Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing endangers fisheries across the globe that contribute to economic growth, food systems, and ecosystems, and the Trump administration is trying to crack down on violations in the Gulf. The Washington Examiner traveled to the South Padre Island and Air Station Corpus Christi to ride along with the Coast Guard during a boat patrol tour and take a daily overflight tour of the Deep Gulf. Installment two of In too deep: Illegal fishing in the Gulf — and the Coast Guard’s action plan explores how changes in Justice Department policy have led to greater enforcement of fishing restrictions.

The U.S. military and relevant law enforcement agencies have reported an initial dip in illegal fishing activities in the Gulf of America in recent months, after the Department of Justice began arresting and prosecuting individuals instead of releasing them back to Mexico.

The Coast Guard is among several agencies that work to ensure non-American fishermen don’t operate within the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone. Mexican fishermen will illegally fish in U.S. waters and try to make it back to Mexican waters before getting caught. If they pull that off, they will sell the fish — sometimes into U.S. markets — and the Gulf Cartel gets a cut of the proceeds, according to the Treasury Department.

The Gulf Cartel relies “on a variety of illicit schemes like [illegal, unreported, and unregulated] (IUU) fishing to fund their operations, along with narcotics trafficking and human smuggling,” former acting Undersecretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence Bradley T. Smith said last year, when the Treasury Department announced it was sanctioning five individuals with ties to the cartel.

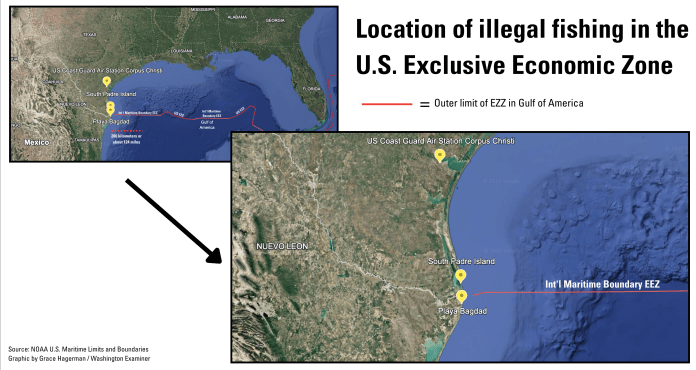

The western part of the Gulf of America is split between the U.S. and Mexican EEZs. Mexican fishermen will leave Playa Bagdad, a town where the cartel operates near the border, on “lanchas,” the name given to the small, single-engine boats they use, and sail into the U.S. EEZ.

The U.S. effort to stop Mexican fishermen from fishing in U.S. waters has several components.

U.S. Coast Guard Station South Padre Island is only 6 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border and is one of the primary entities that would be involved in the physical interdiction of these vessels. It works alongside Customs and Border Protection Air and Marine Operations, as well as with Coast Guard Air Station Corpus Christi, which provides air support for those operations, and other outposts along the Gulf.

The guard members at South Padre Island carried out 31 interdictions during the calendar year 2024, seizing 6,690 pounds of fish, while they have only carried out 15 this year, which resulted in the seizure of 4,601 pounds of fish, according to a guard spokesperson.

The primary change from last year to this year was the decision by federal officials to begin charging these fishermen under the Lacey Act, which prohibits the trafficking of illegally acquired wildlife, fish, or plants. Previously, the Coast Guard would release the fishermen back to Mexico.

Lt. Ryan Sexton, commanding officer of U.S. Coast Guard Station South Padre Island, told the Washington Examiner that they would frequently detain the same individuals.

“Oftentimes when we do interdictions, it’s not the first time that we see somebody,” he added, noting that in some cases they’ve been caught illegally fishing “30-40 times.”

Sexton said a common sentiment of service members at South Padre Island was that by the time they were “done [with] the case package” related to an interdiction, “that same person would be back because they were interdicted a second time.”

In the DOJ’s first prosecution of Mexican fishermen illegally fishing in U.S. waters, four members of a fishing crew pleaded guilty in June to knowingly transporting nearly 700 pounds of red snapper with an estimated value of more than $9,000.

“The arrest and prosecution of Mexican commercial fishermen marks a change in policy concerning the protection of U.S. marine resources. In past instances, authorities would seize the catch and destroy the vessel but release violators back to Mexico,” a release from the DOJ said. “Any commercial fisherman now apprehended in U.S. waters caught violating the Lacey Act face potential fines and imprisonment.”

QUARTER-MILLION AMERICANS HAVE APPLIED TO ICE AND BORDER PATROL UNDER TRUMP

Miguel Angel Ramirez-Vidal, the captain of the boat, had been arrested on 28 prior occasions for illegal fishing, according to the U.S. attorney’s office in the southern district of Texas. The other three aboard the lancha had “similar previous arrests,” according to a press release from the attorney’s office.

Ramirez-Vidal was ultimately sentenced to eight months in jail for his most recent offense.

Sexton said the decision to charge these fishermen “made an impact on the morale” of the Coast Guard officers as well, “because they’re seeing that the [perpetrators of] illicit activity that’s going on being held accountable for it, and that’s huge.”

The threat of prosecution, he said, has served as a newfound deterrence to the Mexican fishermen.

Lt. Carl Weaver, a Coast Guard copilot stationed at Coast Guard Air Station Corpus Christi, agreed with Sexton’s assessment that interdictions have gone down in recent months following the decision to start charging those fishermen.

The guardsmen at Air Station Corpus Christi are part of the multifaceted effort to stop these illegal fishermen. Flying above the Gulf, they have more visibility than a Coast Guard vessel on the water and can guide vessels to the fishermen’s location.

The Washington Examiner went on a boat patrol ride-along with the Coast Guard out of South Padre Island and an overflight with Air Station Corpus Christi and did not encounter illegal fishermen on either one.

The increased punishment for Mexican fishermen caught illegally fishing in U.S. waters — who sometimes will also smuggle drugs — is a part of the Trump administration’s larger strategy to clamp down on drug smuggling and illegal entry into the country via the southern border by land and water.

Early on, the Trump administration suspended the admission of immigrants at the southern border, declared an emergency, halted refugee admissions, returned to holding asylum-seekers in Mexico, put a stop to “catch and release” policies, and implemented more robust military participation.

In February, the Washington Examiner spent several hours with U.S. Border Patrol near the Rio Grande on a predawn to late morning ride-along, but did not see anyone attempting to cross the border — a first in the 60 trips the reporter has taken to the border.

BORDER PATROL ARRESTS OF ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS OVER PAST YEAR HIT 55-YEAR LOW

More recently, the U.S. military has begun conducting lethal strikes against boats the administration has said originated from Venezuela and were carrying drugs intended for the United States. In the handful of reported instances, the U.S. military is believed to have killed more than two dozen people. The Department of War has not shared evidence that drugs were on the vessels they struck or who was killed in the strikes.

These strikes are a part of the administration’s effort to pressure Venezuelan President Nicolas Máduro, who has held on to power via elections widely believed to have been shams. He is wanted by the FBI for his alleged ties to a cartel operating in Venezuela.

“Maduro helped manage and ultimately lead the Cartel of the Suns, a Venezuelan drug-trafficking organization comprised of high-ranking Venezuelan officials,” the State Department reports. “As he gained power in Venezuela, Maduro participated in a corrupt and violent narco-terrorism conspiracy with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a designated Foreign Terrorist Organization.”

U.S. Southern Command announced the establishment of a new Joint Task Force under II Marine Expeditionary Force to lead counter-narcotics efforts across the Western Hemisphere earlier this month.

A strike last week was the first in which there were any survivors. The military saved the two survivors of the strike but has chosen not to charge them under U.S. law, and instead has handed them over to their home countries, Colombia and Ecuador. The decision raised eyebrows, considering the administration’s adamant stance that the U.S. is in an “armed conflict” with the cartels.

A recent U.S. strike occurred in the eastern Pacific, whereas the rest had taken place in the Caribbean Sea, and Trump said he’s approved CIA operations in Venezuela as well.