There’s a small and unremarkable park in a suburb just south of Dublin‘s city center, surrounded by modest semidetached homes and featuring a basketball court and a soccer pitch.

A proposal to rename Chaim Herzog Park in Rathgar has become the nexus of a long-standing spat between Ireland and Israel, and a headache for the superpower with which both countries enjoy a “special relationship” — the United States.

For the U.S., it’s a torn between two lovers scenario. Israel and Ireland both have long histories of mutual affection with America and have large American diaspora communities that are political powerhouses.

Both countries have an economic stake in the outcome: Israel does not want the boycott language some Irish have embraced to become contagious. Ireland is also Israel’s second-largest trading partner, buying $3.89 billion in Israeli goods in 2023. The U.S. bought $103.76 billion in goods from Ireland in 2024.

Several lawmakers in Congress, Democrats and Republicans, have warned that Ireland could face economic sanctions should it push ahead with laws aimed at isolating Israel.

“Their one-sided approach to Israel could damage the relationship between the U.S. and Ireland,” Rep. Josh Gottheimer (D-NJ) said in an interview. Gottheimer has targeted a bill in Ireland’s Parliament that would enhance sanctions on Israeli companies that facilitate Israel’s presence in the disputed West Bank.

Park naming controversy exacerbates hard feelings between ‘I countries’

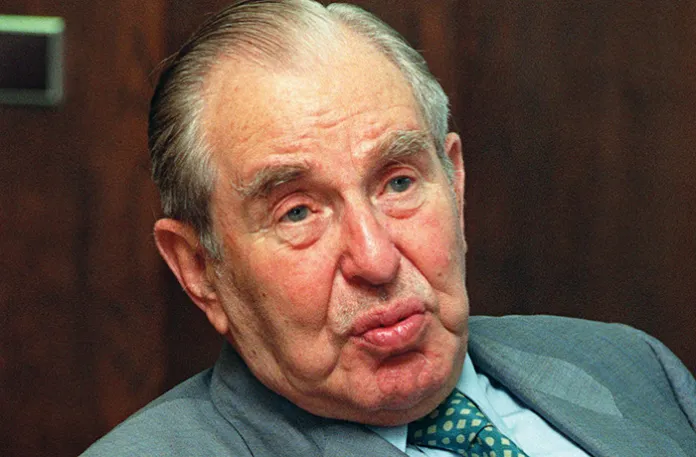

The late Israeli President Chaim Herzog was born in Belfast to Rabbi Yitzhak Herzog, a renowned scholar who served as Ireland’s chief rabbi and later as Israel’s chief rabbi. Herzog was decorated for fighting with the British in World War II. He joined the British army in part because Ireland remained neutral, and then fought for Israel’s independence. His presidency, from 1983 to 1993, was mostly ceremonial.

Herzog’s namesake Dublin park, in a neighborhood where much of Ireland’s tiny Jewish population is concentrated, was dedicated in 1995 when the retired Israeli elder statesman visited the country.

An attempt by some municipal councillors in Dublin to strip the park of Herzog’s name as a means of protesting Israel’s war with Hamas in the Gaza Strip has drawn condemnation, both in the U.S. and, notably, among Irish politicians who have been the Jewish state’s fiercest critics.

“The Government has been openly critical of the policies and actions of the government of Israel in Gaza and the West Bank, and rightly so,” Irish Foreign Minister Helen McEntee said in a Nov. 29 statement, just days before Dublin shelved the proposal, at least for the time being, because of a procedural error. “Renaming a Dublin park in this way — to remove the name of an Irish Jewish man — has nothing to do with this and has no place in our inclusive republic.”

Such statements brought a degree of relief to Ireland’s Jews, numbering less than 3,000, said Maurice Cohen, the chairman of Ireland’s Jewish Representative Council. He has described a community increasingly under siege because of Ireland-Israel tensions since Hamas launched a war against Israel on Oct. 7, 2023.

“There were statements by the Taoiseach [Prime Minister Micheál Martin] and the Tánaiste [deputy prime minister Simon Harris] and the foreign minister, to say that what was happening with the renaming of Herzog Park is wrong and it shouldn’t be happening and it shouldn’t be proposed by the council, and they certainly went as far as to declare it as being antisemitic,” Cohen said.

But Cohen cautioned that the relief Irish Jews felt at how the episode got resolved was mitigated to a degree by the perception that the condemnations came about because of pressure from U.S. lawmakers and, by extension, President Donald Trump’s administration.

“They have got pressure from various politicians from Washington and Capitol Hill, and this certainly does worry them, because they’re very familiar with the Trump administration” and its pro-Israel outlook, he said. “And they know what could possibly happen if they step too far.”

Some of the most pointed criticism came from Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC), who is among the lawmakers closest to Trump.

“When you think it couldn’t get any worse in Ireland regarding animosity toward Israel and the Jewish people, it just did,” Graham said in a long Nov. 29 X post. “I don’t know what the people of Dublin are trying to say, but this is what I hear: A complete turning upside down of history when it comes to the Jewish people and the state of Israel. Modern Ireland is a beautiful country with great scenery, but unfortunately, it has become a cesspool of antisemitism.”

Such lashing out by prominent Americans of influence has rattled Irish Americans who advocate their ancestral homeland.

“There is legislation on the books,” said Brian O’Dwyer, a New York City lawyer who is the vice president of the advocacy group Irish American Democrats, regarding laws and regulations in close to 40 states mandating boycotts of entities that boycott Israel.

“There are people who are calling for the boycott [of Ireland], especially some of the right-wing Republicans,” he said. “I think the danger is real.”

Gottheimer said the prospect of economic penalties on Ireland was indeed real. He spoke on Dec. 3, just after presenting his concerns in a meeting with Irish Ambassador to Washington Geraldine Byrne Nason.

“If they go ahead with this law, they will have a BDS law,” he said, referring to the boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement targeting Israel. “Then suddenly, 38 states in the United States won’t be able to do business with Ireland.”

Gottheimer was the lead author of a letter 23 Congress members sent in October to Martin, warning of consequences should Ireland press ahead with a bill that would add teeth to existing laws banning trade with Israeli businesses.

“This legislation threatens to inflict real harm on American companies operating in Ireland,” the letter said. “If enacted, it would put U.S. firms in direct conflict with federal and state-level anti-boycott laws in the U.S., forcing them into an impossible legal position and jeopardizing their ability to do business in Ireland.”

The letter also cited Ireland’s submission this year to the International Court of Justice to expand its definition of genocide. The court is considering a South African petition accusing Israel of genocide in its war against Hamas in Gaza. Efforts to expand the definition of genocide are seen as a means of securing a conviction against Israel.

Separately, Rep. Claudia Tenney (R-NY) led an August letter with 14 House GOP colleagues to Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, asking for an assessment of whether Ireland would be susceptible to sanctions should the Irish Parliament pass a bill enhancing the boycott of some Israeli businesses.

The bill, advanced by Harris, among others, appears to be stalled and is unlikely to be advanced this year.

Trump-era US-Ireland tensions

Scott Lucas, an American professor of international politics at the Clinton Institute, University College, Dublin, said there have been periodic threats from Republicans since Trump began his second term, not just over Israel, but about Irish laws targeting hate speech and over Ireland’s trade surplus, a major Trump sore point. (In 2023, Americans exported $22.4 billion to Ireland, and Ireland exported $62.6 billion to the U.S.)

Lucas said the disputes eventually fade because the ties between the U.S. and Ireland are too intertwined to disrupt. Hundreds of American companies, particularly those in the pharmaceutical industry, headquarter their European operations in Ireland due to its favorable tax laws.

“This comes up every few months, but there’s just too much that the countries need” from one another, Lucas said. “Onshoring the U.S. companies, bringing them back from Ireland, is hugely difficult for people, and it doesn’t make a great story.”

Lucas pointed to a Nov. 27 op-ed in the Irish Times by Edward Walsh, the U.S. ambassador to Ireland, lauding the relationship as a signal that the Trump administration is ignoring the noise.

“It is a friendship borne of history and culture, but today it is also a dynamic economic and strategic partnership,” Walsh said in the op-ed, arguing that Ireland is the U.S.’s most effective “interpreter” on the continent.

But another November op-ed in the Wall Street Journal by Robert O’Brien, Trump’s first-term national security adviser, struck a markedly different and sour tone, focusing particularly on the recent election of Catherine Connolly, a strident Israel critic, to the presidency of Ireland.

“Ireland is finding its voice in international affairs, but it’s one that seems increasingly hostile to U.S. interests,” O’Brien said, calling for an end to Ireland’s “free ride.”

“Ireland is the most antagonistic country to Israel in the Western world,” he said, among a litany of indictments he listed.

Larry Donnelly, an American law professor at the National University of Ireland in Galway, said the threat of American sanctions is real and ominous.

“One out of every six private sector jobs here is dependent upon the presence of us multinationals,” he said. “And when you look at a piece of legislation that has been considered now — there are reports now that it may be dropped — but something like the Occupied Territories Bill, which would be viewed as falling afoul of some of the anti-BDS laws that exist in the United States? Those laws have teeth.”

Notwithstanding the delays in considering the renaming of Herzog Park and in the passage of the occupied territories bill, Ireland will likely remain among the most critical nations in the West of Israel’s policies vis-a-vis the Palestinians, said Bette Browne, a journalist who has for years covered U.S.-Ireland relations.

The mid-19th-century Great Famine that killed millions of people, the result of neglect and at times outright hostility to Ireland by its British rulers, has seared itself into the national consciousness, Browne said.

“One of the legacies is that these people survive in our consciousness, and the notion that if somebody is out there without anybody supporting them, their cause is just,” she said. She noted the hero’s welcome Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky received when he visited Ireland in the first week of December, a signal of the revulsion the country has for Russia’s invasion of his country.

Boycotting is a natural default for the Irish, Browne said, noting that the term originated in the country in the late 19th century and was named for a British enforcer of evictions who was driven out of the country when his employees and his providers cut him off en masse.

“Boycotting is kind of a big thing here,” she said. ”It comes from that notion of resisting through peaceful action.”

Four decades of Ireland-Israel acrimony

Israel and Ireland, in their first decades, regarded one another as somewhat akin: small, fierce, and proud nations shucking off oppressive British rule. Eamon de Valera, the Irish statesman, forged relations with early Zionists and visited Israel in 1950; in 1966, Irish Jews planted a forest in Israel in his name. Herzog’s father, the chief rabbi, was a champion of Irish independence.

The friendliness redounded among the American diasporas, Jewish and Irish, said Stella O’Leary, a powerhouse advocate who founded Irish American Democrats in the 1990s and remains its president. The first person she sought advice from when setting up her lobby was Tom Dine, then CEO of the powerful American Israel Public Affairs Committee. (Dine confirmed the meeting.)

“We had a great time, and the biggest piece of good advice he gave me was first and foremost, ‘never speak to anybody on the phone or anywhere else about anything to do with the PAC other than what’s in your mission statement,’” she recalled. “‘Don’t discuss any other subject.’ Well, I come home, we start the PAC, we get the stuff out. First phone call was from a guy who said, ‘You’re Irish, you’re Catholic, what is your position on abortion?’ ‘We don’t have a position on abortion,’ I said, just as Mr. Dine told me. ‘Peace, justice, and prosperity in Ireland, and that’s it. Forget it. I’m not discussing abortion with you or anybody else.’”

O’Leary was not concerned at the prospect of any rift developing between the Irish American pols she backed and the Jewish pols she admired. Politicians, she said, play it safe.

“They need more than the Jewish community to get elected, and they need more than the Irish community to get elected,” she said.

Relations between Israel and Ireland have soured since at least the 1980s, when Ireland sought to consolidate its international role as an advocate of the oppressed. The Irish were leaders in the movement to boycott South African goods until apartheid was dismantled.

Palestinians soon became a favored cause, especially among nationalists who sought to wrest Northern Ireland from British rule; driving through Roman Catholic neighborhoods in Belfast, one was almost as likely to see a mural depicting a Palestinian hero as an Irish one. Recurring tensions between the Israeli army and a contingent of Irish peacekeepers who have been in the country for close to 50 years have not helped.

Irish figures bristle at claims that their criticisms of Israel cross over into antisemitism. A heated filmed exchange in Israel between Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Saar and the Irish ambassador sparked a rebuke on Dec. 4 by Martin on the floor of the Dáil, the Irish Parliament.

He objected to what he described as a with-us-or-against-us posture by Israel.

“If you’re not onside, you’re offside,” he said.

That binary, with us or against us, is what Irish Jews and defenders of Israel face at all times, Gerald Howlin, an Irish Times columnist, said in March.

“Part of the problem is the decibel level here of discourse around the Middle East generally and Gaza specifically,” Howlin wrote, expressing sympathy for a Jewish community under siege. “Little is said below the level of shouting. There is no space left here for either a broader perspective or nuance.”

The blunt anti-Israel rhetoric was evident at the Dec. 1 Dublin council meeting, during which councillors railed against the decision to shelve the renaming, with some refusing to believe it was an honest procedural error. One councillor blamed the “Zionist lobby,” another blamed the Israeli army. Neither cited any evidence.

The searing outrage was also evident on Dec. 4 in the decision by Ireland’s broadcaster, RTE, to stay out of the Eurovision song contest next year because Israel would be allowed to participate — stunning for a country that has hosted multiple song contests, and where watching and voting for the home team is a national pastime.

USCIS FREEZES IMMIGRATION REQUESTS FROM 19 COUNTRIES

Cohen said the effect of monolithic criticism of Israel was stifling.

“We’re going through a scenario where the media and the politicians are operating where there’s only one opinion, one narrative allowed on many things, but especially on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” he said.

Ron Kampeas is a journalist based in Arlington, Virginia. He was JTA‘s Washington bureau chief for more than 20 years and previously reported for the Associated Press from its Jerusalem, New York, London, and Washington, D.C., bureaus.