Several moms in suburban St. Louis have been working to get toxic sites in the area cleaned up, a major undertaking to fix widespread contamination that some government officials apparently covered up for decades.

“This was the best kept secret of St. Louis. The Manhattan Project wasn’t well known here, and it’s still a pretty good secret here,” Just Moms STL co-founder Karen Nickel said.

Nickel formed her group alongside her neighbor, Dawn Chapman, in 2013.

“Over the years, we had heard bits and pieces of the story and what we thought was the story,” Nickel said.

MORE PEOPLE EXPOSED TO MANHATTAN PROJECT CHEMICALS DESERVE COMPENSATION, ADVOCATES SAY

The two moms spent several years going through thousands of documents that revealed those in charge of disposing of toxic waste in Missouri likely knew that crew had mishandled those chemicals.

“Right away, we were going, ‘Oh my God. This is so different than what we thought,”’ Chapman said.

Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., said, over time, more details about the Manhattan Project in St. Louis came to light.

“As early as the 1960s, you had the public beginning to get some sense of it. But really, it wasn’t until the ‘80s and the ’90s that the full scope of this began to come into view,” Hawley said.

“As recently as last year, we got a new cache of documents that showed the full extent of the government’s knowledge and what the government knew years ago — 30, 40, 50 years ago — that they had poisoned the creek, that their landfill that they dumped the waste into was going to cause huge problems, environmental problems and health problems. And they lied about it.”

ENVIRONMENTALISTS CALL ON BIDEN ADMIN TO TANK NATURAL GAS PROJECT AMID NATIONWIDE ARCTIC BLAST

Hawley is pushing to expand and extend the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, which will expire this year. The legislation would make it so people who may have been sickened by chemicals in St. Louis and other areas could receive compensation from the government.

“We’ve come to find that St. Louis was a uranium processing site. So was Kentucky. So was Tennessee, that the extent of the testing that was done in the West was far greater than we knew,” Hawley said.

The documents included internal memos from Mallinckrodt Chemical Works, a company hired by the U.S. government to process chemicals for nuclear weapons. The cache also included testing and sampling from government agencies as well as warnings that sites exposed to those chemicals may not have been safe.

SEE THE DOCUMENTS BELOW. APP USERS: CLICK HERE.

“The evidence was there, the facts were there, and it told the story from beginning to end,” Nickel said.

Mallinckrodt Chemical Works in St. Louis worked to process uranium that would eventually help create the first sustained nuclear chain reaction. After the plant shut down, the company worked to dispose of the chemicals. An internal memo from 1949 revealed workers discussed health and safety concerns that came with where they stored the waste.

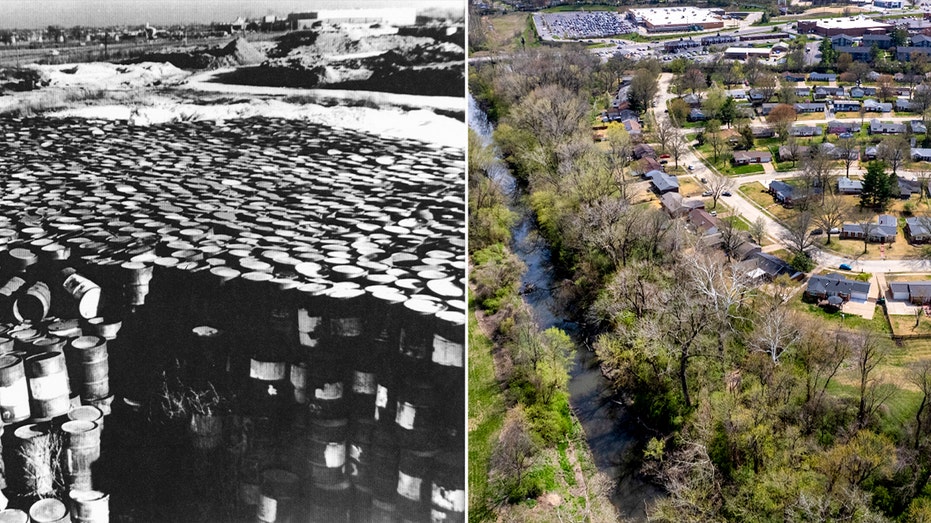

“Point No. 2 concerns the problem of the disintegrating K-65 drums at the airport,” the memo stated. “This is recognized as a severe problem.”

Federal officials first stored the waste at a site near St. Louis Airport. The location was near a creek that stretched 14 miles through North St. Louis County. The barrels were left out in the open and exposed to the elements.

“Right away, you could see that the government knew how dangerous this waste was,” Chapman said.

WHITE HOUSE ECO COUNCIL AT ODDS OVER TECHNOLOGY CENTRAL TO BIDEN’S GREEN GOALS

The internal memo from Mallinckrodt detailed concerns among workers that the chemicals could have leaked into the creek.”

The health hazard to workers handling the K-65 material, especially in broken drums, is much more serious and immediate than the possible hazard of stream pollution,” it said.

“They were so toxic that they were told, ‘Do not touch those. Those are too dangerous,’” Nickel said.

High water and flooding have been additional yearly concerns along Coldwater Creek.

“Of course, they wouldn’t put dangerous waste next to a creek that floods,” Chapman said. “They knew it was probably leaking into the creek, but they didn’t know how much.”

Army Corps of Engineers officials said because of the flooding throughout decades, their cleanup job today has been complex.

JOE MANCHIN THREATENS TO OPPOSE BIDEN NOMINEES OVER UPCOMING POWER PLANT CRACKDOWN

“Wind and rain, and also flooding events, took some of those contaminants, and they were carried down the stream in the sediment and then deposited during flooding events and also just during the normal flow,” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers St. Louis District Program Manager Phil Moser said. “This is all historical contamination from decades ago, and that’s why it’s so difficult today finding this contamination.”

The Army Corps of Engineers has been sampling for radioactive material all along Coldwater Creek, some of which dated to before the St. Louis population boom.

“This was before homes were built. And lo and behold, in the late ‘50s and ’60s, homes were being built on top of this,” Nickel said.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, crews moved the waste to a different location near the airport and again left it out in the open.

“The controls back in the day were surely not what they are now. That’s why we’re in the current situation,” Moser said.

Advocates and lawmakers, including Hawley, said the cleanup could move faster.

“For years, the people of St. Louis were told, ‘Don’t worry. There’s no significant radiation.’ Or they were told, ‘Hey, we’ve cleaned it all up.’ In fact, those things were not true,” Hawley said.

“It was taking years to do testing and really get the scope and magnitude of how contaminated North County is,” Chapman said.

Testing from almost 50 years ago found possible contamination in parts of the creek. A 1977 report from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee detailed samples from Coldwater Creek. Testing in drainage ditches, which carried run-off water into the creek, showed average radiation levels were almost five times higher than usual.

“We haven’t seen that level at these sites, since I’ve been here for sure,” Moser said.

In the 1970s, workers moved the waste once again, this time to West Lake Landfill in Bridgeton, Missouri.

“It is not possible in this United States of America to purchase a home next to a site that has Manhattan Project radioactive waste just sitting up for decades,” Chapman said.

Chadman, Nickel and thousands of others eventually would call neighborhoods near the West Lake Landfill home.

“The time to act is now. This should have been done 50 years ago, but it hasn’t been. So, now it’s time to do it,” Hawley said.