The Handmaid’s Tale burst onto the TV scene eight years ago and launched its sixth and final season earlier this month. From the start, it is an exercise in blunt-force storytelling, eschewing moral subtlety in favor of a didacticism intended to remind progressives of their inherent goodness. The Sons of Jacob, rulers of the Christian-nationalist dystopia called Gilead, are evil. They have replaced America with a slave state dedicated to systematic sexual assault. Those who resist, led by protagonist June Osborne (Elisabeth Moss), are righteous. And into one camp or the other, every character goes.

Even in its early seasons, the series is ridiculous: a bloated, hysterical attack on exactly the wrong target. Yet even conservatives have to admit that its world-building is not without the occasional point of interest. The program’s costumes, particularly its resistance-appropriated handmaid robes, are overdetermined, improbable, and deeply stupid. It’s geopolitics, less so. Forced with other young women into rape-abetted gestational surrogacy, June hopes, in an early episode, that a visiting Mexican delegation will carry her to freedom. Alas, no. The Mexican officials have come not to liberate handmaids but to purchase some of their own. As for Canada, its humane treatment of refugees gives way, by Season 4, to a nascent pro-Gileadean sentiment.

Why is this bad behavior on the part of still-liberal democracies? The answer has to do with the central fact of the near future that Hulu’s series imagines. Childlessness, once a lifestyle choice or correctable pathology, has become the world’s all-consuming political problem. As the Mexican ambassador confesses to June, her Boston-sized hometown hasn’t produced a baby in six years. Whatever one thinks of its totalitarian regime, Gilead possesses fertile women, a reality that scrambles diplomatic norms and assessments. If, as one Gileadean commander tells another, “the human race is at risk,” can nations really afford to thumb their noses at the one society that still bears “fruit”?

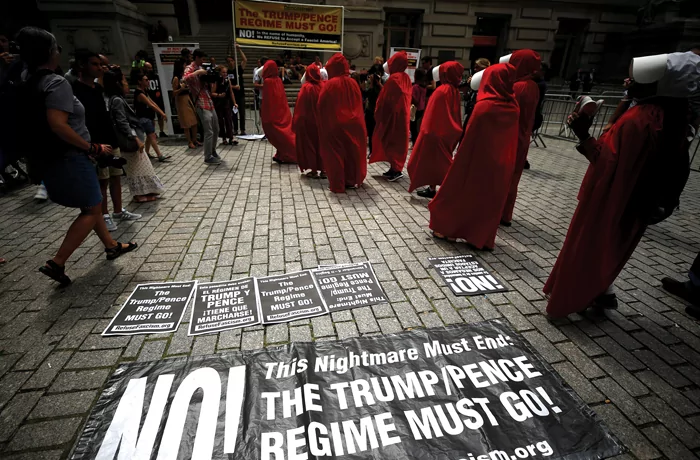

Of course, critics have long overlooked this element of the composition of the series, preferring instead to frame the show as a feminist corrective and rallying point. However, one wonders how that discourse might have been different if the Season 1 premiere occurred now instead of in 2017. In those paranoid days, America’s commentariat could think of little but Donald Trump and the “evangelicals” who swept him into power. Nearly a decade later, by contrast, the developed world’s fertility crisis has begun at last to break through the noise.

One needn’t be a media scholar to imagine the shift in tone. Then, The Handmaid’s Tale is a terrifying exploration of “Biblical fascism” (The New Yorker) and “industrial-grade misogyny” (The Ringer) in “Trump’s America” (the New York Times). Today, it is at least conceivable that the show would be seen for what it has, in its strongest moments, always been: one possible reply to the query, “What happens to societies when there aren’t any more children?”

That Western democracies (and non-democracies) will eventually have to answer this question is now an article of faith among population experts. Far from replenishing themselves with new births, developed nations have allowed their fertility rates to drop so far below replacement level that “there’s a very real possibility we’ll need to reinvent society,” the left-leaning demographer Leslie Root recently told The New Yorker. What that remodeling will look like is, of course, anyone’s guess, and making decades of predictions is a fool’s errand. I hope and trust that nations will not set up rococo-breeding cults, such as in Hulu’s dystopia. Yet we shouldn’t be surprised if, say, Chile (1.54 births per woman) outlaws contraception, Italy (1.24) discourages female secondary and postsecondary education, or South Korea (0.78) forces its citizenry into the countryside and away from family-unfriendly Seoul. These would be extraordinary measures undertaken by the truly desperate. The erasure of whole people would be worse.

To its credit, The Handmaid’s Tale takes seriously the kinds of choices that might be made by countries facing national extinction. Yet even this somber work has been hampered by a critical establishment that can’t see past its own ideological obsessions. Take, for instance, the program’s pusillanimous waffling on the matter of race. Unlike Margaret Atwood’s source novel, in which black Americans are “resettled” outside of Gilead, Hulu’s series rightly judges that even incorrigible bigots would ignore skin tone in a dying world. Or at least it does so until Season 3 when a high-ranking commander declines to accept a handmaid “of color.” What changed? Presumably, the show’s creators read the dozens of think pieces condemning the series’s post-racialism as “harmful” or “naive.” Even diabolical police states, it would seem, are beholden to the logic of intersectionality.

Nor has the show always practiced intellectual honesty. A moving Season 2 sequence, for example, follows a commander’s wife on a diplomatic mission to Canada, where couples kiss on the street, women contribute to society, and normal life continues uninterrupted. Left unsaid is the fact that this progressive paradise will cease to exist in two or three generations. Indeed, generations are the very thing that Canada lacks. They cannot be tolerated, affirmed, or diversified into being.

As for the new episodes, they are as dreary and plodding as ever, incapable of any mode but instruction, and committed primarily to the reiteration of previously made points. Having escaped Gilead two seasons ago, June spends the final stretch working for a resistance group and pursuing a love triangle with her husband and a Gileadean informant. Viewers of Season 5 will recognize many of the beats. The series remains, furthermore, a weird girlboss melodrama, addicted to outrageous score-settling and increasingly neglectful of its one important subject. Sure, humanity has a mere 50 years to go, but why do that math when you can film eight hours of “Nevertheless, June Persisted”? If they haven’t put that slogan on a T-shirt yet, it’s only a matter of time.

Graham Hillard is an editor at the James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal and a Washington Examiner magazine contributing writer.