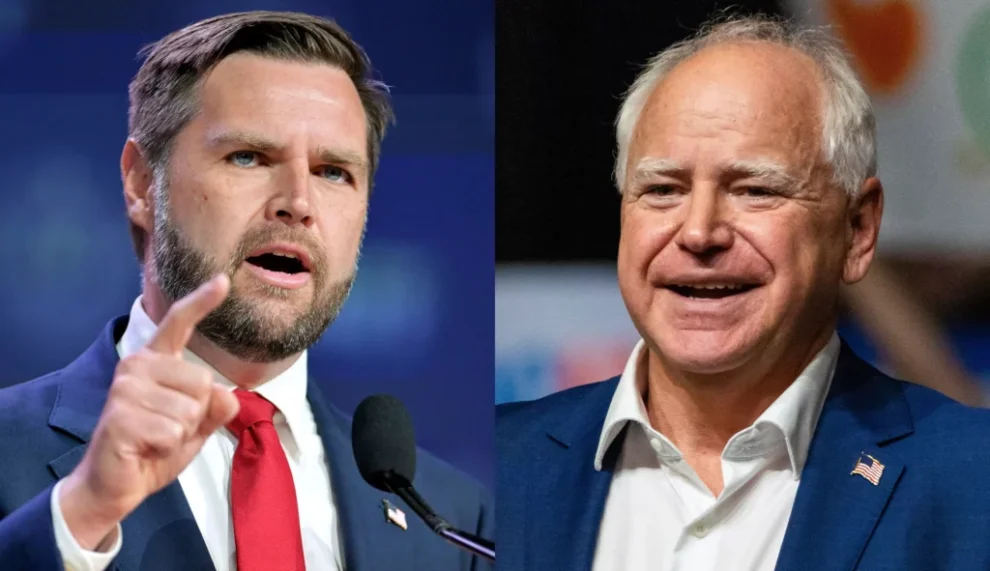

As Sen. J.D. Vance (R-OH) prepares to debate Gov. Tim Walz (D-MN) in their Oct. 1 vice presidential bout, Vance will privately debate a Walz stand-in. Advisers will analyze that exchange and give feedback about what to say, how to say it, and what to avoid like the pandemic.

Those advisers who look to the history of vice presidential debates will likely warn Vance not to freeze up as former Republican Sen. Dan Quayle of Indiana did in his infamous “deer in the headlights” moment during his 1988 debate against his Democratic rival, the late Sen. Lloyd Bentsen of Texas, after Bentsen informed him, “You’re no Jack Kennedy.” They might tell Vance to avoid too many nervous gestures, such as drinking too much water, as then-Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin did in his 2012 debate as the GOP vice presidential nominee against then-Vice President Joe Biden.

Saturday Night Live mocked Ryan’s hydrating by having the actor who played him, comedian Taran Killam, drinking out of glasses that increased in size. For the punchline, he graduated to a hamster bottle.

But the late Rep. Jack Kemp set the gold standard for what not to do in the vice presidential debate in 1996. The 18-year Republican congressman from western New York-turned-HUD secretary had been out of public office for nearly four years when he faced off against the sitting Democratic vice president, Al Gore.

The opening moderator question to Kemp concerned President Bill Clinton’s ethical lapses, a couple of years before the Democratic commander in chief became the first president impeached since 1868 — and ultimately acquitted by the Senate. Kemp invoked the name of his campaign boss, the 1996 Republican nominee, former Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole of Kansas. Kemp declared that it was “beneath Bob Dole to go after anyone personally.” That was all well and good, but “attack dog” has historically been part of the vice presidential nominee’s job.

Gore provided a faux embrace of Kemp, with whom he had been a House colleague from 1979 to 1985, roughly a contemporary in national politics. Gore showered Kemp with flattery from the outset. It worked astoundingly well.

The vice president said he would “like to thank Jack Kemp for the answer that he just gave” and welcomed a “positive debate about this country’s future.” Gore, known for his environmental advocacy, even archly offered Kemp, a professional quarterback in the old American Football League during the 1960s, “a deal.”

Gore continued, “Jack, If you won’t use any football stories, I won’t tell any of my warm and humorous stories about chlorofluorocarbon abatement.”

Kemp took the bait. “It’s a deal. I can’t even pronounce it,” he said, and it got much worse for Republican viewers from there.

One of the controversies in the ether that year was over Baltimore Orioles second baseman Roberto Alomar spitting on home plate umpire John Hirschbeck. It happened after what most baseball observers agree was an awful third strike call and Alomar’s subsequent ejection following an argument over said bad call.

Alomar, born in Puerto Rico, and a future Hall of Fame second baseman, said, without evidence, that Hirschbeck had used a racial slur in their heated exchange. He also brought up the subject of one of the umpire’s children, who had died of a genetic defect.

Major League Baseball suspended Alomar for five games, not immediately, but at the start of the next season. Moderator Jim Lehrer asked Kemp if this was a sign “that something’s gone terribly wrong with the American soul.”

Kemp’s rambling answer turned the incident into a question of capitalism and opportunity. “How in the name of American democracy can we say to Eastern Europe that democratic capitalism will work there if we can’t make it work in East LA or East Harlem or East Palo Alto, California” he asked. He mentioned private property, the rule of law, and wealth creation. He at no point mentioned Alomar.

When it was his turn, the vice president sounded downright human and reasonable.

“You asked about the incident involving Roberto Alomar,” Gore reminded. “I won’t hesitate to tell you what I think. I think he should have been severely disciplined, suspended perhaps, immediately. I don’t understand why that action was not taken.”

Kemp also allowed Gore to use flattery to backhandedly smear the Republican Party as a bunch of racist separatists. The vice president said of Kemp, “I think it’s an extremely valuable service to have a voice within the Republican Party who says we ought to be one nation. We ought to cross all of the racial and ethnic and cultural barriers. I think that is a very important message to deliver.”

Rather than protest on his party’s behalf, Kemp said, “Well, I thank you, Al. I mean that very, very sincerely.”

There had been some debate over who “won” the 1992 vice presidential debate between Quayle, the sitting vice president, and challenger Gore, but there was no question that Gore struggled. He appeared wooden at times. Quayle managed to land too many blows that Gore was not able to return.

Not so four years later. There was near unanimity about the Gore-Kemp debate: Gore simply had Kemp’s number and delivered for his president and party. The Democratic Clinton-Gore ticked walloped its Republican Dole-Kemp rival. And the vice president’s good showing in the 1996 debate set him up to run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2000 with little serious opposition.

To avoid being such a stepping stone, Vance’s advisers will likely tell him to be much more pugilistic toward both his debate opponent, Walz, and Vice President Kamala Harris. His job will be to “tear down that Walz,” so to speak, and Republican voters and donors will be taking notes.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

One thing Vance has in his favor is that he’s hungrier than Kemp was. Kemp was in the twilight of his career in 1996, at age 61. He had been in Congress from 1971-89, representing Buffalo, New York, and was the architect of the Reagan tax cuts. That was followed by four years in President George H.W. Bush’s Cabinet.

Vance, 40, was first elected to the Senate in 2022. He has shown great ambition to reshape the economy in a more populist direction with more tariffs and family tax credits, but, so far, he has few legislative achievements to his name. There’s a small but real chance the vice presidency could give him the leverage he wants. But first, he has to win.

Jeremy Lott is the author of The Warm Bucket Brigade: The Story of the American Vice Presidency.