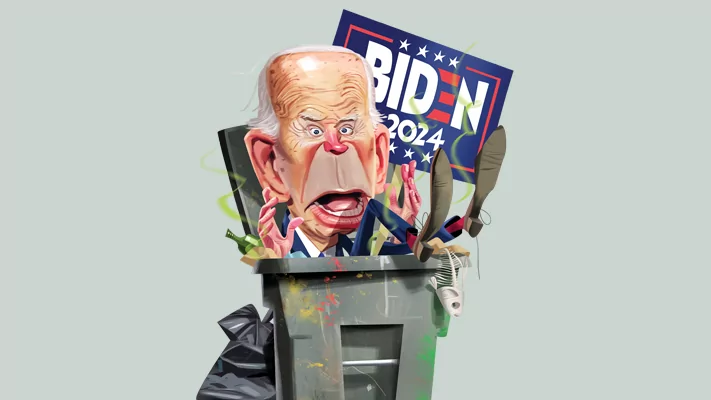

After President Joe Biden’s disastrous debate performance, many Democrats have been mulling the prospect of ditching him as the party’s nominee. As of now, the idea is mainly in the domain of opinion writers in the pundit class. Only a handful of backbench Democrats in the House have openly called to dump Biden. But reports suggest that Democratic politicos are privately wary about nominating Biden at the party’s convention next month. Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) was surprisingly noncommittal about Biden’s candidacy. Could they actually do this? There has been a lot of chatter but not much discussion of how that would really play out.

The answer is yes. Democrats could kick Biden to the curb, although the process could be much messier than a lot of pundits expect. There would be legal and campaign finance concerns that might pose headaches but would hardly be decisive. The bigger challenge is an institutional one — namely, Democrats would be handing total control of their process to the 5,000 or so delegates set to gather in Chicago in late August. That could be extremely unpredictable.

Legal problems revolve around ballot access. Control over who is on the ballot is decentralized in the United States, with determinations made by the 50 states plus Washington, D.C. The Democrats avoided one problem earlier this year when Ohio changed its ballot-access rules. The relatively late date of the Democratic convention meant that the party would not formally nominate its candidate until after the deadline in Ohio had passed, but Gov. Mike DeWine (R-OH) called a special session of the legislature to grant an extension.

Notably, Ohio has a Republican trifecta, with the GOP controlling the governor’s mansion as well as both chambers of the state legislature. And still, it made an allowance for the Democrats. That is a sign that any legal challenges to keep the new Democratic nominee off the ballot probably will not go anywhere. “Democracy” and “norms” have been overused terms in the last few years, but this kind of lawfare would truly strike at long-standing democratic norms. It is highly unlikely any court would bless a challenge to keep voters from choosing between the two major candidates. Democrats might have to spend time and money in court to defend their nominee’s access to the ballot, but they would likely triumph in the end.

HOW BIDEN COULD BE REPLACED AS THE DEMOCRATIC NOMINEE

Similarly, campaign finance issues create hurdles that would slow but certainly not stop any replacement to Biden. The Biden campaign’s cash on hand would go to Vice President Kamala Harris if she became the nominee. Otherwise, federal campaign finance laws prohibit transferring large sums of money from one candidate’s committee to another. However, the then-defunct Biden campaign could transfer the money to the Democratic National Committee or a Democratic super PAC. Those organizations could spend Biden’s funds so long as they did not directly coordinate with the new candidate. They also would not be able to take advantage of the lower advertising rates reserved for candidate committees.

This would be a hassle for the new Democratic nominee, assuming it is not Harris, but hardly determinative. The money could still be spent on the campaign, even if it does not quite get the same bang for the buck as it would if it were held by Biden or Harris. And anyway, a new nominee would not struggle for money. This is not the 1960s, when the Democratic Party depended almost exclusively on organized labor for its cash. The upper rank of today’s Democratic Party is wealthy, culturally elite, and politically engaged. Its donors have the means and the motivation to support a new nominee.

The biggest issue is an institutional one, namely the how of selecting the nominee. That power technically belongs to the delegates of the Democratic National Convention, although in practice they have followed the results of the primary system for the last 50 years. Delegates are formally bound to do so, but substantively, there is a lot of leeway. The rules of the party state that delegates must follow the results of their primary voters “in all good conscience.” That loophole is large enough to drive a tractor-trailer through as it basically means delegates could revolt even if Biden were to stay in the race.

Suppose Biden continues to insist he is staying in the race but gives another poor performance, akin to his debate showing in June. Or suppose the press find definitive evidence that Biden is suffering from a serious medical condition such as Parkinson’s disease, yet he refuses to drop out. It is not hard to imagine party delegates declaring they cannot support Biden in good conscience. This is likely why the Biden campaign is pushing to have delegates nominate him in late July, via a Zoom call. Once Biden gets the imprimatur of the party delegates, the path to replacing him becomes much more perilous. Otherwise, delegates could still revolt against Biden up to the final roll call in Chicago at the Democratic National Convention.

If Biden were to withdraw from the race, he could encourage his delegates to vote for a candidate of his choosing. But they would be under no legal obligation to do so. And the Democrats would find themselves in a spot no party has faced since 1968. The decision as to whom it nominates for president is in the hands of the delegates, who would in this case be totally sovereign — not even bound by the milquetoast conscience clause.

To say that such a scenario would be unpredictable is a massive understatement. The parties nominated candidates in this manner, delegates meeting in convention, from the 1830s through the 1960s. That is replete with surprising results from such conclaves, as early front-runners often began strong but then saw their momentum stall as they struggled to clear enough delegates, and eventually fell to defeat. Occasionally, it would take a staggering number of ballots to choose a nominee, with the record being 103 ballots for the Democrats to choose John Davis in 1924.

Such a protracted impasse is much less likely now because back then, a candidate had to win two-thirds of the delegates to secure the nomination. Since Franklin Roosevelt had the rules changed in 1936, candidates need only a simple majority. Harris would thus have an edge in such a contest, but it might not be decisive. It is quite possible that, without a unifying figure like Biden to corral them, Democrats break into their various factions and constituencies, with each promoting a candidate of its own. Harris could probably build a majority coalition, but perhaps the doubts many in the party have about her abilities would keep her from pulling it off. In that case, the nominee would be an unexpected candidate, a “dark horse” as they used to be known.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

To be sure, dark horses were atypical in the era of party conventions. The usual result was that there would be maybe one or two front-runners and the delegates would choose among them. But conventions periodically did reject a front-runner and choose an unexpected alternative. James Polk, Franklin Pierce, Rutherford Hayes, James Garfield, and William Jennings Bryan all won their party nominations in the 19th century even though nobody went into the conventions expecting to vote for them. In most cases, these surprise candidates only won after a protracted and tumultuous battle on the convention floor.

If the party abandons Biden as the nominee, there is a small but not insignificant probability of such a result. It would be a marvel to watch for anybody who appreciates the history of American politics — a kind of window into a world long gone by. But for Democrats, who would have to bind the party together in advance of a general election just over two months away, it would be less than ideal. For the last half a century, the convention has not been the place where a party actually chooses its nominee but is a showcase for its unity behind the candidate and its vision for the future. Swapping Biden out in Chicago next month could be divisive and ugly.

Jay Cost is the Gerald R. Ford senior nonresident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.