In 1816, John Keats wrote in his poem “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” that when he encountered George Chapman’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey, it filled him with limitless excitement. As he put it, “Then felt I like some watcher of the skies/When a new planet swims into his ken.” It is, unfortunately, more likely that when a high school student is presented with a copy of a similarly lauded literary masterpiece, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, they will not share Keats’s sense of giddy thrill but will instead complain.

The Great Gatsby is possibly the great American novel. And, although blessedly short at a mere 180 pages, it carries the usual imprimatur of classic literature regularly assigned as homework, namely that it’s boring. Many teenagers have yawned through their studies of Fitzgerald’s novel, unimpressed by its jazz age setting, brilliant evocation of romantic and sexual obsession, and the luxurious richness of its prose.

Although Baz Luhrmann’s 2013 movie adaptation of the book briefly made it fashionable again to a younger, hipper audience — the combination of Leonardo DiCaprio as Jay Gatsby, Jay-Z as soundtrack producer, and Lana Del Rey’s drawling in her customary somnambulant fashion about being young and beautiful was a potent one — it reaches its centenary this month as a fossilized relic of a long-gone era. It appears to say nothing to today’s youth about their experiences or lives. The America of The Great Gatsby is long gone, just as distant as the country found in Moby-Dick, The Scarlet Letter, or Little Women. Why should anyone want to bother reading it for pure entertainment?

My answer, predictably enough, is that The Great Gatsby is not simply some chore to be endured at a formative point in education, but one of those rare books that can be appreciated, even loved, at every point in its readers’ lives. Granted, perhaps those in grade school may be a little young to appreciate its linguistic and thematic complexities, but there is nothing in Fitzgerald’s prose, which is witty, stiletto-sharp, and clear as a pane of glass — that is more challenging than might be read in the average Substack. And in its peerless recreation of a world that perhaps never truly existed, even at the time that Fitzgerald was writing, it offers a thrill of discovery that even the most expensive fantasy novels and cinema cannot hope to equal. You can leave your Marvel pictures with their explosions, super-suits, and cheap one-liners. The truer explanation of what drives people to behave as they do was expressed quite brilliantly in 1925.

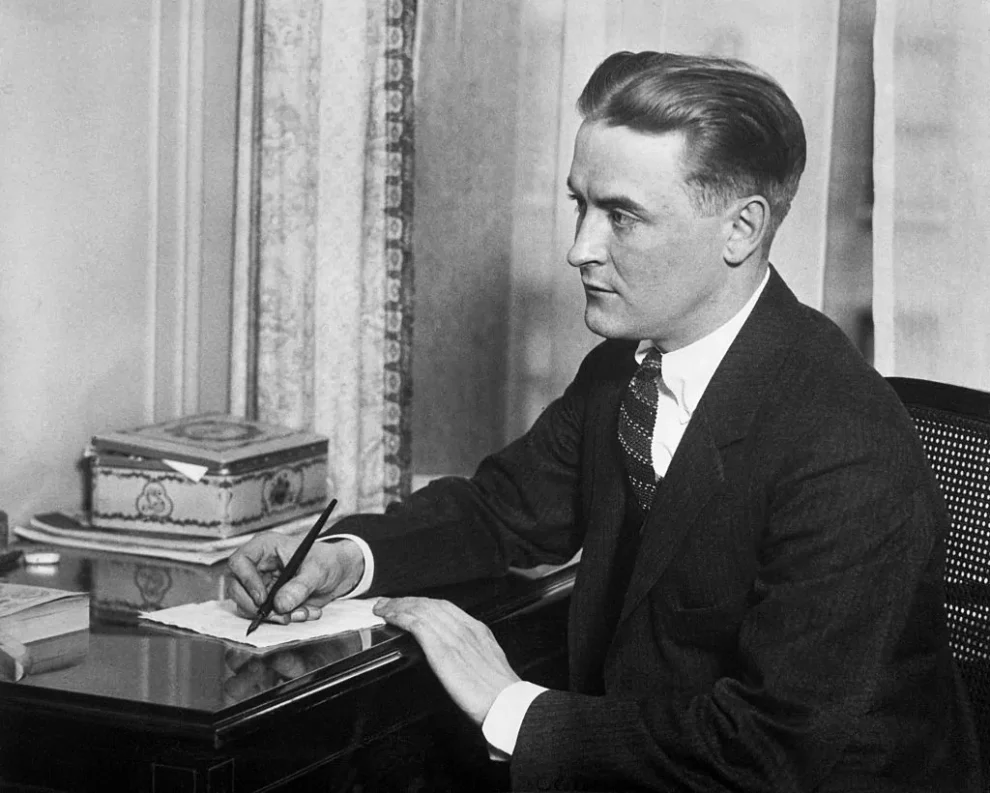

Stories about The Great Gatsby’s creation, publication, and afterlife have become legendary. How Fitzgerald based the character of the spoilt, insipid trophy girl Daisy Buchanan on the socialite Ginevra King, who he was not allowed to marry because he lacked prospects. How the novel’s original title, Trimalchio in West Egg, which the editor, Maxwell Perkins, told Fitzgerald readers would find obscure, was replaced with the teasingly ambiguous name it now enjoys, despite the author’s last-ditch attempt to call it Under the Red, White and Blue. How Fitzgerald’s hopes that it would be a commercial success were dashed, as it sold less than 20,000 copies. How he was frustrated by its critical reception — he declared, “Of all the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one had the slightest idea what the book was about.” How it only became a commercial hit after Fitzgerald’s premature death from a heart attack at the age of 44. And, perhaps most cruelly, how today, the self-appointed Fitzgerald cognoscenti scorn it as overrated, ostentatiously preferring Tender Is The Night, which they describe as his true masterpiece.

All these stories are true. However, just as the revelation that the louche millionaire Gatsby is really a bootlegger named Jimmy Gatz says everything and nothing about his character, they cannot wholly explain the enduring appeal of this novel. In a way, it is a shame that the novel was rediscovered relatively swiftly after Fitzgerald’s death when it was handed out as a mass-produced armed services edition in early 1942. The doomed Gatsby and his equally ill-fated creator became tied together in the public imagination. Fitzgerald, the bow-tie sporting, epigram-spouting, hard-drinking author par excellence, came to be posthumously regarded as the alter ego of his character. “The Great Fitzgerald” had a certain ring to it. That he was dead and could, therefore, be celebrated without embarrassment made the narrative considerably better.

The reason why Tender Is the Night is regarded by the snobs (sorry, cognoscenti) as a greater novel is not because it is better written or more psychologically acute, but because it is not being rammed down the throats of reluctant students year in, year out. Aspects of The Great Gatsby have become so well-worn as to be cliché. The final line — “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past” — and Gatsby’s continual, tic-like repetition of the term “old sport” are particular offenders in this regard. However, the iconography of the green light that dominates the characters’ hopes and dreams is just as well-worn. I pity any student (or journalist or college grad) who has to write on that most hoary of topics, “Was Gatsby truly great?”

Still, just because something is well-known does not mean it should be ignored. After all, no theater has shied away from producing Hamlet over the past four centuries. The enduring appeal of The Great Gatsby lies in its strange lacunae and darting alleyways. We remember Gatsby and Daisy and the novel’s narrator, the likable but ineffectual Nick Carraway, but there are enduring supporting characters, too. We revel in the gangster Meyer Wolfsheim, the white supremacist bully Tom Buchanan, and the sardonic golfer Jordan Baker, all of who come to vibrant life in the few pages that they show up for. It is a book of characters — indelible, flawed human beings who stand out as real people rather than place-holder stereotypes.

There are many novels that have suffered a similar fate of over-exposure to readers at too young an age. The Catcher In The Rye, Of Mice and Men, and The Old Men and the Sea have all faced the same problem of being associated with Gradgrindian forms of education rather than any genuine edification. Many thousands of students have grown up detesting rather than loving The Great Gatsby, having been compelled to read it by rote rather than coming to it of their own accord. However, in its centenary year, these once-averse and reluctant readers should be able to return to the novel once again and view it not as a punishment but as a privilege. It’s more likely than not that many of them — perhaps the ones who complained most vociferously at the time — will now thrill to a superlative book rather than regard its consumption as an ordeal. And therein lies the true greatness of The Great Gatsby, borne ceaselessly into the future.

Alexander Larman is the author of, most recently, The Windsors at War and an editor at Spectator World.