It was feared by many to be the perfect winter storm, a nightmare situation that would push our health service over the edge: the ‘twin-demic’ of flu, which kills about 10,000 Britons every year, and a second deadly wave of Covid-19.

Such was the concern that the Government rolled out the biggest flu vaccination programme in British history.

Thirty million people – 20 per cent more than normal, and now including all over-50s – are eligible for this year’s jab.

Take up of the vaccine is already the highest it has ever been in the over-65s and young children, according to the latest reports.

There’s just one curious problem: flu, it seems, has all but vanished.

The disappearing act began as Covid-19 rolled in towards the end of our flu season in March. And just how swiftly rates have plummeted can be observed in ‘surveillance’ data collected by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Patients aren’t routinely tested for flu, even if it’s suspected, but a number of ‘sentinel’ GP surgeries and hospitals do carry out diagnostic screening on those who have symptoms, and this data gives us the most accurate picture of how much flu is in circulation.

And the figures provide a startling insight into what has become a creeping trend across the world.

In the Southern Hemisphere, where the flu season happens during our summer months, the WHO data suggests it never took off at all.

In Australia, just 14 positive flu cases were recorded in April, compared with 367 during the same month in 2019 – a 96 per cent drop.

By June, usually the peak of its flu season, there were none. In fact, Australia has not reported a positive case to the WHO since July.

In Chile, just 12 cases of flu were detected between April and October. There were nearly 7,000 during the same period in 2019.

And in South Africa, surveillance tests picked up just two cases at the beginning of the season, which quickly dropped to zero over the following month – overall, a 99 per cent drop compared with the previous year.

In the UK, our flu season is only just beginning. But since Covid-19 began spreading in March, just 767 cases have been reported to the WHO compared with nearly 7,000 from March to October last year.

And while lab-confirmed flu cases last year jumped by ten per cent between September and October, as a new season gets under way this year they’ve risen by just 0.7 per cent so far.

Of course, this isn’t the total number of flu cases.

We know from Office for National Statistics data that hundreds of people have been dying from suspected flu-related pneumonia every week throughout the year – that, and the predicted tough winter ahead, is why experts agree that vaccination is still vital to those eligible. Some flu seasons begin earlier than others.

But our low flu surveillance figure does indicate the spread of flu in the UK, right now, has yet to pick up pace.

Other research by Public Health England has confirmed this. Globally, it is estimated that rates of flu may have plunged by 98 per cent compared with the same time last year.

‘This is real,’ says Dr David Strain, senior clinical lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School. ‘There’s no doubt that we’re seeing far fewer incidences of flu.’

So where has flu gone? And what does it mean for our winter?

There are intriguing theories – some more outlandish than others.

There are those who claim flu cases haven’t vanished at all, but are instead being recorded as Covid-19. Sceptics say Covid tests are unable to distinguish between coronavirus and flu, but this is simply untrue.

Dr Elisabetta Groppelli, virologist and lecturer in global health at St George’s, University of London, explains: ‘Flu and Covid-19 are caused by very distinct viruses, and this is clear to see under a microscope.

There’s no chance of mistaking one for the other – the fragment of viral genetic material from the coronavirus looks like a bit of spaghetti, while the flu genetic material we test for looks like eight pieces of penne pasta.’

Another compelling explanation suggests the presence of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19 and has run rampant throughout the world, has somehow ‘crowded out’ the flu virus.

The theory has gained traction on Twitter, and there is some scientific backing for the phenomenon.

When an individual is infected with one virus, they are less likely to be infected by another during that time due to something called ‘viral interference’.

Virus expert Professor James Stewart, at the University of Liverpool, says: ‘Immune system cells come in and help destroy the first infection, and if another virus comes along that same response will fight it off.’

Dr Groppelli adds: ‘Viruses are parasites. Once they enter a cell, they don’t want other viruses to compete with. So the virus already in the body will effectively kick the other parasite out.’

On a population level, it means if enough people have one virus, others will have nowhere to go and cannot spread.

A study by researchers at the US Centre for Disease Control concludes it is at least possible that this has happened in some regions, and that coronavirus could effectively ‘muscle out’ influenza in the body’s respiratory system.

Viral interference may well have been the reason 2009’s swine flu pandemic never took hold in the way many feared it would.

Yale University academics recently suggested the high presence of rhinovirus – the common cold – in the autumn of that year may have ‘blocked infection’ of the deadly H1N1 virus. At the time, the UK Government planned for a worst-case scenario of 65,000 deaths. In the end, 392 died.

The Yale study found human cells already infected with the cold virus were significantly less likely to become infected with H1N1. So could that happen again this year?

Public Health England studied samples taken from about 20,000 people during the first four months of this year, as coronavirus took hold, and found those who had flu were 58 per cent less likely to also have coronavirus.

This may be more to do with behaviour when you have a virus – staying in bed, or not going out – which means you’re less likely to come into contact with another virus, Prof James Stewart explains.

Yet the study also theorised ‘possible pathogenic competition’ between the two, because co-infection – people with flu and Covid-19 at the same time – was strikingly rare.

A Chinese study on two previous coronavirus outbreaks, SARS and MERS, has also shown the same effect. Infection with another virus, such as flu, protects to some degree against a coronavirus infection.

But what isn’t clear, and hasn’t been tested, is what happens the other way around. Can a coronavirus infection, with or without symptoms, elbow-out flu? Dr Groppelli says: ‘The only thing we can say is that, right now, before winter hits, is it’s a bit too early to tell.’

Most scientists agree there was not enough Covid-19 in circulation in March to explain the dramatic drop in flu cases. And the same holds true as we approach winter.

Random testing suggests that, in May, between five and six per cent of people in the UK had corona antibodies, rising to 17.5 per cent in worst-hit London, according to Public Health England.

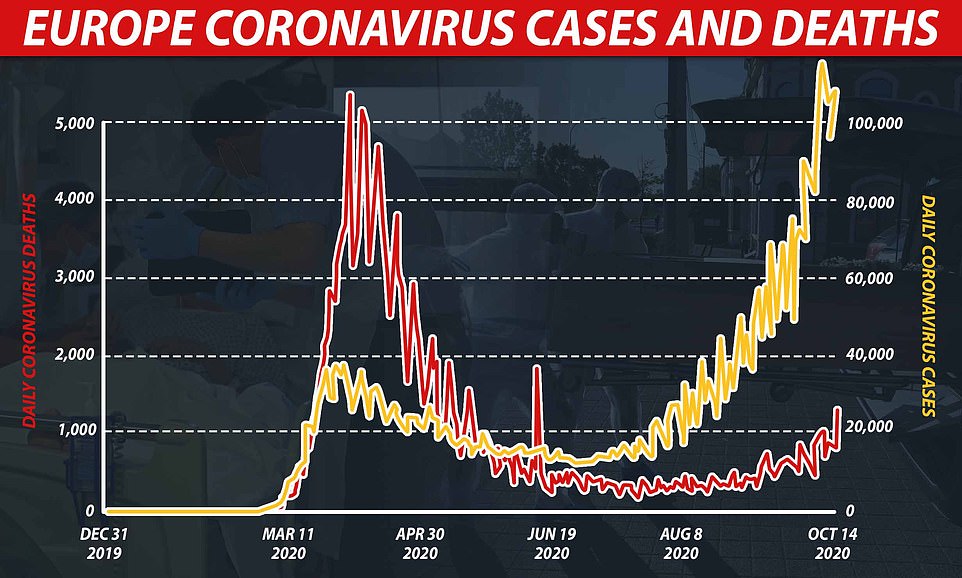

Now cases are rising again, by 90,000 a day, according to the Chief Scientific Adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance.

But Dr Ellen Foxman, who authored the Yale viral interference study, says: ‘One virus can only disrupt the spread of another if enough people have them.

‘When we’re talking about common colds, the rates are astronomically high, and many people are asymptomatic.

‘But for Covid, at present we think only 15 to 20 per cent of people in hard-hit places like New York have been exposed. Most places will be a lot lower than that.

‘That’s not enough for Covid to prevent flu by interference and certainly not enough to account for the huge drops in flu we’ve seen in the statistics.’

Viral interference, typically, would also not have caused such a sudden drop in flu cases, adds Dr Strain.

Instead, scientists overwhelmingly agree the decline is far more likely to be linked to interventions – social distancing, hand-washing, lockdowns and school and shop closures.

‘If coronavirus interfered with anything, it was our behaviour,’ says Dr Foxman.

Both viruses spread in the same way: through infected droplets. But people with Covid are thought to be more contagious, and for longer, that those with flu.

One measure of this is the much talked about reproduction, or R number – the number of people that one infected person will pass on a virus to, on average.

Covid-19 has a reproduction number of about three, if no action is taken to stop it spreading. It means one person would be expected to give it to three others.

Some viruses are more contagious, for instance measles, which has an R number of roughly 15. Flu, on the other hand, has an R number of just over one.

The incubation period for flu is also lower. After being infected with flu, it typically causes illness within two days, compared with five days on average for Covid-19.

That means it’s far more likely that individuals will be going about their business while unknowingly infecting others with Covid-19 than they will if they come down with flu.

It means, Dr Strain says, that even small mitigation measures will have a far greater, and speedier, effect on flu transmission.

‘All of the studies on face masks and social distancing are based on preventing flu transmission and have shown huge reductions,’ he adds. ‘So it’s no surprise it worked.’

Australian officials claim their low flu numbers can be partly attributed to their vaccination programme, which the Government boosted by 50 per cent, ordering 18 million vaccines rather than its usual 12 million.

Australia’s huge geography – 32 times the size of the UK with people more dispersed – combined with strict Covid lockdown measures also played a role.

The total number of coronavirus cases in Australia was around 27,500 in a population of nearly 25 million,’ says Dr Strain. ‘So the idea Covid is crowding out flu – when rates are low and there’s a high degree of compliance to lockdown measures – becomes nonsensical.’

However, there are potentially unintended consequences. As other, milder viruses, such as the flu or common cold, stop circulating as freely, some believe we could have less protection against the more dangerous coronavirus

Dr Foxman says: ‘Common colds probably shore up our defences against other viruses. If we completely shut down transmission of these with lockdown measures, and then open things up again, will we see bigger peaks of coronavirus and other viruses?

‘I’m strongly in favour of mitigation measures, but it’s a big experiment. I’ll be watching closely.’

The other question is whether we can actually trust the flu data at all – most officials say global figures are not robust this year as coronavirus surveillance took priority in laboratories.

Fewer people have also been having appointments for flu-like symptoms during the pandemic, so fewer suspected cases are recorded.

Public Health England confirmed that flu testing has been lower this year. However the body also say that available data does show that overall flu activity is ‘low’.

There is also the danger that, in the absence of testing flu cases in this country and elsewhere, flu cases could be mistaken for Covid-19.

The picture for flu is therefore ‘muddied’, Prof Stewart says.

What happens as we move into flu season is still unknown. Some point out flu deaths might be reduced because many of the vulnerable and elderly have already succumbed to coronavirus. But flu remains a very real risk.

Prof Stewart says: ‘We need to maintain or increase flu vaccination as there will be flu circulating, and if the vulnerable are co-infected then the consequences could be much worse.’

Story cited here.