President Donald Trump has had a fondness for naming things long before he entered office.

As Trump the businessman, “Trump” itself became a global brand. He attached his name to everything from properties to games to vodka. In his business days, “Trump” denoted prestige and stability, with investors hoping that their attachment to as prominent a celebrity as Trump would serve as an additional booster to their fortunes.

For Trump the man, putting his name on companies and ventures asserted his ownership over them. This is a pattern that would naturally blend with a common historical phenomenon.

Throughout history, naming territory was one of the first steps taken in asserting ownership over an area. Alexander the Great, famously and allegedly, named 70 cities after himself — and one after his horse. During the colonial era, spanning from the 15th to the 20th centuries, European explorers would often rename locations, frequently after Christian figures or their rulers, to legitimize their conquests. Many of these names have endured into modernity, such as the Pacific island archipelago named in the 16th century after King Philip II of Spain, the Philippines, and the Central American country named after Jesus Christ, El Salvador.

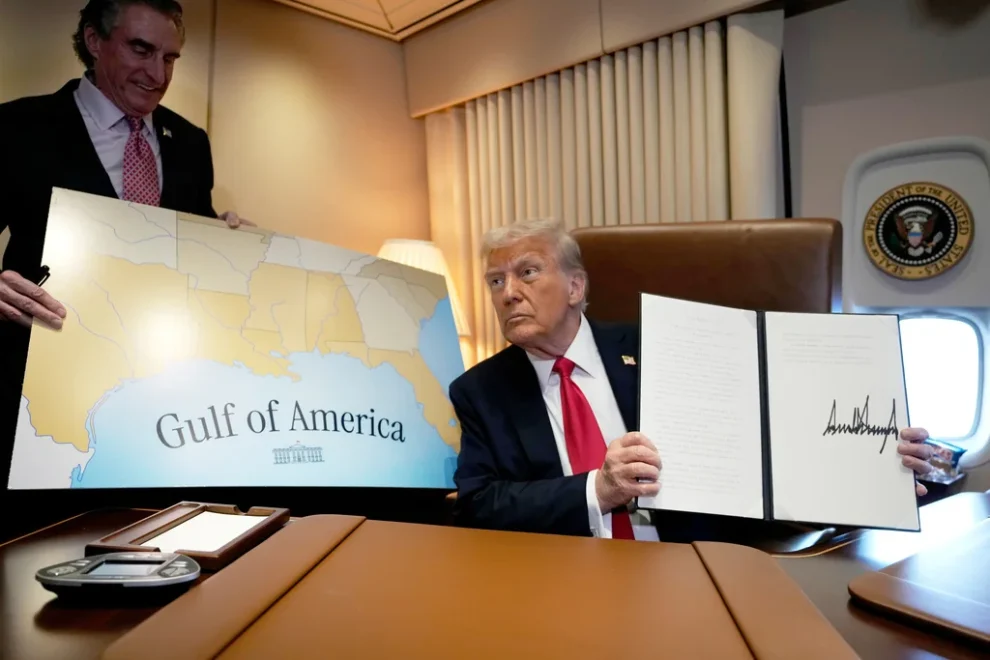

Trump’s most significant and controversial naming ventures reflect this theme, with a modern twist. The largest, renaming the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America, is intended to boost American pride and prestige and hint at the United States’s ability to assert control over the body of water.

“The Gulf will continue to play a pivotal role in shaping America’s future and the global economy, and in recognition of this flourishing economic resource and its critical importance to our Nation’s economy and its people, I am directing that it officially be renamed the Gulf of America,” the executive order renaming the Gulf read.

Names in politics are often used to make an argument. East Germany constructed the Berlin Wall to prevent its citizens from fleeing to the more prosperous West but sold the barrier to its populace by claiming that it was a defensive measure intended to keep out West German Nazis who were trying to infiltrate and undermine the socialist state. As such, the East German government officially called the wall the “Anti-Fascist Protection Rampart.” Citizens thereby voiced the government’s argument when addressing the giant barrier bisecting Berlin and identified themselves as being on the government’s side just by speaking it.

While a much less extreme example, the “Gulf of America” has much of the same effect: Those who identify the body of water with its new designation acknowledge American sovereignty over the Gulf and implicitly echo Trump’s nationalist stance. Likewise, Trump’s supporters have adopted the new name with glee, while his opponents continue using its previous name.

The renaming of domestic locations also occurs in a similar vein. For decades, left- and right-wing figures have battled over the names of streets, public landmarks, and more.

This battle has ample historical precedent, with dozens of African and Asian countries commemorating their independence from European colonial powers by renaming their countries and cities to reflect the local character, such as changing Rhodesia to Zimbabwe and the Dutch East Indies to Indonesia. Ukraine commemorated the Euromaidan by renaming numerous streets and cities, often changing the names from Red Army heroes of World War II to those of Ukrainian nationalist leaders.

In the U.S., the naming battle reflects differing conceptions of the nation’s history. Left-wing activists often seek name changes to reflect names given to places by the American Indians, or rename places that take their names from controversial American figures to civil rights activists. Right-wing activists are almost unanimously against such changes, arguing that they distort or weaken Americans’ conceptualization of themselves and their history. Trump falls decidedly in the latter camp, explaining his logic in the February executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico.

“It is in the national interest to promote the extraordinary heritage of our Nation and ensure future generations of American citizens celebrate the legacy of our American heroes,” the order read. “The naming of our national treasures, including breathtaking natural wonders and historic works of art, should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans in our Nation’s rich past.”

One of Trump’s first renaming moves in his second term was renaming the mountain with the highest peak in North America from the Indigenous Denali to Mount McKinley, named after one of Trump’s favorite presidents.

The renaming of the Gulf of America and Mount McKinley was seen as so important to Trump that he devoted time to it during his inaugural address.

“A short time from now, we are going to be changing the name of the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America,” Trump said. “And we will restore the name of a great president, William McKinley, to Mount McKinley, where it should be and where it belongs.”

He began a renaming blitz along these lines during his second administration, mainly targeting names deemed “woke.”

Among the most obvious targets was Black Lives Matter Plaza, situated in front of the White House, which itself was intended by Washington, D.C., as an obvious rebuke of Trump during the final year of his first term. Mayor Muriel Bowser quickly acquiesced to Trump’s threats after his allies in Congress threatened to strip the city of federal funding if the name wasn’t changed. The demise of the plaza was symbolically complete by March, when the large “BLACK LIVES MATTER” lettering was removed by construction crews.

A major initiative of the Biden administration was to remove the names of all military bases named after Confederate generals. The Trump administration reversed the moves, with Trump announcing in a June 10 speech to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the U.S. Army that seven former names would be reinstated.

“For a little breaking news, we are also going to be restoring the names to Fort Pickett, Fort Hood, Fort Gordon, Fort Rucker, Fort Polk, Fort A.P. Hill, and Fort Robert E. Lee,” he said.

The switch came with a twist; to avoid the previous controversy, most of the names would denote other war heroes who coincidentally had the same name. Fort Bragg, for instance, was named after Pvt. Roland Bragg, a paratrooper during World War II who served with distinction in the Battle of the Bulge.

DEMOCRATS’ POPULARITY FALLS FURTHER AS NEARLY TWO-THIRDS HOLD ‘UNFAVORABLE’ VIEW OF PARTY: POLL

The new names reflect Trump’s syncretic nationalism, holding dear to old traditions but with a modern spin. Some old-style conservatives were disappointed that the names weren’t specifically referring to their previous namesakes.

By spearheading the renaming efforts to, in his view, restore American pride and prestige, Trump is implicitly attaching himself to American identity. The longevity of these efforts will be tested after his second term ends.