San Mateo County, California, was one of the first jurisdictions in the United States to fight the COVID-19 epidemic with sweeping restrictions on social and economic activity. It joined five other San Francisco Bay Area counties in issuing “shelter in place” orders on March 16, three days before Gov. Gavin Newsom made California the first state to impose a COVID-19 lockdown. San Mateo County Health Officer Scott Morrow’s misgivings about reviving that policy are therefore especially striking. “I’m not sure we know what we’re doing,” Morrow confesses in a remarkable statement he posted on the San Mateo County health department’s website this week.

“During the first Shelter in Place order, which I wholeheartedly endorsed, the virus was brand new and had the capability of spreading exponentially due to zero immunity and people’s complete lack of awareness,” Morrow says. The order “was very much consistent with my long-held views about the judicious use of power.…However, I very quickly rescinded my initial orders shuttering society and focused my new orders on the personal behaviors that are driving the pandemic, mainly limiting gatherings, using masks, social distancing, and adopting the State’s framework on business capacity restrictions. Just because one has the legal authority to do something, doesn’t mean one has to use it, or that using it is the best course of action. What I believed back in May, and what I believe now, is the power and authority to control this pandemic lies primarily in your hands, not mine.”

For Morrow, the question is whether broad legal mandates are the best way to encourage compliance with the precautions that help curtail virus transmission. “I look at surrounding counties [that] have been much more restrictive than I have been, and wonder what it’s bought them,” he says. “Now, some of them are in a worse spot than we are. Does an unbalanced approach on restrictions make things worse?”

While Morrow is not sure about that, he believes the recently imposed local and statewide restrictions make little sense. “A hard, enforced [stay-at-home] order will certainly drive down transmission rates,” he writes. “But what we have before us [a proposed county order] is a symbolic gesture [that] appears to be style over substance, without any hint of enforcement, and I simply don’t believe it will do much good. I think people should stay at home, avoid all non-essential activities, wear masks, and not gather with anyone outside their households. I’ve been saying this for about 10 months now. If you didn’t listen to my (and many others’) entreaties before, I don’t think you’ll likely change your behavior based on a new order.”

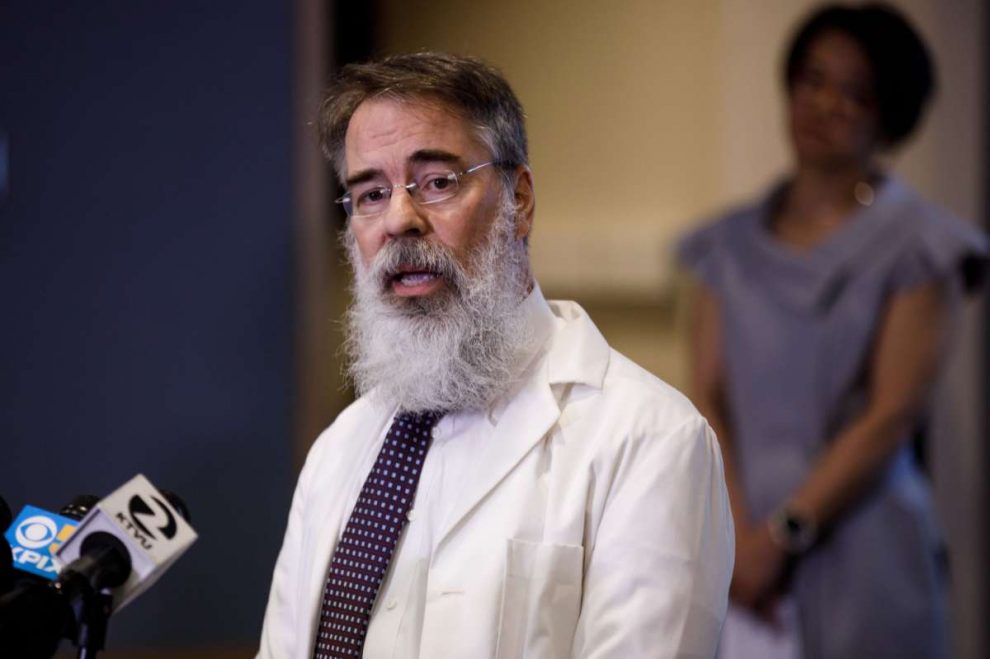

Morrow, a physician with a public health degree who has been San Mateo County’s health officer since 1992, also has doubts about the new restrictions imposed by Newsom. “I am aware of no data that some of the business activities on which even greater restrictions are being put into place with this new order are the major drivers of transmission,” he says. “In fact, I think these greater restrictions are likely to drive more activity indoors, a much riskier [environment]….I also believe these greater restrictions will result in more job loss, more hunger, more despair and desperation …and more death from causes other than COVID. And I wonder, are these premature deaths any less worrisome than COVID deaths?”

Morrow says restrictions on supermarkets and schools are especially worrisome. “I have grave concerns about the unintended consequences of reducing our grocery store capacity to 20%,” he writes. “The [stay-at-home] order will make it more difficult for schools to open or to stay open….I continue to strongly believe our schools need to be open. The adverse effects for some of our kids will likely last for generations. Schools have procedures to open safely even during a surge as evidenced by data.”

More generally, Morrow says, “the new State framework is rife with inexplicable inconsistencies of logic.” He does not elaborate, but a look at Newsom’s latest restrictions, which apply in regions with less than 15 percent unused ICU capacity, suggests several possible examples.

The new rules, which as of today have been triggered in Southern California and the San Joaquin Valley, “prohibit private gatherings of any size, close sector operations except for critical infrastructure and retail, and require 100% masking and physical distancing in all others.” Newsom’s order “instructs Californians to stay at home as much as possible and to stop mixing between households.”

The order closes down “hair salons and barbershops,” other “personal care services,” museums, zoos, aquariums, movie theaters (except for drive-ins), wineries, bars, breweries, distilleries, family entertainment centers, amusement parks, cardrooms and satellite wagering, and sporting events with live audiences. Retailers and shopping centers may admit no more than 20 percent of their capacity. Outdoor dining is banned at restaurants, which are limited to takeout and delivery, but outdoor gatherings for religious or political purposes are permitted. All offices are closed “except for critical infrastructure sectors where remote working is not possible,” but “entertainment production” is allowed.

Outdoor recreational facilities can continue to operate, but “only for the purpose of facilitating physically distanced personal health and wellness through outdoor exercise.” Overnight stays in campgrounds are prohibited, presumably on the same theory that motivated Newsom’s earlier ban on “non-essential activities” between 10 p.m. and 5 a.m. The governor seems to think the COVID-19 virus is especially aggressive at night.

Law enforcement officials across the state have rebelled at enforcing Newsom’s lockdown, especially as it relates to private gatherings and individual movement. Morrow is therefore on solid ground in suggesting that the new stay-at-home orders are largely “a symbolic gesture” that elevates “style over substance.”

Story cited here.