Summer’s here, and the time is wrong for voting in the booths. The personal ratings of British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and French President Emmanuel Macron have never been lower. The British and French economies are feeble, and Sunak and Macron’s parties are deeply unpopular with their publics. Yet both leaders have called snap elections in an attempt to head off challengers to their right. In both Britain and France, a centrist has set his party on the path to electoral destruction by popular demand.

Judging from the polls, the same might be said of President Joe Biden and the Democratic Party’s prospects in November. The electoral rhythm runs at different speeds in different nations, and the voters may punch upward with their left or their right, but the melody is much the same across the West. The people are running out of hope, but they still want change.

at a news conference in Paris, June 12, 2024. (Henry Nicholls/Getty Images) (Nathan Laine/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Macron, who won the French presidency in 2017, was the first major leader to come to power in the West after the double shock of Brexit and the Trump presidency. Sunak looks like the last, at least for now, in a sequence of supposedly steadying technocratic hands that, when it came to governing, showed an uncertain touch: Macron 2017, Biden 2020, Scholz 2021, Sunak 2022. Macron, now in his second term as president, cannot run again in France’s 2027 presidential elections. Biden, now in his second childhood, should not have run in 2020, let alone in 2024. Sunak will not get a second chance as Britain’s first minister and will be out of a job on election night.

Olaf Scholz can delay the next German federal election until October 2025, but the center-right opposition is polling twice as high as his Social Democratic Party, and his supporters in a “traffic light” coalition (yellow for the liberals, green for the Greens) are also diving in the polls. The prospects look similarly bleak for a cadet member of the centrist technocracy such as Justin Trudeau of Canada. Trudeau also has until October 2025, by which time he would be the longest-serving prime minister in Canadian history. His Liberal Party has sunk to just over 20% in the polls and is as much as 20% behind the Conservatives.

Over the next year or so, the political leadership of the West may well change entirely — and in ways far more drastic than that of 2016, the populist Year Zero.

Sunak in Pottery Barn

Sunak also could have waited. He had another six months before electoral law would have forced him to be scourged by public opinion. Prime ministers traditionally call elections at a propitious time, so on the face of it, Sunak’s decision was baffling. (“Doomed on the Fourth of July: A reckoning is coming for the U.K.’s Conservative Party,” May 30). There is talk in London that he jumped before he was pushed out by his increasingly desperate members of Parliament or that he is jumping ship because he would prefer to be living it up in Silicon Valley than grubbing for votes in the Thames Valley.

What Sunak has confirmed in the weeks since he called the election on May 22 is that he has no talent for electoral politics. Sunak is a financial wonk, not a democratic politician. He has a cool head, not a warm handshake. Obama’s brain, minus Obama’s charisma. When Sunak consulted his mental spreadsheet in mid-May, he saw good news. Inflation is coming down toward his target of 2%. The British economy is out of recession. These mild improvements had allowed the government to add a small cut in payroll taxation to its spring budget. They even suggest, if you’re a spreadsheet kind of guy, that the Conservatives can be trusted to fix the economy that they have broken.

The voters are past caring about marginal gains here and there. Taxes are at their highest since 1948. The debt-to-GDP ratio is edging toward a fatal equality that will undermine the markets’ confidence and send the pound down toward parity with the U.S. dollar. Sunak was former Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s chancellor of the exchequer during the coronavirus pandemic. He pushed taxes up and spending skyward. He is about to receive a lesson in what Colin Powell called the Pottery Barn rule. Sunak broke the economy, and now he owns it.

What the voters do care about is immigration. In 1997, when Tony Blair’s New Labour took office, the United Kingdom’s Office for National Statistics assessed immigration at 327,000 and net migration at 48,000. In 2010, when Blair successor Gordon Brown lost the general elections to David Cameron’s Conservatives, immigration was 604,000 and net migration 268,000. In the year to March 2020, under the Conservative government in which Sunak was serving, 715,000 people immigrated legally into the U.K.

The Blair government boosted immigration because the numbers boosted GDP — and because, as the New Labour speechwriter Andrew Neather admitted in 2009, changing the face of the country was a chance to “rub the Right’s nose in diversity and render their arguments out of date.” The election promises of every Conservative leader since 2010 included reducing immigration to “tens of thousands,” but the Conservatives kept admitting new immigrants at the same rate as Labour. They failed to honor their promises on immigration, then rubbed their voters’ noses in metropolitan liberalism. (“Promises, promises: Britain’s voters will punish Conservatives for breaking their word,” March 21) They are now merely a different flavor of Labour. As any change is better than none, the voters will punish the Conservatives on July 4 by giving Labour a landslide victory. The same vengeful spirit is driving even centrist voters back toward former President Donald Trump.

Powell’s rocket

Trump is in many ways the fulfillment of the prophecies of Pat Buchanan, much to mainstream Republicans’ discomfort. The U.K. Conservatives face a similar reckoning with a suppressed aspect of their own past. The implications are similar for the liberal conservatives who are the British equivalent of the Mitt Romney and Never Trump tendencies: electoral extinction.

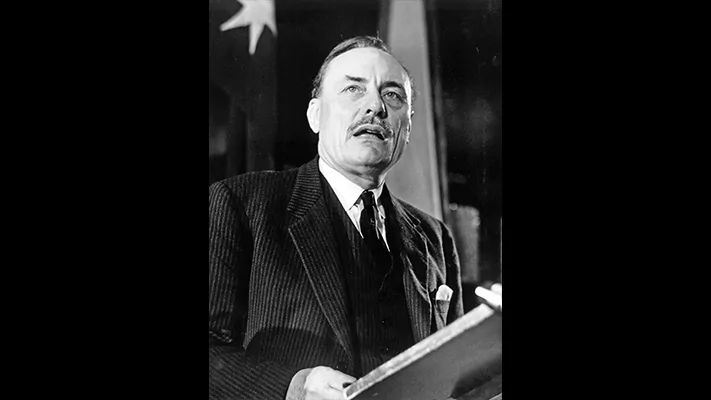

In 1968, the Conservative MP Enoch Powell warned that mass immigration from the former colonies of the British Empire, then running at about 50,000 people a year, was already causing a “total transformation to which there is no parallel in a thousand years of British history.” He predicted “tragic and intractable” racial conflict of “American proportions” by the end of the 20th century. He didn’t want Britain to join the European Union, either.

Powell was a classicist, so he quoted Virgil’s Aeneid: “As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding. Like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the river Tiber foaming with much blood’.” He was also a patrician dabbling as an opportunist, like one of the populares, the original populists, in the days when the Roman republic was unraveling. He intended, he told a friend, to make a speech that would “go up ‘fizz’ like a rocket. But whereas all rockets fall to the earth, this one is going to stay up.”

It did and it didn’t. The outcry from what we would now call “elite” opinion caused Powell’s party leader, the liberal conservative Edward Heath, to drop him from the shadow cabinet. Yet the popularity of Powell’s message among the public probably helped Heath win the 1970 elections. Powell left the Conservatives in 1974, when Heath committed his government to leading Britain into the European Economic Area, the forerunner of the European Union. Heath won a 1975 referendum on European membership by deliberately misleading the voters.

Powell lost the battle, but he is posthumously winning the war. He became a pariah in his party and the media, but his Rivers of Blood speech remains the most famous British speech since Winston Churchill’s wartime oratory. The muttered grumble “Enoch was right” became the most commonly voiced private opinion in Britain in the 1970s and 1980s. The two key figures in subsequent British conservatism were both Powellites. But only one of them, Margaret Thatcher, remained a Conservative.

The other, Nigel Farage, left the Conservative Party in disgust in 1992 when John Major’s government signed the Treaty on European Union. The “Maastricht Treaty” laid the legal path to the European superstate that Heath had promised would not and could not happen. A year later, Farage became a founding member of the U.K. Independence Party. Farage asked Powell to endorse UKIP and twice asked him to run as a UKIP candidate. Powell refused.

Sherry with Enoch

I had sherry with Enoch Powell in 1987. He gave a lunchtime talk at my school, and afterward, the headmaster invited that year’s applicants for the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge to join him and Powell for drinks. We stood in a half-circle while Powell ran a beady, slightly mad eye over us, inhaled sharply through his nose, then said, “Young men like you hold the future of this country in your hands.”

We thought he was an insane relic, a Monty Python caricature in a gray three-piece and an archaically clipped officer-class accent. But Powell was right. The future of the country really was in the hands of the privately educated young men of our generation — men such as Blair, Cameron, Johnson, Sunak, and Farage. And what they all wanted was mass immigration, except, that is, for Farage.

In the 2014 elections to the European Parliament, the U.K. Independence Party, led by Farage, became the first party in modern British history to beat both Labour and the Conservatives. Cameron, a liberal conservative prime minister not unlike Heath, responded by calling an election to restore the Conservatives as the voice of the Right. To undermine UKIP, Cameron promised that if he won, he would call a referendum to settle the issue of Britain and Europe once and for all. The Powellite revolt of the English that had begun in 2014 accelerated in the Brexit referendum in 2016 and again in Johnson’s landslide win in the 2019 elections. It shows no sign of stopping.

On June 13, Farage did it again. A YouGov poll for the Times newspaper put Farage’s Reform U.K. at 19%, a point ahead of the Conservatives. On June 19, a YouGov poll predicted an epochal landslide: Labour with a massive 425-seat majority, the Conservatives on only 108 seats, the worst result in their history. On the same day, a Savanta poll for the Daily Telegraph predicted 516 seats for Labour and only 53 for the Conservatives, with Sunak among those losing his seat.

With Labour so far ahead, Farage has declared that the election winner was obvious. What mattered now was who would lead the opposition. The combination of Britain’s first-past-the-post system and the equal spread of Reform U.K. support across the nation meant that YouGov predicted Reform U.K. will win only five seats. That, however, would put Farage where he has always wanted to be, on the benches of the House of Commons and as the Right’s most popular figure. He now promises a Powellite “reverse takeover” of the rump Conservatives and to run for the leadership in 2029.

Powell was wrong about racial conflict. By the end of the 1990s, Britain was the best integrated and least racist society in Europe. Though Powell spoke Urdu from his time in British India, he failed to foresee the rise of Islamism. Religion, not race, has become the most divisive issue in British politics. Still, he was right enough about what would happen when the majority started to feel like “strangers in their own country.”

Powell’s rocket is now so high that Sunak and Labour’s Keir Starmer are both promising to reduce immigration. There is no reason to believe them, just as there is no reason to believe Biden. Like Democrats calling a vote for Trump a vote for fascism, the British Conservatives are reduced to shaming voters into supporting them: If you vote for Reform U.K., you’re a “Labour enabler.”

Meanwhile, Reform U.K. launched its campaign with the Powellite claim that the Conservatives have overseen the biggest demographic alteration in England since the Norman Conquest of 1066.

Jupiter unfrocked

June’s elections to the European Parliament continued a two-decade trend. “New Right” parties such as France’s National Rally and Alternative for Germany continued to grow their vote at the expense of the Left and the Greens. The centrist vote stagnated. In France, the coalition Besoin d’Europe (“We Need Europe”), led by Macron’s Renaissance party, won only 14.6% of the vote. National Rally, the Eurosceptic and anti-immigration party led by Marine Le Pen, came first, with 31.37%.

Macron responded by calling for snap elections to the National Assembly, the French lower house. Macron has governed in the style of Cameron and Romney. He is socially liberal and economically conservative at a time when the voters, seeking protection from the effects of mass immigration and global markets, are becoming social conservatives and economic liberals. Consequently, his faction in the Assembly, La République En Marche (“The Republic on the March”) lost its majority in the national elections of 2022.

The constitutional peculiarities of the Fifth Republic make the French president unusually powerful if he has the Assembly’s support and still hard to dislodge if, as now, he presides over a divided Parliament. But an antagonistic majority can, if it wants, overthrow the government. In that scenario, the president, who is supposed to represent both the Assembly and the government, will come under immense pressure to resign.

Macron hopes that the snap election will force the voters and the centrist parties into le front républicain (“the republican front”) against the nationalists of the Right and the communists, environmentalists, and Islamists of the Left. This worked in 2002, when center-left voters backed a center-right Gaullist, Jacques Chirac, in order to exclude Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine’s flagrantly neofascist and racist father. It seems unlikely to work now.

Marine Le Pen has moderated her policies and rebranded her father’s thuggish National Front as the National Rally. While the taboo against the Le Pens was losing its power, Macron was exploiting popular anger at the ossification of French politics to collapse its beneficiaries, the centrist parties. Macron’s En Marche party shares its creator’s initials. It is little more than a personality cult for Macron as “Jupiter,” the French equivalent of MAGA, wielding bureaucratic efficiency and a bank manager’s suit instead of the pitchfork and the baseball cap. Macron has succeeded in trashing the center parties but not in building a new center.

Macron says the elections will rally a “silent majority” against the “political extremes,” but he has been crucial in driving the majority to the extremes. Les Républicains, the inheritors of the Gaullist, center-right mantle, have 62 members in the Assembly. National Rally, on 88 seats, is the real Right opposition. It’s even more extreme on the Left. The traditional center-left Socialists have only 31 seats. The real Left opposition is the eco-communist La France Insoumise (“France Undefeated”), with 75 seats.

When Macron called elections, the Socialists tried to form a left-wing coalition, but the other parties ignored them and formed a radical New Popular Front. The Republicans’ leader, Éric Ciotti, took the opposite tack. Once, the Republicans campaigned as the sensible, center-right bulwark against Le Pen. Now, Ciotti admitted that the Republicans’ policies have converged with National Rally’s and proposed an electoral alliance. The Republicans cannot beat National Rally, so they might as well join them or be pulverized.

Ciotti neglected to consult his party managers. The Republicans’ political bureau met without him, then announced it had fired him. Ciotti locked himself inside his party headquarters. His colleagues threatened to call the emergency services to break down the door, but the party secretary remembered she had a spare key. Effortlessly sustaining the farce in an effortlessly French silk scarf, she fumbled the ceremonial unlocking before the cameras.

Ciotti emerged to claim that the party bureau had not followed party rules, so he “is and remains president.” He still seems to control the party’s account on X. He claims that about 80 of the 93 current Republican deputies are willing to follow him into the arms of Marine Le Pen (formerly taboo) and her handsome young protege, Jordan Bardella (big on social media).

It’s possible that this would be enough to create a working majority for a National Rally government in the 577-seat Assembly. If so, Macron would have no choice but to accept a cohabitation with a National Rally administration and nominate Bardella as the new prime minister. The French president has a free hand on foreign and defense policy and on dealings with the European Union, but the Parliament controls France’s domestic policy. Imagine a President Kamala Harris having to accept Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) as the speaker of the House, but with stalemate not as an option.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Over the next year or so, the elections in the leading Western democracies will confirm that 2016 was not a one-off. It was the first of the shock waves that signal an earthquake. It is demolishing the centrist, managerial consensus that has ruled the West since the 1990s and taking down the parties as we have known them. The force-multiplying effects of social media mean that it may yet demolish politics as we have known it, too. Macron’s post-party rule by ego may be smoother than Trump’s, but neither could have risen to power without the convergence and collapse of the center.

Centrist politicians and their attendant media will panic about “populism” as usual and declare, as Biden likes to whisper in his clearer moments, that every election is the last battle of democracy and autocracy. It’s not. It’s how liberal democracy is renewing itself in a changed era and how nations are choosing to defend their social and cultural coherence in an era of unprecedented human mobility. If the traditional parties fail to adapt to their constituencies, they will go the way of the American Whigs in the 1840s, the British Liberals in the 1940s, and the Rockefeller Republicans in the 1960s.

Dominic Green is a Washington Examiner columnist and a fellow of the Royal Historical Society. Find him on Twitter @drdominicgreen.