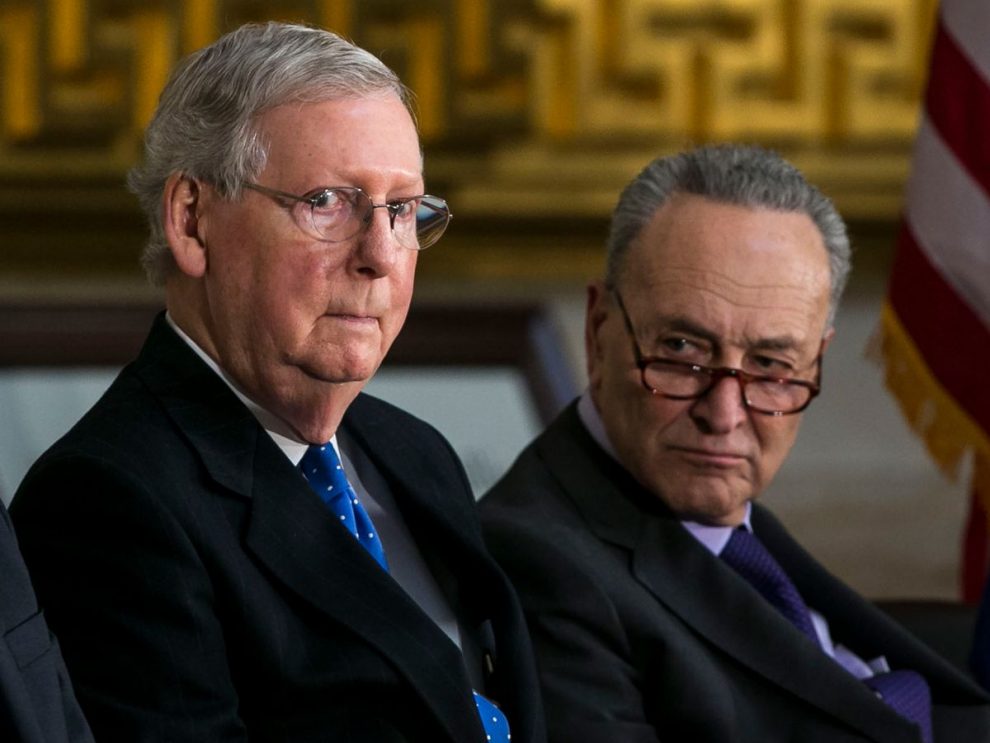

The relationship between Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Minority Leader Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) has hit a new low after the bitter fight over newly sworn in Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

The rancorous nature of their relationship was on full display Monday evening, moments before the Senate voted to confirm Barrett along party lines, when Schumer declared it would “go down as one of the darkest days in the 231-year history of the Senate.”

The deterioration of their relationship in recent months, a tense election year when control of the Senate in 2021 is at stake, raises questions about their ability to work together in the future and whether Democrats will change the chamber’s rules once in power to circumvent McConnell entirely.

A growing number of Democrats are pushing for Schumer to eliminate the legislative filibuster if they win the Senate majority.

Schumer on Monday slammed McConnell personally, accusing him of hypocrisy and lying. He also offered a chilling warning of what Republicans might expect if Democrats win back control of the Senate on Nov. 3.

“The next time the American people give Democrats a majority in this chamber, you will have forfeited the right to tell us how to run that majority,” he said. “I know you think that this will eventually blow over. But you are wrong.”

“My colleagues may regret this for a lot longer than they think,” he later added.

When it was McConnell’s turn to speak, instead of basking in the glow of a major Republican victory, he spent much of his speech laying into Schumer.

The GOP leader dismissed Schumer’s allegations of impropriety as “outlandish” and “utterly absurd.”

He also got down to a personal level, accusing Schumer of threatening conservative justices on the court. McConnell noted that earlier this year at a rally outside the high court, Schumer said President Trump’s appointed Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh would “pay the price” for rolling back abortion rights.

Schumer, walking out of the Senate after the vote Monday evening, told reporters: “I have two words for McConnell’s speech: very defensive.”

Much of the bitterness stems from McConnell’s decision to refuse President Obama’s final Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland, a hearing or a floor vote in 2016 because of what he said was the need of the American people to weigh in on the choice in that year’s presidential election. And when McConnell then announced last month that he was going to speed Barrett’s nomination through the Senate less than a month before Election Day, it outraged Democrats.

McConnell has tried to draw a distinction between 2016 and 2020 by pointing out that the White House and Senate were split between the parties four years ago and now both are unified under Republican control. The explanation did nothing to soothe furious Democrats.

However, the tension between the two leaders was clear to see even before Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s death and the battle over her seat.

McConnell declined to negotiate directly with Schumer and Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) after the coronavirus pandemic hit and Congress hurriedly put together the $2.2 trillion CARES Act. White House negotiators led by Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin had to shuttle back and forth between McConnell’s and Schumer’s offices to put together a deal in the late hours of the night.

Before the pandemic, Schumer and McConnell fought bitterly over the rules for Trump’s impeachment trial. The Democratic leader blasted it as “a sham,” “a perfidy” and “one of the worst tragedies that the Senate has ever overcome” after McConnell and most of his conference refused to allow additional witnesses.

The episode showed how much the relationship between the Senate’s top leaders had eroded since President Clinton’s impeachment trial in 1999, when then-Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott (R-Miss.) and Democratic Leader Tom Daschle (S.D.) were able to hammer out an impeachment resolution that passed the chamber unanimously.

This year, McConnell didn’t reach out to Schumer to attempt to negotiate a bipartisan resolution. He also left his counterpart in the dark for weeks in April about his plans to negotiate another coronavirus relief package.

“Look, I try to get along with everybody and — but he’s not very talkative, let’s put it like that,” Schumer said during an appearance at the time on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.”

During his recent debate with Democrat Amy McGrath, McConnell reminded viewers that if he lost his reelection bid, the leader of the upper chamber would be from New York — not Kentucky.

Both leaders have also weaponized the Senate’s procedures in recent weeks.

Democrats invoked the Senate’s two-hour rule to prevent the Republican-run committees from holding hearings after the Senate had been in session for more than two hours and Schumer forced multiple votes on motions to adjourn.

Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham (R-S.C), with McConnell’s blessing, put a vote on Barrett’s nomination on the agenda before her confirmation hearings got started and threatened to vote her out of committee on Oct. 22 without a Democratic quorum being present.

McConnell slammed Schumer over his tactics last week.

“The Democratic leader is just lashing out in random ways,” he said, citing Schumer blocking an intelligence briefing “for no reason” and trying “repeatedly to adjourn the Senate for multiple weeks.”

“I understand that some outside pressure groups have been badgering the Democratic leader to act more angry. I’m just sorry for the Senate that he obeys them,” McConnell said on the floor.

The GOP leader also jabbed Schumer for having what he called “a long and serious talk” with Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) after she praised Graham’s handling of Barrett’s hearings and hugged him at the end.

“Scolding somebody for being too civil?” McConnell asked incredulously. “I’m sorry that he feels the need to constantly say things that are false.”

Ross K. Baker, a professor of political science at Rutgers University, said when Schumer took over as Democratic leader at the start of 2017, there was hope that his relationship with McConnell would be better than that of his predecessor, former Sen. Harry Reid (D-Nev.).

Baker, who served three fellowships with Reid, said the former Nevada lawmaker, who was the Senate majority leader when McConnell became the GOP leader in 2007, at first saw his Republican counterpart as a “friendly adversary.” But the relationship deteriorated dramatically over the next 10 years.

Schumer traveled to the University of Louisville in February 2018 to appear with McConnell as part of the McConnell Center Distinguished Speaker Series. Two years later, it’s hard to imagine Schumer making such a gesture of collegiality.

Jim Manley, a former aide to Reid, said Schumer’s relationship with McConnell is falling apart at about the same time Reid’s did, around the four-year mark of working together.

“Schumer has found out exactly what Reid did, which is that it’s impossible to do business with the guy,” he said. “As far as I can tell, the relationship between the two is as broken as it was between Reid and McConnell.”

“What’s going on is yet another indication of how broken the Senate has become,” he added.

Brian Darling, a former Senate GOP aide, said “it was more of a clubby atmosphere” when McConnell and Schumer were first elected to the Senate in 1984 and 1998, respectively, but those days are “over and not coming back anytime soon.”

He added that McConnell and Schumer both are prolific fundraisers who are driven to win and who closely manage their respective caucuses’ political strategies, which makes for an intensely competitive atmosphere.

“They’re both looking over their shoulders at conservatives and liberals in their own caucuses who are pushing for them to dig in and be more partisan,” Darling added.

Story cited here.