“An autobiography is not our private story, but rather the baggage we carry with us,” Pope Francis said in his recollections, which were published this year. As the head of the Catholic Church for a dozen years, Francis was known for carrying his own bags, settling his own bills, and making his own phone calls.

Francis’s style was often freewheeling and flirted with chaos. He once told a World Youth Day audience to go out there and “make a mess.” For the early part of his pontificate, at least, the Vatican press officers frequently had to clarify his remarks.

Born Jorge Bergoglio in 1936 in Argentina’s capital, Buenos Aires, he became a priest of the Jesuit order and a bishop under Pope John Paul II. He then became a most improbable pope when Pope Benedict XVI unexpectedly resigned from office in 2013.

Bergoglio took the name Francis not after St. Francis Xavier, co-founder of the Jesuit order, but St. Francis of Assisi, who created the movement that became the Franciscan order. There is a story there that gets at his gift for improvisation.

Cardinal Claudio Hummes embraced Francis just after he was elected pope and before he was announced to the world. Hummes reminded the new pontiff not to forget the poor.

“It was then that the name Francis appeared,” he said in his autobiography Hope, and so Francis it was.

The introduction of a new pope can be a regal affair, with crowns and fancy garments. Not so for Francis. He met the crowd that packed into St. Peter’s Square wearing his simple white cassock.

Francis led the crowd in familiar Catholic prayers, the Our Father, the Hail Mary, and the Glory Be, for the benefit of his still-living predecessor, Benedict (who would live on until 2022). Before he blessed them, the new bishop of Rome asked the hundreds of thousands of faithful assembled there to first pray for him.

It made for a good first impression and cemented Francis’s reputation for humility. That wasn’t the whole truth about the man or his papacy, but it’s the one that stuck.

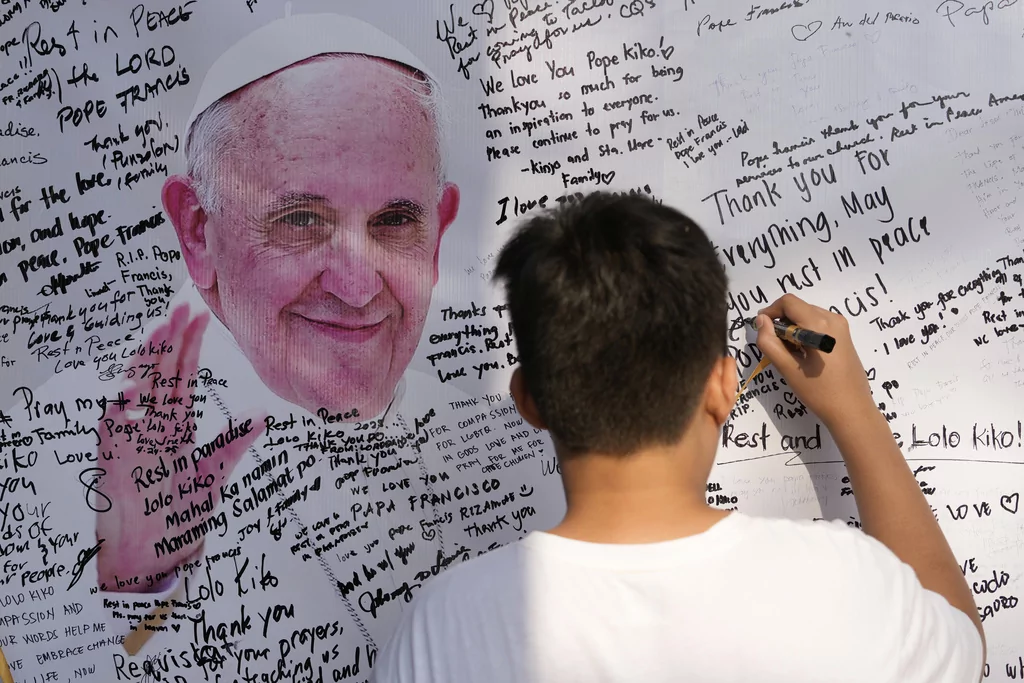

“A humble leader in tumultuous times,” a representative headline in the Seattle Times said after Francis, 88, died this Easter Monday from complications following a stroke.

Hope during lockdown

The times were indeed tumultuous. Francis became the pope of the pandemic. Much of the world went into government-imposed lockdowns for more than a year to try to stop the spread of the deadly virus COVID-19. Italy, which surrounds the tiny Vatican city-state, was more stringent than most nations. At the same time, Catholic churches around the world faced closures and other restrictions.

Francis responded to the pandemic in a number of ways, most strikingly by giving what is called the Urbi et Orbi (“city and world”) blessing from St. Peter’s Basilica in late March 2020. Normally, this blessing takes place with packed crowds. Instead, the pope was practically alone. Video captured him lifting the monstrance, the golden vessel containing a consecrated host, aka a communion wafer, skyward, and praying that this pestilence would pass.

“We find ourselves afraid and lost,” he preached in a homily the day before the solitary blessing. “Like the disciples in the Gospel, we were caught off guard by an unexpected, turbulent storm. … Just like those disciples, who spoke anxiously with one voice, saying ‘We are perishing,’ so we too have realized that we cannot go on thinking of ourselves, but only together can we do this.”

Francis thought COVID-19 exposed a spiritual crisis in modern man as well.

“The tempest lays bare all our prepackaged ideas and forgetfulness of what nourishes our people’s souls,” he preached. What really mattered was “putting us in touch with our roots and keeping alive the memory of those who have gone before us,” he said, which would give us the “antibodies we need to confront adversity.”

Vice President JD Vance, a Catholic convert, met with Francis the day before his death as part of a trip to India to further trade. He admired that message.

“I was happy to see him yesterday, though he was obviously very ill. But I’ll always remember him for the … homily he gave in the very early days of COVID,” Vance said. “It was really quite beautiful.”

President Donald Trump is not Catholic and is willing to tangle with clerics who call him out. Francis did this, at times vehemently, over immigration and other matters. But this was not a fight the president was willing to have. He ordered all U.S. government flags lowered to half-mast over the death of the pope.

“He was a good man, worked hard, he loved the world, and it was an honor to do that,” Trump said, flanked by his wife, first lady Melania Trump, on one side and someone in an Easter Bunny costume on the other.

No longer Italian?

For over 450 years, beginning in the 1520s, popes didn’t just live in what would become the nation of Italy. They were also from there. Two factors contributing to this Italian domination were the location of the Vatican with the bishop-heavy curial bureaucracy that runs the larger church and the previous robustness of Italian Catholicism. Italians used to comprise a huge voting bloc every time a new pope was elected.

However, the last three popes have not been Italian. Paul II hailed from Poland, Benedict XVI from Germany, and Francis from South America. What caused the College of Cardinals — the roughly 120 bishops charged with electing the pope — to go in a different direction?

Many historians point to the brief 33-day papacy of John Paul I, an Italian named Albino Luciani, as the decisive break. His unexpected death made 1978 the infamous “year of three popes.” Benedict XVI later explained that many cardinals believed that they were being nudged by the Holy Spirit to go in a different direction.

These three non-Italian popes put their own stamps on the larger Catholic Church. Paul II helped stiffen the church and the world’s spine in the face of Soviet aggression on his native soil. Benedict XVI’s twin pursuits were renewing the church’s tradition and mending ancient fissures. Significant ecumenical progress was made on his watch, which helped to smooth previous Catholic-Orthodox tensions.

It’s impossible to know exactly what the College of Cardinals will do when they convene in a week or so, but the math makes it less likely they will put the genie back in the olive oil bottle, so to speak.

True, the Canadian betting market Bet365 gives Pietro Parolin, an Italian cardinal and former Vatican secretary of state, the best chance of being named the next pope, and the amusingly named Archbishop Pierbattista Pizzaballa is also in the running. There are also many other plausible candidates outside of Italy who are generating chatter, including Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle of the Philippines and Cardinal Peter Turkson of Ghana.

Whether or not an African lands on the chair of St. Peter when the voting stops this time, an African is likely to be a very strong contender in the near future. Or so suggested Philip Jenkins, historian of religion at Baylor University.

“The church’s global population is now 1.4 billion, of whom 27.4% live in South America, 20.4% in Europe, and 20% in Africa,” Jenkins said in a blog post titled “The Triumph of Catholic Africa,” which he pointed the Washington Examiner to. Moreover, he said, “By about 2026, there will be as many Catholics in Africa as in Europe.”

Jenkins explained what happened: “Since the start of the twentieth century, Christian missions generally achieved widespread successes in Africa, and the churches they planted built massively on those original successes.”

Population growth matters as well. Africa’s numbers are currently surging while most of the rest of the world is stagnating.

The future of the church

An African pope and a growing African Catholicism could create some tricky problems for Catholic churches worldwide. Africans tend to be quite conservative doctrinally, if not politically. This has put strain on Western churches with a significant African cohort.

For instance, the United Methodist Church is experiencing a massive breakup, with thousands of churches leaving. The tug-of-war is over many social issues, with American and African traditionalists on one side and theological liberals on the other.

This could create problems for the stamp that Francis tried to put on the church. Though it’s not entirely fair to call him a theological liberal, it’s not entirely unfair either. For instance, he tried and failed to find a way to bring more divorced Catholics into communion.

Perhaps stemming from that failure, Francis struck out at Catholics who prefer the Latin Mass. Benedict XVI worked to give them a solid footing within the church. Francis made it much harder for them, limiting when and how often Latin Masses can be said at most parishes. A more theologically conservative pope, African or otherwise, might reverse that yet again.

Other issues were more of a muddle. Francis said Catholics certainly didn’t have to breed “like rabbits,” but his final Easter message insisted that “God created us for life and wants the human family to rise again! In his eyes, every life is precious! The life of a child in the mother’s womb, as well as the lives of the elderly and the sick, who in more and more countries are looked upon as people to be discarded.”

The issue of priestly sexual abuse was not one that he was up to tackling. Though he always condemned abuse, Francis’s unsystematic and personalist approach did not allow for larger reforms that might help in the future.

He also desperately wanted peace, calling for ceasefires in both Ukraine and Gaza in his final Easter message.

“The growing climate of anti-Semitism throughout the world is worrisome,” Francis said. “Yet at the same time, I think of the people of Gaza, and its Christian community in particular, where the terrible conflict continues to cause death and destruction and to create a dramatic and deplorable humanitarian situation. I appeal to the warring parties: call a ceasefire, release the hostages, and come to the aid of a starving people that aspires to a future of peace!”

POPE FRANCIS DEFIED EASY POLITICAL CATEGORIZATION

After his death, we learned Francis did not simply wish Catholics from Gaza well in the abstract. He took a direct personal interest in the well-being of about 300 Catholics sheltered in a church there. In fact, he called them every day at 7 p.m.

“He would ask us how we were, what did we eat, did we have clean water, was anyone injured?” George Anton, spokesman for the Church of the Holy Family, told NPR in an interview. “It was never diplomatic or a matter of obligation. It was the questions a father would ask.”

Jeremy Lott is the author of The Warm Bucket Brigade: The Story of the American Vice Presidency.