughter Becky worked hard in school and dreamed of escaping her hometown. In the show’s fourth season, when she was looking to apply for college, her parents had to break it to her that she couldn’t afford to go. The teenager then lashed out, asking what all her hard work had been for, and told her dad that his economic woes “blew it for everyone.” She eloped with her high school sweetheart, Mark, a deadbeat with few prospects, and ended up living in a mobile home back in Lanford.

Roseanne was one of the earliest shows to explore the idea that surpassing one’s parents on the economic ladder is not so simple for those in the working class. The Conners’ other daughter, Darlene, does fare better, going to art school, starting a career in publishing, and moving to Chicago. But after she lost her job, she found herself back in Lanford living with her parents. Solutions like tax cuts and trickle-down economics can’t help the Conners in the ways they would have helped other TV families at the time.

Roseanne dealt with many political themes, but the only time it actually engaged with a politician was when the titular character met a state representative going door-to-door. She told him, “Why don’t you just go down to the unemployment office and meet them all at once?” The politician’s solution for the community’s economic decline came right out of the supply-side playbook: offer companies tax cuts and a pool of labor that doesn’t demand union wages. Roseanne said, “So they’re gonna dump the unions so they can hire us at scab wages and then for that privilege we get to pay their taxes?”

These are the voters who made up the base of the Democratic Party for decades, the same voters they abandoned in exchange for cosmopolitan liberals, college-educated suburban women, and minorities. Nearly 7 million of these working-class whites switched their votes to Trump in 2016, just like Roseanne inevitably did when the show returned in 2018.

At the premiere of the reboot, audiences saw the Conner family in almost the exact same situation they were in 20 years before. Roseanne and Dan, now seniors, were struggling to get by and unable to afford their medication. Their three older children were all working various dead-end jobs.

This is the unfortunate truth for the blue-collar life. Workers with only a high school diploma saw their incomes drop by nine percent from 1996 to 2014, and their children were likely to find themselves in a similar financial situation. According to New York University sociologist Michael Hout, blue-collar workers’ children were overwhelmingly likely to end up as members of that same economic class.

The 1990s offered more representation for the white working class than any other time on television. Hit show Grace Under Fire, which premiered in 1993, featured a single mother in recovery from alcoholism. King of the Hill rolled out in 1997, an animated show that explored the life of a working-class neighborhood in Texas centered on Hank Hill.

Unlike other shows of its era, King of the Hill made its family patriarch the clear conscience and moral center of his friend group and family. Hank was a middle-aged propane salesman who found himself uncomfortable in a changing world that runs counter to his traditional conservative beliefs.

A large chunk of the show revolved around Hank trying to relate to his sensitive and eccentric son Bobby, who preferred stand-up comedy, music, and modeling to traditionally masculine interests like beer, cars, and girls. In one episode, Hank tried to fix Bobby by telling him, “This is a carburetor. Take it apart, put it together, repeat until you’re normal.” When Bobby got his first job selling soda, Hank said, “If you weren’t my son, I’d hug you.”

The show also tackled the subjects of race and immigration, when, in the first season, a family of Laotian immigrants moved next door to the Hills. The well-to-do new neighbor Kahn looked down on the Hills as ignorant rednecks, while Hank held stereotypical views of Asians. When Hank refused to go to their barbecue, his wife Peggy said he must or people will think he’s a racist. Hank responded, “What the hell kind of country is this where I can only hate a man if he’s white?”

King of the Hill might have premiered nearly two decades before the 2016 presidential election, but the show was already exploring an issue central to President Trump’s victory. Cultural, economic, and racial changes caused a massive shift in the opinions of working-class people over the last few decades. By the time the 2016 presidential election rolled around, according to a WSJ/NBC poll, 48 percent of white working-class Americans said, “Things have changed so much that often they feel like strangers in their own country.” And less than a third of Republicans said they were comfortable with the societal changes that have made America more diverse.

The feeling of grappling with cultural change is a theme explored by the white working class on television. Unlike characters on older shows like Archie Bunker, Hank found himself increasingly on the losing end of the culture war. Yet unlike on other animated TV shows, Hank is never vilified for his conservative values and they aren’t dismissed as being too old-fashioned.

In the opening credits of every episode, Hank is seen standing outside his home drinking a domestic beer with his middle-aged white friends Dale, Bill, and Jeff, as the world progresses without them. This probably wasn’t an intentional choice by the creators, but it is certainly reflective of the experience of white working-class men at the turn of the century. They’re preparing for a future they’re told they don’t belong in, where they’ll be a racial minority and better-off white liberals will tell them to “check their privilege.”

The 2000s featured more family-friendly depictions of the white working class, including Malcolm in the Middle and The Middle. These shows were slightly different from previous sitcoms because the vantage point was often taken from the experience of a child growing up among the working poor.

On Malcolm in the Middle, the titular character and his three brothers live in a working-class community in suburban California. Their parents, Hal, a low-level white-collar worker, and Lois, an employee at a convenience store, struggle to keep food on the table, something they remind their sons of constantly. Their working-class experience is not only felt in the lack of physical comforts like a new car or expensive vacation, but also in the stress it creates within the family dynamic.

Lois’ and Hal’s jobs make them miserable and make the boys think that to grow up means to live a miserable existence. In the show’s first season, Malcolm takes an aptitude test. Because of his 165 IQ and photographic memory, the guidance counselor tells him he can be anything he wants. Malcolm imagines several jobs from the vantage points of his parents, where work never leads to anything fulfilling.

In the series finale, Malcolm graduates high school and is accepted into Harvard University but can barely afford it even with scholarships and working several jobs before, during, and after class. Prior to his graduation ceremony, he’s offered a lucrative career as an alternative to school. Before he’s even allowed to consider it, his mother tells him he has to go to school and work to end up as president.

She explains her logic by saying, “The life you’re supposed to have is you go to Harvard and you earn every fellowship and internship they have, you graduate first in your class and you start working in public service—either district attorney or running some foundation and then you become governor of a mid-sized state and then you become president.” She continues, “You’ll be the only person in that position who will ever give a crap about people like us. We’ve been getting the short end of the stick for thousands of years and I, for one, am sick of it.”

Malcolm asks why he can’t just buy himself the presidency and have the easy life. Lois says, “You don’t get the easy path. You don’t get to just have fun and be rich and live the life of luxury.”

It becomes obvious that the working class are no longer looking to traditional parties and politicians to solve their economic and cultural crisis. The promises of a better life delivered through neoliberalism and meritocracy never materialized for people like them.

Narrative sitcoms about the white working-class family died off with these shows, replaced by reality shows like Here Comes Honey Boo Boo, Ax Men, and Ice Road Truckers. These programs served to further “otherize” the experience of the working poor as ignorant, filthy, and a subordinate class. The few times that television producers decided to again focus on the working-class experience, it came in the form of a feminist experience, as with Two Broke Girls, or by focusing on working-class minorities, as with One Day at a Time; Love, Victor; and Atlanta.

The last long-running narrative show about poor white families is the dramedy Shameless, now in its eleventh and final season. The show follows the life of an unemployed, alcoholic, and drug-addicted single father named Frank Gallagher and his six children who live in Chicago’s South Side. Shameless provides a darker look into poverty, including mental illness, crime, drug abuse, incarceration, gentrification, and homelessness.

It also shows life for the white working poor in the aftermath of what Charles Murray called “the big sort.” Unlike families on shows like Roseanne, All in the Family, King of the Hill, and Malcolm in the Middle, the Gallaghers don’t have an upper-middle class neighbor looking down on them. They live in a poor ghetto where other families such as the Miklovichs have it far worse than they do. There’s no angel investor grandparent or family friend who can make their lives a little better.

All this creates pride in being part of the ghetto, or, as they say, “being South Side.” There’s open hostility and even mockery when any of the Gallaghers try to move themselves up the economic ladder. When the eldest son Ian goes to college, he’s asked to prove that he hasn’t lost his “South Side edge” by committing a crime against yuppies who have moved into the area and are raising the cost of living. Characters openly admit they live depressing lives, but it’s the only thing they feel like they own, even if it’s not theirs.

The assumption is that life for the working class involves living shamelessly to get past the circumstances of their birth and attain a decent living standard. The social institutions once afforded to the working class have completely broken down. And what replaces the lodge meetings, churches, and homeowners associations is the welfare state.

Lip echoes this when he yells at his sister Fiona for investing their money with the hopes of getting a job as a club promoter. When she comes up short, Lip tells her, “When you’re poor, the only way to make money is to steal it or scam it!”

In the later seasons of the show, Frank decides he needs to fix his life and work to establish a relationship with his youngest child. He takes a job at a home improvement store that he finds fulfilling, but as with many brick-and-mortar businesses, he finds it can’t compete with the internet. At a jobs fair, he sees a line full of middle-aged white men who spent their lives working for corporate America. Seeing how he can’t get ahead, the only path he sees to avoid sweeping the floors is by going back to being shameless and running a prescription drug ring to Canada.

After Trump won the presidency, the show changed and tried to be more politically woke. During the 2018 election cycle, Frank earns beer money putting down and picking up lawn signs for a black and a gay Hispanic congressional candidate. Both tell him they prefer to hire more urban people. Even though Frank has spent his entire life on the South Side of Chicago, his skin color precludes him from being part of the working-poor experience.

This isn’t the first time that Shameless had tackled liberal hypocrisy. In earlier seasons, Carl Gallagher couldn’t get into military school because all the available slots were left open for non-white applicants. Frank’s youngest son, Liam, who’s black for a reason the show never fully explains, is only accepted into an expensive private school to fill a diversity visa. Both children are extraordinarily underprivileged, but only one receives special treatment because liberal tolerance for the poor is only skin-deep.

Yet then the show’s writers went and threw most of their genuine storylines away to portray the white working class as racist, because Trump was in office and that’s what Hollywood must do. Frank drafts his own candidate, a former congressman named Mo White who has a long history of advocating for working-class ethnic whites, to run against the candidates who told him he didn’t fit their racial quota. Frank plays into some of the themes that Trump campaigned on in the 2016 presidential election and, when White wins despite being down in the polls, a local news anchor says it’s because people weren’t telling pollsters they were “bigots.”

On hearing he won, Frank asks White what he plans on doing when he gets to Congress, and he replies, “Not a damn thing.”

There’s some truth there to how the white working class perceives politicians who promise to fight for them. But more importantly, it’s how writers and producers of shows like Shameless think of the white working-class voters they talk about on their shows. The characters are either apolitical, having accepted their future in the dustbin of history, vocal progressives, or bigots.

In a world where Trump pervades every part of our culture and the left believes all institutions have a responsibility to fight against him and his supporters, it’s unlikely we’re going to see many more accurate TV portraits of white working-class families. Yet that doesn’t mean their struggles are less real than they were before he was elected. The general decline and desperation exhibited from All in the Family in 1972 to Shameless in 2011 shows they need more focus, not less.

Story cited here.