As she walks her election tightrope, Kamala Harris is wobbling between supporting unpopular President Joe Biden and distancing herself from him. The dangers of this high-wire act were apparent on Oct. 8 when she was asked on The View whether she would’ve done anything differently from Biden. She gave a long pause and said, “There is not a thing that comes to mind,” adding, “I’ve been a part of most of the decisions that have had impact.” The day earlier, she launched an unwise attack on Gov. Ron DeSantis (R-FL) for not taking her call as he prepared his state for a massive hurricane. The same day, Biden praised DeSantis for his good work. Not a good week on the tightrope.

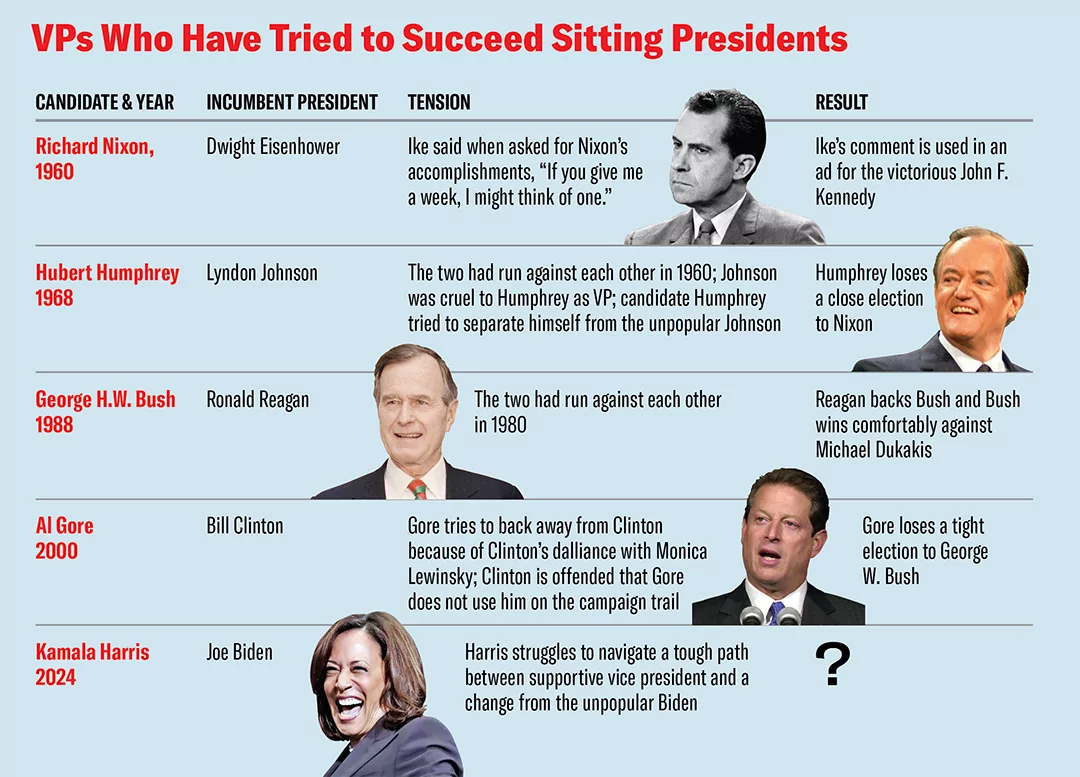

Harris is the fifth sitting vice president since 1960 to try to succeed a sitting president. In every one of those cases, there has been at least some tension between the candidate and the incumbent, usually steeped in underlying tensions that predated the vice president’s campaign for president. Clearly, this year is no different — and might be the most contentious of all.

In 1960, Vice President Richard Nixon sought to replace two-term incumbent and former Gen. Dwight Eisenhower. While Ike was popular with the people, he and Nixon had their problems. When Nixon came under fire in the 1952 campaign for alleged financial improprieties, Eisenhower let Nixon dangle in limbo, until Nixon rescued himself with a strong TV appearance that became known as the Checkers speech. Impressed, Eisenhower told Nixon, “Why, you’re my boy,” and kept Nixon on the victorious 1952 ticket. Even so, tension between the two men persisted. In 1956, Eisenhower offered Nixon a Cabinet slot, suggesting that this could give Nixon substantive experience to prepare for a run for president. Nixon, recognizing that this would be seen as a demotion, refused.

In 1960, when Nixon did run for president, Eisenhower was not much help. When asked about Nixon’s biggest accomplishments as vice president, he said, “If you give me a week, I might think of one.” Although not intended as an insult, John F. Kennedy’s team used the comment in a campaign ad. Nixon chose to limit Eisenhower’s campaign appearances on his behalf, a decision that annoyed Eisenhower. Nixon lost a close election to Kennedy in November, in part because of this lack of coordination between Eisenhower and Nixon.

In 1968, Lyndon Johnson’s vice president, Hubert Humphrey, ran against Nixon as he was vying for the White House again. Humphrey and Johnson had both sought the presidency in 1960 but lost out in the nomination quest to Kennedy.

Johnson and Humphrey had a tense relationship. When Johnson served as Kennedy‘s vice president, Johnson was frustrated by consistently demeaning treatment from Kennedy’s staff. Once Johnson became president, he could’ve chosen to treat his own vice president more kindly than he had been treated. Instead, he tormented Humphrey as if in revenge for the way he had been mistreated. He kept Humphrey out of the loop and unnecessarily made him wait around for meetings. The satirist Tom Lehrer even wrote a 1965 song about Humphrey’s plight:

Whatever became of Hubert?

Once a fiery liberal spirit, but now when he speaks he must clear it …

Did Lyndon, recalling when he was VP,

Say, “I’ll do unto you like they did unto me?”

When an embattled Johnson decided against running in 1968, Humphrey stepped into a “terrible box,” according to his campaign aide Ted Van Dyk. Johnson was not running again because of public dissatisfaction with the war in Vietnam. Humphrey had to find a way to remain loyal to the administration he was serving while also separating himself from Johnson and the war’s unpopularity. It didn’t work. This time, Nixon was on the winning side of a squeaker election.

It was 20 years before another sitting vice president tried to succeed the president he was serving. In 1988, George H.W. Bush sought to win the presidency, serving a “third term” for popular President Ronald Reagan. Bush and Reagan had a contentious history. As competing candidates in the 1980 Republican nomination contest, the younger Bush alienated Reagan and his staff by implying that the 68-year-old Reagan was too old to run for president. Reagan and Bush also clashed at the New Hampshire debate, when Bush tried to limit the number of candidates onstage, and Reagan, who had sponsored the event, wanted the debate open to the other candidates in the race. This led to Reagan‘s famous “I paid for this microphone, Mr. Breen,” comment, a signature moment that helped Reagan defeat Bush in New Hampshire and in the nominating contest overall.

Because of this history, nobody, including Bush, expected the victorious Reagan to choose Bush as his vice presidential pick. Nevertheless, after the effort to select former President Gerald Ford inevitably collapsed under its own weight, Reagan surprised Bush by asking him to join the ticket. Bush then surprised Reagan and the political world by being a consistently supportive vice president. When it came time for Bush to run in 1988, Reagan remained neutral in the Republican primaries but strongly supported Bush in the general election. There were some minor moments of tension, though. When Bush, in his 1988 Republican National Convention speech, pledged to strive for a “kinder, gentler nation,“ a peeved Nancy Reagan, recognizing the shot that had been taken at her husband, asked, “Kinder and gentler than what?“ This was a minor kerfuffle, though, and Reagan’s backing helped Bush comfortably defeat Democrat Michael Dukakis. The nation was endorsing Reagan‘s “third term.”

Bush was unable to get a fourth term for Reagan, though. He ran and lost to the Bill Clinton–Al Gore ticket in 1992. Unlike some of the other vice presidents who had run to succeed their president, Clinton and Gore had never run against each other. Gore ran for the Democratic nomination in 1988, losing out to Dukakis, and he chose not to join the field looking to defeat Bush in 1992.

While Clinton and Gore got along well initially, things got complicated in Clinton’s second term. Clinton’s inappropriate relationship with the young White House intern Monica Lewinsky roiled his presidency and led Gore to worry, understandably, that it could harm his own presidential bid. In his presidential campaign against George W. Bush, Gore intentionally ran away from Clinton. The standoffishness irked Clinton, who felt that his popularity and strong economic record would be an asset, not a liability, to Gore on the campaign trail.

When Gore lost an incredibly close collection to Bush, each man blamed the other in a tense White House meeting. Gore looked to Clinton’s sexual misbehavior, and Clinton was dismayed at not being deployed to Gore‘s advantage in a tight contest. Aides got involved in the tussle as well, including an anonymous Clinton adviser who said of the Gore team, “I don’t think the fact that they lost four out of four debates had anything to do with Bill Clinton.” The relationship between the two men never recovered.

As for Harris, she, like Humphrey and Bush, had run against the president she served. In that 2020 contest, she took the toughest shots against Biden, implying that he was a racist for opposing busing and being civil to some of his segregationist Senate colleagues while serving as a senator from Delaware. Her comments particularly angered Jill Biden and were seen as an impediment to Harris getting the vice presidential nod. But Joe Biden pledged to pick a woman as vice president, which later morphed into a pledge to pick a black woman, leaving Harris as the most vetted option.

As vice president, Harris reportedly alienated the Biden team with her staff tumult and staggeringly poor performance in interviews. But when Biden’s candidacy became nonviable after his disastrous debate performance against Donald Trump, Harris managed to emerge with the nomination but without having to go through the nomination process.

Now she must navigate the difficult path between her “I am not Joe Biden” comment, Biden’s claim that she has been “a major player in everything we’ve done,” and her comment that “there is not a thing that comes to mind” that she would’ve done differently from Biden. She also has to deal with the fact that policy positions associated with Biden, none of which she has disavowed, poll lower than the same positions when not associated with Biden.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

At the same time, Biden remains president and reportedly does not appreciate any indication that Harris wants to run away from Biden and his record. Harris, for her part, seems wary of offending Biden, even as Biden’s team grumbles that she does not highlight what Biden has done as president. She also pointedly has no plans to campaign with Biden on the trail, an avoidance of the sitting president strategy that did not work out well for Nixon in 1960 or Gore in 2000.

As this history shows, tension between a vice president and the president under whom they serve has generally corresponded to a close loss in a tough election. The Reagan-Bush counterexample shows that alignment between a vice president and president can foreshadow a comfortable election victory. Unfortunately for Harris, that approach worked because Reagan was popular, which Biden decidedly is not. Association with the Biden record presents a political problem for Harris, but drifting too far from him could signal trouble as well.

Washington Examiner contributing writer Tevi Troy is a senior fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center and a former senior White House aide. He is the author of five books on the presidency, including the new The Power and the Money: The Epic Clashes Between Commanders in Chief and Titans of Industry.