The Empire Strikes Back famously features a string of Imperial officers being summarily executed by Darth Vader as their horrified successors look on with concern. The lesson? Sometimes, one climbs the ladder only to fall from a greater height.

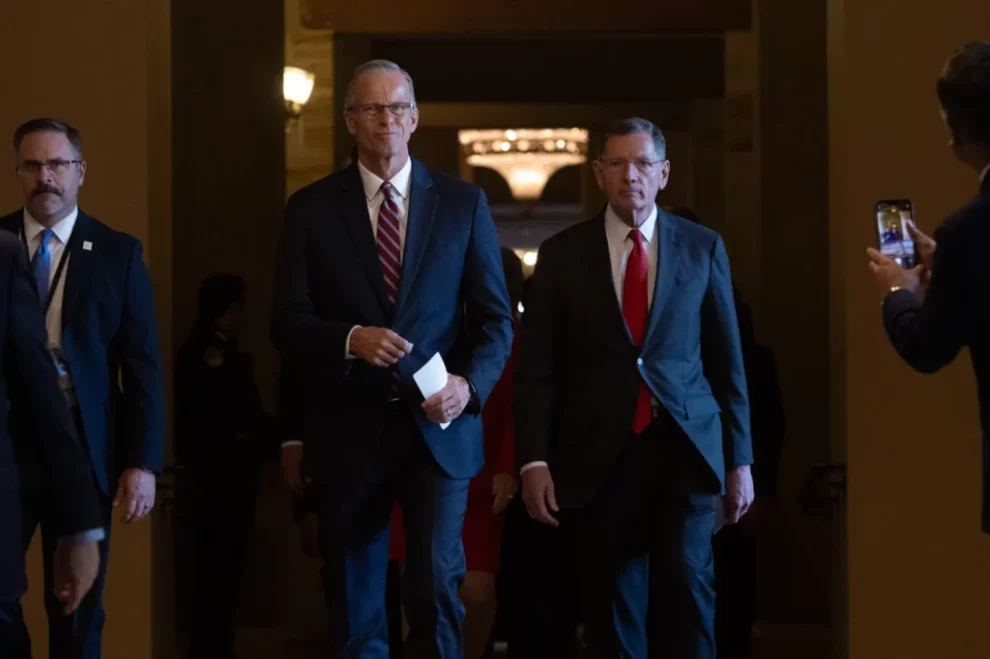

Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD), the man who has succeeded Mitch McConnell as the Republicans’ leader in the world’s greatest deliberative body, has shown no signs of harboring similar reservations about assuming his new responsibilities, even though the associated risks are abundant.

McConnell leaves his watch as one of the most accomplished and consequential conservative figures in American history. Alongside once and future President Donald Trump, McConnell remade the Supreme Court and larger federal judiciary.

That effort yielded more than bragging rights. Roe v. Wade has been consigned to the trash heap of history. The power of both the president and the unelected bureaucracy in his branch has been curbed. People enjoy stronger First and Second Amendment rights than their forebears at a time when progressives are more determined than ever to take them away.

Victory after victory for constitutional conservatives has been achieved by the judiciary — and McConnell. None of them might have been won were it not for his decision to hold open the seat left vacant when Justice Antonin Scalia died in 2016. Or his expert navigation of the fraught confirmation processes that saw Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett elevated.

His reward for those efforts is not only the scorn of the Left but also his own party, which widely regards him as an obstacle to success, if not an outright traitor to the cause.

And while the outlines of the image of McConnell, squish, were drawn during the Tea Party era, it was Trump who colored them in.

As early as the first year of his presidency, Trump began lobbing attacks at the senior senator from Kentucky, suggesting he might need to be replaced and savaging him for failing to get a slim Republican majority to repeal and replace Obamacare with a wildly unpopular bill. Those attacks took on a new and more vicious tenor, however, after McConnell refused to be complicit in Trump’s efforts to hold on to power after his defeat to Joe Biden in the 2020 election.

In February 2021, Trump released a two-page statement that led with the claim, “The Republican Party can never again be respected or strong with political ‘leaders’ like Sen. Mitch McConnell at its helm” and concluded by calling him “a dour, sullen, and unsmiling political hack.”

The rhetoric only escalated from there. In the fall of 2022, Trump accused McConnell of championing “Trillions of Dollars worth of Democrat sponsored Bills” and risibly suggested that “he believes in the Fake and Highly Destructive Green New Deal, and is willing to take the Country down with him.”

“He has a DEATH WISH,” Trump added. “Must immediately seek help and advise [sic] from his China Loving wife, Coco Chow!”

It was just one of many times that Trump would invoke the Taiwanese heritage of McConnell’s wife, Trump Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao, against the couple.

Of course, Trump isn’t the only force rendering Thune’s promotion as daunting as it is promising.

As Americans’ conception of politics has transformed from a means of preserving liberty and promoting the general welfare into a ceaseless, dirty war between red and blue, so too has their understanding of the roles of the three branches of government and their denizens.

“But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department [branch] consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others,” Federalist 51 reads. “The provision for defense must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

In other words, the Constitution is designed to facilitate a form of government in which all three branches jealously cling to the powers reserved for them and safeguard them from the others’ ambitions.

That is decidedly not the state of affairs today. In the United States’s highly partisan, nationalized atmosphere, members of the two political branches, the legislative and executive, are mostly beholden not to the institutional interests of the bodies they comprise but interest groups within their own parties that threaten their job security.

One pernicious consequence of this development is that the branches tend to check one another only if they’re controlled by the opposite party. Moreover, individual lawmakers in Congress, which is meant to be by far the most powerful branch, are actually incentivized to give away their institutional power to the other two for fear of taking a hard vote that could prove dangerous in a primary or general election. Hence the imperial presidency and long-standing reliance on the Supreme Court for sweeping pronouncements on controversial issues such as abortion.

Trump’s emergence on the scene has had a kind of force multiplier effect on these trends. His personal hold on a large percentage of the Republican electorate and eagerness to involve himself in primaries has yielded a class of politicians that conceives, or at least that says it conceives, of its role as supporting a fickle man’s whims.

If the spirit of the framers’ vision for separation of powers survives anywhere in the political branches, though, it’s the Senate. The filibuster, the well-developed constituencies of its members, and the six-year terms they serve insulate members of the upper chamber somewhat from pressure applied by the executive branch.

The Senate’s closer adherence to that vision, however, does not mean that Trump and his constituency will cut it any more breaks should it defy him. That makes Thune one of the defining figures of the second Trump term.

There is, of course, an extent to which any Republican leader in the Senate is bound to disappoint Trump. Unlike the House, where the speaker and his counterpart in the minority exercise quite a bit of influence over their caucus, Senate leadership is more limited in its ability to sway colleagues.

Even McConnell, who was unusually effective at the peak of his powers, could do nothing to compel John McCain, a war hero and former GOP presidential nominee in his sixth term, to vote to do away with Obamacare without the right replacement bill teed up.

But it’s also true that McConnell was the closest thing to a foil Trump could have had. While the man referred to by his enemies on the Left as Nuclear Mitch might have a well-earned reputation as a ruthless partisan strategist, McConnell remains one of only a few true institutionalists who believe Congress to be indispensable rather than just a means to an end. Similarly, he believed his mandate as leader to be to advance his caucus’s interests rather than the president’s.

That’s why he rebuffed Trump’s calls for him to do away with the filibuster. And, paradoxically, that’s also why he ended up voting to acquit Trump in his second impeachment trial following the Jan. 6 Capitol riot. Despite his horror at the events of the day, McConnell knew that if he voted to convict and pressured his Republican colleagues to do the same, it would focus Trump’s ire on them.

To the end, McConnell understood his job to be serving those who gave him it, rather than Trump. And he took the arrows, be they from the Left or the Right, that came as a result.

Thune has already taken a few arrows of his own.

Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) ran for the top leadership job on a platform of acquiescing completely to Trump. The president-elect himself kept his powder dry and lent Scott no endorsement, but some of his most prominent allies, including Tucker Carlson, Elon Musk, and Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA), all loudly proclaimed that Scott was the man for the job. Musk called Thune “the top choice of Democrats.”

Scott came in a distant third in a secret ballot. Thune prevailed with relative ease. But his time working alongside Trump is just beginning. Thune is owed fewer debts from his colleagues than McConnell was by the time he found himself at odds with Trump.

Still, there are reasons for optimism.

A polished communicator who once considered running for president, Thune carries almost none of the baggage that made McConnell an easy target for Trump. But he also spent years as the Kentuckian’s protege, learning all of the tricks of the trade that made him so effective. If Thune turns out to have mastered half as much as his mentor, he’ll be arguably better positioned for success than his predecessor ever was.

Moreover, Thune, having only just ascended to his position, will be much more motivated than McConnell ever was to work with and accommodate Trump. In remarks delivered immediately following his elevation, Thune promised to deliver not just Republican or conservative priorities but “President Trump’s priorities.” Regardless of how he intends to act, that’s the kind of rhetorical choice that will endear you to the president-elect.

Thune threw Trumpworld another bone just a couple of days later when he suggested that “all options are on the table, including recess appointments” for the most controversial of Trump’s nominees, including Director of National Intelligence-designate Tulsi Gabbard and Health and Human Services Secretary-designate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. An unconstitutional recess-appointment scheme of the kind that has been floated by the Trump transition team would be self-evidently destructive. McConnell already came out against it.

Perhaps Thune’s wink at something that is unlikely to come down the pike, though, is a sign of a political savvy that could keep him in Trump’s good graces — and in his new position — over the next four years.

Also working in Thune’s favor is the composition of his conference. Trump may have romped through the Republican primary in 2016, but even after he took office, many GOP senators remained skeptical of, if not outright hostile to, him. In 2017, McCain, Jeff Flake, Rob Portman, Pat Toomey, Ben Sasse, and Bob Corker all held office. In 2018, Mitt Romney won election to the Senate in Utah. With Romney’s retirement, that whole contingent is gone.

Those names have been replaced by the likes of Bernie Moreno, Dave McCormick, Pete Ricketts, Marsha Blackburn, and Bill Hagerty, all of whom are much less likely to oppose the Trump agenda than their forebears.

So, while Trump’s vicelike grip on the party today might increase the risk of Thune being in conflict with Trump at some point, it also insulates him from that risk.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Thune’s job is to balance the interests of his institution, his caucus, and a president unlike any other.

If he strikes the right one, he has an opportunity to leave a legacy every bit as rich as McConnell’s — even if the nature of his vocation is such that he is bound to be maligned for it.

Isaac Schorr is a staff writer at Mediaite and a Robert Novak fellow at the Fund for American Studies.