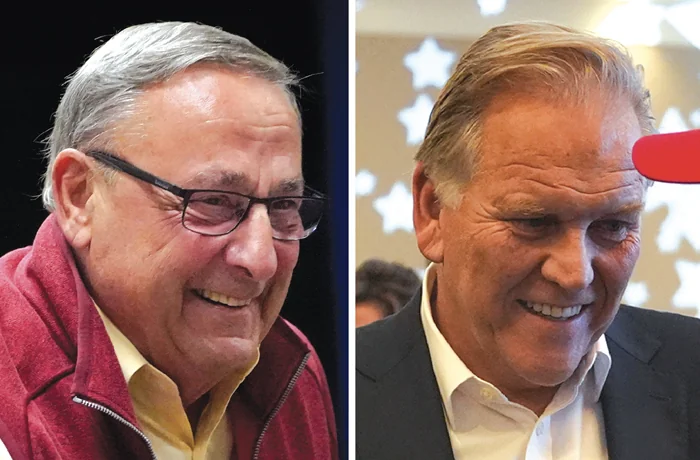

MIAMI — Former Maine Gov. Paul LePage and ex-Rep. Mike Rogers of Michigan hardly stood out among Florida residents. The Republican pair had joined many former constituents who bolted those cold-winter states for the Sunshine State’s balmier environs.

But political ambition beckoned. So, LePage and Rogers returned to their home states to run for office again. Both lost, LePage in the 2022 Maine governor’s race and Rogers in his 2024 Michigan Senate bid.

That hasn’t dissuaded them from second comeback bids. LePage, in November 2026, aims to knock off the Democratic incumbent in Maine’s sprawling northern House district. Rogers is again seeking an open Senate seat in Michigan.

As the 2026 election cycle intensifies, both are likely to, again, face questions about their Florida sojourns. The political cultures of places such as Maine and Michigan often differ from Florida itself, where it’s no big deal to run for office after growing up, and even spending a portion of adulthood, out of state. The official Florida legislature handbook’s biographical information section for each lawmaker includes a “Moved To Florida” line if it applies, along with data such as birthdates.

A swath of Florida’s congressional delegation is originally from out of state, living in other places until leaving for college, the military, or later in adulthood. Among them are Sen. Rick Scott (R-FL) and Reps. Kat Cammack (R-FL), Byron Donalds (R-FL), Neal Dunn (R-FL), Randy Fine (R-FL), Lois Frankel (D-FL), Anna Paulina Luna (R-FL), Brian Mast (R-FL), Darren Soto (D-FL), and Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL). That each successfully pursued a political career throughout Florida makes sense in one of the nation’s fastest-growing states.

“After decades of rapid population increase, Florida now is the nation’s fastest-growing state for the first time since 1957, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Vintage 2022 population estimates,” the federal agency reported in December of that year. “Florida’s population increased by 1.9% to 22,244,823 between 2021 and 2022, surpassing Idaho, the previous year’s fastest-growing state.”

Florida’s population grew by 2% between 2023 and 2024, with the state gaining 467,347 residents, per the Census Bureau. This growth rate was second only to the District of Columbia’s 2.2%. By contrast, Michigan over that time grew only 0.6%, to 10,140,459 people. And the Maine population increased a mere 0.4%, to 1,405,012 people.

In slow-growth states with frigid winters, moving from Florida and then back again can be a touchy matter because generations of voters stay put without the option of spending the cold months in a place such as Florida.

Former governor aims to turn over a new LePage

LePage announced on May 5 that he’d run for Maine’s 2nd Congressional District. It’s the largest House district east of the Mississippi River, covering 85% of the state, from north of Portland up to the U.S.-Canada border. Heavily forested, it’s larger than the New England states of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont combined.

LePage, 76, gives Republicans a well-known candidate to take on Rep. Jared Golden (D-ME) in a conservative-leaning district the GOP has repeatedly targeted. But LePage, governor from 2011 to 2019, brings plenty of political baggage.

LePage, as governor, presaged the type of smash-mouth politics popularized by President Donald Trump in his three White House campaigns — winning in 2016, losing in 2020, and then reclaiming the office four years later. In 2016, for instance, LePage described the state’s opioid epidemic on “guys with the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty” who “come from Connecticut and New York” to “sell their heroin” then “go back home.”

He added, “Incidentally, half the time, they impregnate a young white girl before they leave, which is a real sad thing because then we have another issue we’ve got to deal with down the road.”

And LePage’s recent electoral track record there has been less than stellar. He lost a 2022 bid for his old job to Gov. Janet Mills (D-ME), his gubernatorial successor in the 2018 election, by a 56%-42% margin.

Part of LePage’s problem in that campaign was eroded ties to his home state. Immediately after Mills succeeded LePage, on Jan. 2, 2019, he registered to vote in Florida. LePage’s listed residence was in Ormond Beach, a city of about 45,000 people directly north of Daytona Beach, on Florida’s upper Atlantic Coast. LePage said at the time that he planned to live in Florida for the majority of the year and become a legal resident there to pay no income tax and lower property taxes.

That’s a standard move for many Florida residents who come from elsewhere, and one thing any decent accountant would advise so a client could minimize annual tax liability. But it’s likely to provide political fodder for LePage’s 2026 opponent, Golden, because Democrats likely need to hold the seat to have any chance at winning a House majority in the midterm elections.

Mr. Rogers’s neighborhoods

In Michigan, Rogers is making his second straight Senate bid, aiming to fill the seat of retiring Sen. Gary Peters (D-MI). The Trump White House and Senate Republicans favor Rogers for the GOP nomination, though he could still face a primary fight.

Rogers, 62, represented a Lansing-based district in the House from 2001 to 2015. During his final four years in Congress, he was the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee.

After retiring from the House, Rogers hosted a radio show, engaged in some consulting, per campaign financial disclosure forms, and ultimately moved to Florida. He was registered to vote and owned a home in Cape Coral, a southwest Florida community. Known for its canals, the city of nearly 230,000 people, about 83 miles south of Sarasota on Florida’s Gulf Coast, is home to many retirees who were FBI agents and employees of various intelligence services. Rogers himself, after three years in the Army, was an FBI special agent from 1989 to 1994 in the agency’s Chicago office, specializing in organized crime and public corruption.

Rogers insists he always kept up his Michigan ties, and in 2023, he bought property again in the Wolverine State. He reentered politics in Michigan, losing a Senate bid against Sen. Elissa Slotkin (D-MI) in what was an open seat race.

Slotkin won 48.64%-48.30%, a difference of 19,006 votes out of nearly 5.6 million cast. In those kinds of agonizingly close losses, any number of factors could have made a difference or been decisive. And while it’s impossible to blame Rogers’s loss solely on the Florida residency issue, or any other specific line of criticism, he did spend much of the campaign on the defensive over why he left Michigan in the first place.

It was part of a broader line of criticism over political shape-shifting. The jut-jawed and barrel-chested military veteran and FBI agent, before turning to politics, was a legislative foot-soldier out of central casting in the post-9/11 “War on Terror” era. Rogers was first elected to the House in 2000 after nearly six years as a state senator, beginning his Capitol Hill tenure with new President George W. Bush.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, eight months into Rogers’s first House term, he loyally backed the Bush administration’s antiterrorism agenda, including the Iraq War resolution in 2002 and the Military Commissions Act of 2006, which authorized the use of such panels to try noncitizen “unlawful enemy combatants” for violations of the law of war. The Supreme Court, in 2008, ruled that a key section of the law was unconstitutional, declaring that detainees had the right to petition federal courts for challenges to the legal recourse of habeas corpus.

Yet when Rogers ran for the Senate in 2024, after a decade out of office, he became a deep skeptic of federal law enforcement. The one-time FBI agent echoed the whines of Trump, between his presidential terms, about a “witch hunt” through political prosecutions, and the investigation over Russia’s role in aiding the 2016 GOP nominee.

Rogers’s move to Florida and back to Michigan became part of a broader Democratic campaign against his alleged political chameleon tendencies. The ferocity and intensity of the Democratic campaign attacks on Rogers over the Florida residency matter suggest it cut deep.

“With four days left until Election Day, Mike Rogers has given Michiganders countless reasons not to trust him to represent Michigan in the Senate,” the Michigan Democratic Party said in a statement as Election Day neared. “After lying for months about where he lives, Mike Rogers finally admits that he is not living at the house that he claims to. The house that Rogers claimed to live in ‘had no certificate of occupancy,’ and it appears ‘to be still in a construction phase, with an unfinished deck and a Port-A-Jon next to the driveway.’”

A DAY WITH FLORIDA STATE TROOPERS NABBING ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS FOR ‘ALLIGATOR ALCATRAZ’

The attacks worked in 2024, even as Trump won the state’s electoral votes on his way back to the presidency. It’s likely to be a political line of criticism by the winner of the 2026 Democratic Senate primary, in which candidates include Rep. Haley Stevens (D-MI); state Sen. Mallory McMorrow; Dr. Abdul El Sayd, who was previously Wayne County health director; and state Rep. Joe Tate, speaker of the Michigan House of Representatives from 2023 to 2025.

None of them has previously lived in Florida.