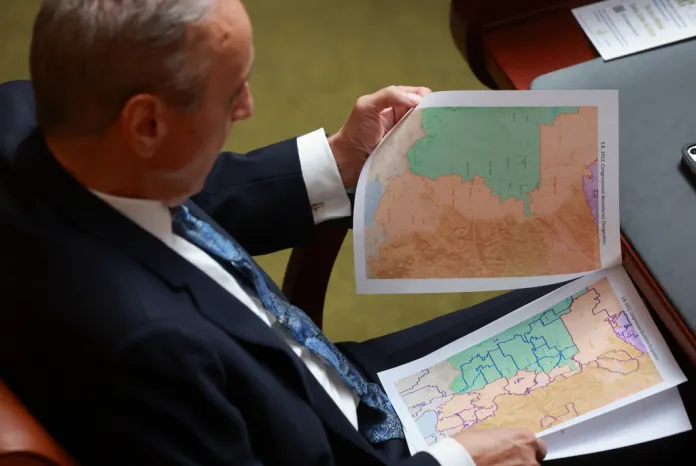

A federal court’s surprise decision to block Texas Republicans from using their newly-drawn congressional map for the 2026 midterm elections has turned what began as an aggressive mid-decade redistricting offensive into a far murkier fight over who controls the House next year.

The ruling, handed down Tuesday by a three-judge panel in El Paso, orders Texas to revert to the congressional lines it used in 2022 and 2024, at least for now. The court concluded that the 2025 map, pushed through the legislature at President Donald Trump’s urging, was an unlawful racial gerrymander rather than a run-of-the-mill partisan redraw.

Combined with a Utah judge’s move last week to scrap that state’s GOP-favored map in favor of a plaintiff-drawn plan that creates a Democratic-leaning Salt Lake City district, Republicans who hoped to build a mid-decade firewall are suddenly playing defense in courtrooms across the country.

At the same time, Democrats’ biggest redistricting victory of the cycle, California’s Proposition 50 map, which could net them as many as five seats, faces its own legal challenge after the Justice Department and Republican plaintiffs both sued to block it as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

Hovering over everything is the Supreme Court’s rehearing of Louisiana v. Callais, a case that could sharply narrow or even upend Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The timing of that ruling, potentially around or even before mid-January, will determine how much room states have to redraw lines — and how much chaos they’re willing to invite into a tight midterm calendar.

“Pretty much the only way to go about this is to assume that maps that have been passed are going to be the maps until stated otherwise,” Jacob Rubashkin, deputy director of Inside Elections, told the Washington Examiner. “But we should never discount the possibility of otherwise, even when it goes against the partisan framework that we all kind of approach the Supreme Court with these days.”

Texas ruling jolts Trump’s mid-decade strategy

In Texas, the three-judge panel’s 2–1 ruling is the clearest judicial rebuke yet to Trump’s call for red states to redraw maps mid-decade to pad the GOP’s slim 219–214 House majority.

U.S. District Judge Jeffrey Brown, joined by Senior Judge David Guaderrama, concluded that Gov. Greg Abbott (R) and the legislature effectively took their cues from a DOJ letter that flagged four “coalition districts” as potential racial gerrymanders, and then went far beyond that, dismantling multiple minority-heavy districts around the state.

Brown noted that Abbott specifically called lawmakers back into special session to “eliminate coalition districts and create new majority-Hispanic districts,” a record the panel said showed race, not party advantage, predominated decision-making. The court ordered Texas to keep using its 2021 map in 2026 while the case is appealed.

“The big question now is what the Supreme Court thinks the ‘status quo’ is,” Rubashkin said, noting that Texas’s appeal goes directly to the justices. “Is it the old map that produced the current delegation, or the most recent map the legislature passed? Either way, it is more likely today that Texas uses its old map than it was yesterday.”

With a Dec. 8 filing deadline looming for congressional candidates in Texas, the panel brushed aside arguments that its ruling would destabilize the 2026 elections, implicitly blaming lawmakers for waiting until this summer to redraw lines.

Utah and Indiana show smaller setbacks to GOP’s mid-decade gambit

If Texas is a legal setback for Republicans, Utah is a pure map loss.

On Nov. 11, 3rd District Judge Dianna Gibson ruled that the legislature’s “Map C” violated the state’s voter-approved Proposition 4, which set out neutral criteria and an independent redistricting commission process. Working up against a Nov. 10 “drop-dead” deadline set by the lieutenant governor, Gibson instead selected the plaintiffs’ “Map 1,” which keeps most of Democrat-leaning Salt Lake County in a single district and gives Democrats a realistic shot at one of Utah’s four House seats.

Utah House Speaker Mike Schultz has accused the court of deliberately waiting until the last minute to rule, effectively preventing an emergency appeal before counties must start preparations for candidate filings in January. GOP lawmakers are now weighing an appeal and even talk of impeachment, while Gibson and court staff have received threats since the ruling.

Henry Olsen, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, told the Washington Examiner the plaintiffs’ plan simply reflects the state’s natural political geography.

“If you were just doing a good-government map, you’d keep Salt Lake County largely whole, and that produces a safe Democratic seat,” Olsen said. “Republicans tried to avoid that by slicing Salt Lake into four rural-anchored districts. The judge is essentially saying state law doesn’t let them do that.” He noted that Republicans sought to minimize the chance of such a seat by splitting Salt Lake County and attaching its pieces to rural territory.

Meanwhile, Indiana Senate Republicans announced Friday they will not return in December for a special session to redraw congressional lines, despite strong pressure from Republican heavyweights including Trump and Gov. Mike Braun. The decision effectively kills, at least for now, an effort Republicans hoped could yield more favorable districts.

Olsen said he believes the impact from Indiana’s choice likely won’t move the needle, saying that “Realistically, Indiana Republicans could only move one seat.”

“Theoretically, they could move two, but that would require doing something they surely would not want to do, which is cut up the African American neighborhoods of Indianapolis and send them into rural districts. So would Republicans rather have an extra seat in the Gary area Yes. Is that determinative? Probably not,” Olsen said.

Still, in a 435-seat House where just three or four districts can decide control, Rubashkin warned against dismissing such incremental fights. “Republicans were never going to be able to redistrict their way out of a wave election,” he said. “But there was a universe in which they could have redistricted their way out of a ripple election, and they haven’t gotten the ripples they were counting on.”

Kansas Republicans, meanwhile, failed to muster the votes for a special session to redraw Rep. Sharice Davids’s (D-KS) district this fall, another sign that some GOP state legislators are wary of mid-cycle gerrymanders.

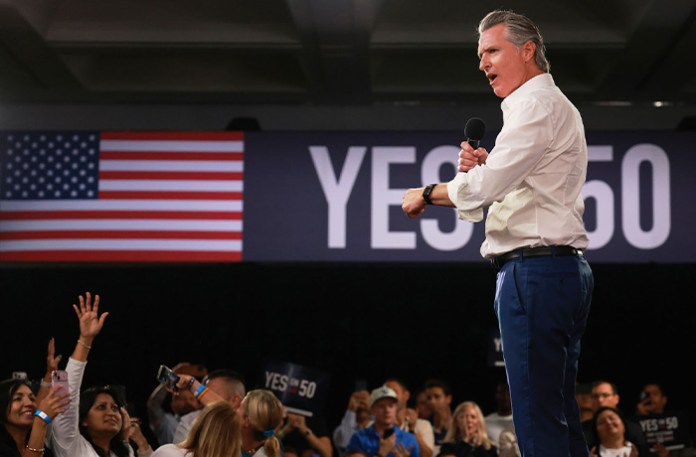

California flips the map — and lands in court

While Republicans stumble in red states, California Democrats have already banked what could be the single biggest map gain of the cycle.

Voters there approved Proposition 50 this month, scrapping the state’s independent commission process and empowering the legislature and Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) to enact a new congressional map projected to give Democrats as many as five additional seats.

But within days, the plan drew fire from GOP plaintiffs and the federal government.

The DOJ joined in a lawsuit against Newsom and state officials last week, alleging that Prop 50’s map is an impermissible racial gerrymander that lets Latino demographics “predominate” in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. The overarching case, backed by Golden State Republicans, argues the map intentionally favors one racial group at others’ expense and seeks to block the lines before candidate signature-gathering begins on Dec. 19.

Olsen said that even if the courts ultimately agree the legislature leaned too heavily on race, Republicans should temper their expectations.

“It appears they were drawing a partisan gerrymander,” he said, adding that in many of the areas at issue, “it’s very difficult to draw Republican seats” no matter how the lines are configured. In the Central Valley, undoing some Hispanic-opportunity districts “would probably give Republicans one or two extra seats,” he said, but elsewhere, including much of Los Angeles, it is hard to see large GOP gains.

“You’re not talking about a massive change — two or three seats,” Olsen said. “Republicans should fight for that, from their perspective, but that’s what we’re talking about.”

For now, he said, “I think it is reasonable to presume that these maps will go into effect,” estimating there is a “90 percent shot” California’s new lines will be used in 2026.

Callais and the power of deadlines

Even as individual states trade wins and losses, the biggest unknown is what the Supreme Court does with Louisiana v. Callais.

In June, the justices took the unusual step of ordering the case restored to the calendar for re-argument and explicitly asked the parties to brief whether Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which civil rights proponents defend as the core federal protection against racial vote dilution, remains constitutional.

A majority of justices on the high court signaled in October that they are open to limiting sharply how race can be used in map-drawing, a move that could invite Republican legislatures across the South to dismantle minority opportunity districts — or, conversely, leave them intact but strip away the legal theory Democrats have relied on to challenge GOP maps.

Rubashkin, however, cautioned against assuming the court is certain to gut Section 2, pointing back to its 2023 decision in Merrill v. Milligan, where the justices stunned many observers by reaffirming VRA protections. That ultimately led to the creation of a second black-majority district in Alabama.

“There was a lot of confidence that this court would not go along with the trial court’s determination,” Rubashkin said. “And of course, the court, in fact, said it was not only not going to strike down the remaining parts of the VRA, but was going to essentially add in something akin to proportionality in Alabama and Louisiana. That was a signal that these cases can move in unexpected directions.”

Meanwhile, some states are quietly rewriting their election calendars to give themselves more room to react. Louisiana has already pushed its filing deadline and congressional primary deeper into 2026 to account for a possible early Callais decision. Alabama’s GOP-run legislature is considering a bill that would trigger special primaries in districts affected by late map changes, allowing the state to adjust after a Supreme Court ruling without blowing up the general-election schedule.

Rubashkin noted that in past cycles, New York lawmakers changed both filing deadlines and primary dates to accommodate late redistricting.

“Courts seem to try and want to minimize disruption,” he said, “but it’s not a requirement that they issue their decisions in a way that causes minimal disruption. If the courts want to cause more disruption, they’re within their powers to do so, and the legislature is within its power to alter the primary schedule as well.”

Net advantage: Democrats, for now

Taken together, the mid-decade map wars have not produced the clean Republican advantage Trump and his allies may have envisioned when Texas kicked off the cycle by reopening its congressional lines.

Democrats have already banked a second black-majority seat in Alabama for the rest of the decade, a new Democratic-leaning district in Utah for 2026, and a California map that, unless courts intervene, could add several more Democratic seats.

On the Republican side, Texas’s attempt to create five new GOP-friendly seats is tied up in court, Indiana Republicans have balked at a special session, Kansas has shelved its own mid-cycle push for now.

“As of mid-November, this has been a rough two-week stretch for the Republican redistricting effort,” Rubashkin said, citing the Ohio compromise map, the Utah ruling, the margin of Prop 50’s passage and the new threat to Texas’s map. “Absolutely, there has been a clear loss of momentum for a project that started with such intensity down in Texas.”

COURT BLOCKS NEW TEXAS CONGRESSIONAL MAP FOR 2026 ELECTION

Florida, meanwhile, is shaping up to be the GOP’s last major offensive weapon. Florida House Speaker Daniel Perez quietly scheduled the first meeting of the legislature’s Select Committee on Congressional Redistricting for Dec. 4, setting in motion what could become the most consequential mid-decade redraw in the country.

The special committee was created in August in response to post-2020 population shifts, but its political significance is far larger, as Republicans already hold 20 of the state’s 28 House seats, and party leaders believe a new map could add as many as five more. Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) has signaled his support for the effort and has said he expects the formal redistricting process to begin in spring 2026.