Former President Ronald Reagan had been out of office for five years when he returned to Washington, D.C., to address a Republican National Committee fundraiser. It was three days before his 83rd birthday. Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, RNC Chairman Haley Barbour, and Senate Republican Leader Bob Dole were among those on hand for the tribute and $1,000-a-plate dinner.

When the tuxedo-clad Reagan stepped up to the podium, he faltered a bit. He seemed out of sorts and unsure of himself. It was only temporary, however. Reagan launched into his speech in earnest, taking shots at then-President Bill Clinton, telling stories, and cracking jokes as normal. He went on for over 20 minutes, and the event was a success.

Nancy Reagan never let him give a live speech in public again. (There were some subsequent videotaped remarks.) Later that year, the former president wrote a letter to the public informing them of his Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis.

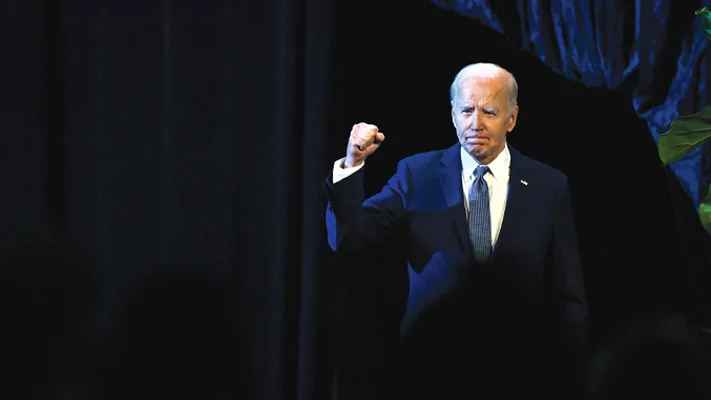

It’s probably too soon for first lady Jill Biden to wish she had similarly encouraged her husband’s gracious exit from the public square. No grim medical diagnosis is necessary, though many self-appointed internet physicians have stepped in to offer them, to realize that President Joe Biden has, at 81, become a diminished communicator at the precise moment his party most needed him to excel in that role.

The president is nowhere near as good extemporaneously as he was for most of his 50-plus years in politics. Since rallying to deliver what is now sure to be his last State of the Union address earlier this year, Biden has slipped noticeably in his ability to read reliably from a teleprompter. His voice sounds weak. He loses his train of thought. He confuses names he ought to remember.

Biden reached his nadir on June 27 in the most lopsided debate in the history of presidential debates. It was an encounter his campaign had requested, subject to ground rules his aides had devised to be helpful to him. The exchange was nevertheless a disaster from which his reelection campaign never recovered. After three weeks of attempted intransigence, Biden succumbed to his own party’s demands that he exit the race.

It was a stunning fall from grace for a two-term vice president who finally won the presidency on his third attempt after 33 years of trying, not counting the 2016 race he was dissuaded, again by his own party and then boss, from entering in the first place. In an Oval Office address explaining his decision to reverse course several days after dropping out via social media and then not being seen in public for a while, Biden didn’t put it quite like this.

Instead, Biden appealed to high-minded principles. “I revere this office, but I love my country more,” he said. “It has been the honor of my life to serve as your president, but in the defense of democracy, which is at stake, I think is more important than any title.”

“America is going to have to choose between moving forward or backward,” Biden continued. “Between hope and hate. Between unity and division. We have to decide, do we still believe in honesty, decency, respect? Freedom, justice, and democracy?”

These are the contradictions Biden has never been able to resolve, not in his single term as president or in his lengthy career in Washington. He speaks on the one hand of unity, decency, respect, and democracy, of treating political rivals as friends and neighbors. Yet on the other hand, he frames his political opponents as the forces of darkness and existential threats to the constitutional system of government.

Perhaps this was understandable in the context of when Biden took office, 14 days after the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol by supporters of former President Donald Trump who did not wish to accept and hoped to overturn the 2020 election results. But Biden has always vacillated between invoking bipartisanship and throwing sharp partisan elbows, emphasizing civility while attacking his opponents in the crassest political terms.

Some of this is the culture of the Senate, where Biden served for 36 years. You excoriate fellow members and their policies in speeches on the chamber’s floor while addressing them as “my friend.” Senators can be friendly in private while sharply critical of each other in public, a practice that was even more common when Biden was in his prime. But as vice president, Biden hinted to a black audience that Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan were going to enslave them if they won the 2012 election. He has denounced as fascistic and “ultra-MAGA” policy positions on abortion that he once held himself.

Fighting for his own political life, Biden could not figure out how to strike the civil and unifying tone he called for the rest of the country to adopt in the wake of the assassination attempt on Trump. Days after dropping out, Biden released a statement about the now-former Secret Service head who presided over that grave security failure that politely thanked her for her service after lawmakers of both parties angrily demanded her resignation.

Biden stood by as Democratic prosecutors and officials tested legal and constitutional theories as novel as anything John Eastman concocted to disqualify, bankrupt, and possibly incarcerate Trump, giving a speech at the White House to complain that the Supreme Court made it difficult to put the Republican presidential nominee on another trial before the election. The president has frequently attacked the high court saying his version of “Supreme Court reform” is also “critical to our democracy.”

It is Biden’s defense of democracy, which he planned against the advice of unaffiliated Democratic operatives to make the centerpiece of his abortive reelection campaign, that looks most contradictory with the sad conclusion of his public life.

Biden entered the Democratic primaries as allies dissuaded other candidates from doing so, fearing a competitive process would weaken him in the general election. He won them against token but at least sentient opposition, receiving 14 million votes. When he initially resisted calls to withdraw after his disastrous debate, he cited these voters, “not the press, not the pundits, not the big donors, not any selected group of individuals, no matter how well intentioned,” as the rightful decision-makers.

After being presented with polling data that suggested Biden might lose a democratic general election to his opponent, Biden acceded to the wishes of the press, pundits, donors, and a “selected group” of influential Democrats — the most important of whom, Barack Obama and Nancy Pelosi, had ostensibly surrendered their leadership positions to other people, though at least Pelosi remains an elected member of Congress — and bowed out before he could even be seen in public.

Biden then threw his support behind Vice President Kamala Harris, who has never won a single Democratic (or democratic) primary dating back to 2020, in a process that looks as closed as the abandoned primaries in which he alone among major candidates participated. Within 36 hours, she was crowned the new presumptive nominee. She is at least an elected vice president, albeit in another election cycle with Biden at the top of the ticket.

There is an argument that political parties are private organizations that are not obligated to pick their nominees democratically. Great presidents have been chosen by their parties less democratically. Parties are supposed to identify candidates who can win. That is not the process most Democrats have believed they were following since 1972, the year Biden was first elected to the Senate. More importantly, this argument is difficult to square with the contention that the Electoral College, the filibuster, and the composition of the Senate itself are undemocratic and therefore illegitimate. The principle is either one person, one vote, or it is not.

It is abundantly clear that Democrats often use democracy as a cudgel with which to beat their opponents. When Democrats could win majorities of the size that enacted legislation ranging from the New Deal to Obamacare, they accepted the legitimacy of the system. Once they could no longer win majorities that large, they wanted everything to be done with 50% plus one — one time.

Biden, the victim of what a former spokesman to the first lady described to Fox News as a “political intervention of epic proportions,” has played an outsize role in all this. Indeed, stories that came out in the attempt to end his reelection bid raise important questions about how engaged he, as the elected president, ever was in the day-to-day process of governing.

The Wall Street Journal reported as Biden lost his grip on the Democratic nomination in July that during his first year in office, he had “spoken disjointedly and failed to make a concrete ask of lawmakers” in a meeting with House Democrats, prompting “a visibly frustrated” Pelosi to intervene and explain what was needed. “That was October 2021,” the report noted. “That month was the last time Biden met with the House Democratic caucus on the Hill regarding legislation.” (The White House denied covering for Biden’s infirmities on the same day he publicly explained his rationale for leaving the presidential race.)

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

When it looked like Biden was going to lose an election rather than just the attention of Democratic lawmakers, Pelosi took more than the microphone away from him.

Democrats are grateful Biden finally passed the torch. If democracy does not go their way in November, we can expect to hear more stories about what his term was really like.

W. James Antle III is executive editor of the Washington Examiner magazine.