MONTREAL — Canada’s brief election season is already coming to an end after just five weeks of campaigning.

The Liberal Party, led by Prime Minister Mark Carney, is hoping to maintain its mandate. The Conservatives, led by Pierre Poilievre, are hoping to seize power after a decade of sitting on the sidelines.

Bloc Quebecois, a federal party that only runs in the French-speaking province of Quebec, isn’t focused on governing Canada — they’re hoping to eventually escape it.

100-DAY REPORT CARD: TRUMP TORNADO SHOCKED AMERICA — AND THE WORLD

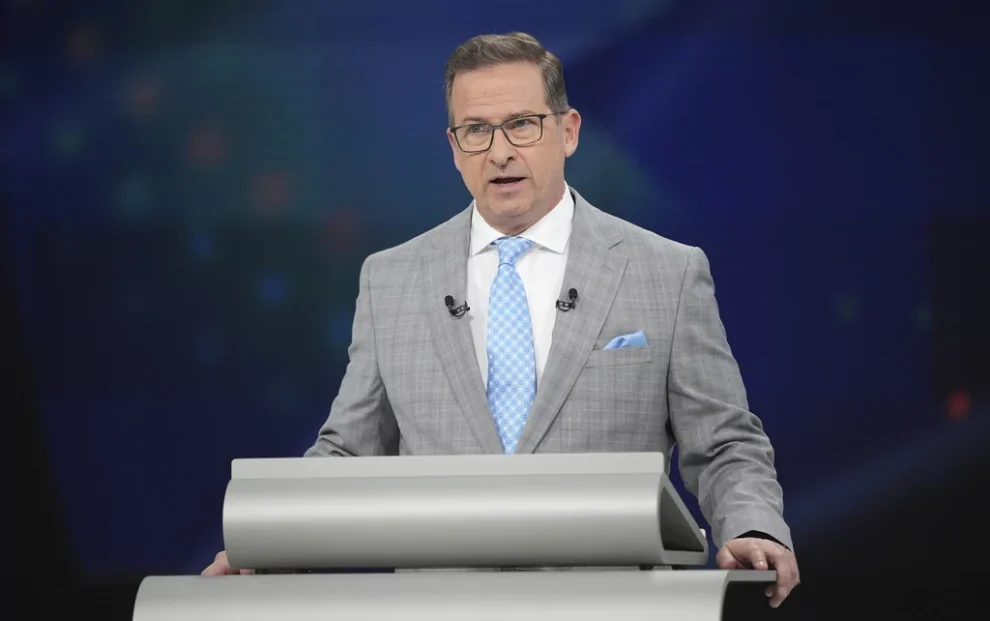

“We are, whether we like it or not, part of an artificial country with very little meaning, called Canada,” party leader Yves-Francois Blanchet said on Friday during a campaign stop in Shawinigan, Quebec.

The Quebec native previously described his House of Commons seat as membership in a “foreign parliament” because “this nation is not mine.”

His comments drew furious rebukes from his federal election rivals who accused him of denigrating the nation.

Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston published an open letter to Blanchet stating that Canadians “should all be proud of Canada for our freedom. For our safety and security. For our democracy. For our free healthcare.”

Blanchet was unphased. He clarified that while he does believe “Canada is an artificial country,” that observation is “not meant as an insult.”

The phrasing was indelicate, but the idea that Canada lacks a cohesive identity is not a novel proposition. Former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau himself, who stepped down earlier this year after almost ten years leading the country, famously called Canada a “postnational state.”

JOE CONCHA: THE MEDIA WANT PRESIDENT AOC, BUT REALITY SAYS OTHERWISE

“There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada,” Trudeau told the New York Times in 2015. “There are shared values — openness, respect, compassion, willingness to work hard, to be there for each other, to search for equality and justice. Those qualities are what make us the first postnational state.”

Canadian leaders pride themselves on the fact that their country is not an American-style “melting pot” in which immigrants are expected to meld into the existing culture. Instead, they see their society as a “salad bowl” in which distinct and different cultures make up a bigger whole without the need for blending.

For supporters of Bloc Quebecois, escaping the salad bowl is a matter of survival.

Depending on one’s perspective, their passion for “Quebec nationalism” is either a niche obsession or a righteous battle.

“I prefer the word ‘independence,’ and our plan was never a radical one,” Simon-Pierre Savard-Tremblay, a member of Parliament with Bloc Quebecois, told the Washington Examiner. “We are not revolutionaries. We are not radical left-wingers. We are a quite moderate movement.”

Savard-Tremblay is running for re-election in the federal district of Saint-Hyacinthe—Bagot—Acton, a rural region approximately an hour away from Montreal. In the House of Commons, he serves as vice chairman on the Canada-U.S. Inter-parliamentary Group and used to be vice chair of the International Trade Committee. He speaks fluent English, but is dogmatic on Quebec’s French identity.

He spoke with the Washington Examiner while attending an art exhibition at the local shopping mall and speaking with voters just two days ahead of the election.

“In Quebec, we use the word ‘nationalism’ but not in the same sense that you use it in the U.S.,” Savard-Tremblay said. “It is similar to what you call ‘patriotism’ in the U.S. But being proud of our nation is not a left-wing or a right-wing issue. And I think [having] our own country is not a left-wing or right-wing issue.”

The first referendum for Quebec to separate from Canada was held in 1980. The public decisively voted against the proposition, 59.6% to 40.4%.

The province held a second referendum in 1995 that ended in a historically narrow loss. Approximately 50.58% of citizens voted to stay, winning by a margin of just 1% — fewer than 55,000 votes.

Quebec nationalists believe that at the right time and under the right circumstances, a third referendum will be the charm. In their minds, federal Parliament seats and debates with the rest of Canada are only a temporary burden until their fellow Quebecois wake up and join the movement.

President Donald Trump is disrupting that long-term plan.

The president’s harsh trade tariffs and proposal to bring Canada into the United States is stoking Canadian patriotism in some Quebecois hearts, threatening to push them to the mainstream parties out of concern that the wrong candidate could threaten the entire country’s future.

FULL LIST OF EXECUTIVE ORDERS, ACTIONS, AND PROCLAMATIONS TRUMP HAS MADE AS PRESIDENT

Bloc Quebecois won 32 districts in Quebec following the 2021 federal elections, beating the Conservatives’ 10 seats but falling behind the Liberals’ 35 seats in the province.

Early election predictions from the CBC claim the Liberals and Conservatives are likely to both make gains in Quebec at the expense of the Bloc.

Salvation from the White House’s aggression is central to both parties’ appeal to the public, but Savard-Tremblay is not impressed.

“The Liberals’ strategy was kind of ‘Don’t let Carney speak too much, just let Trump speak.’ That was their strategy. They were playing on the fear of our constituents,” the parliamentarian told the Washington Examiner. “So they did a very quiet campaign, not with too many promises.”

He continued, “I don’t really understand what [Poilievre’s] strategy was, because at first he said ‘No, I’m not Trump, Trump is harmful to Canada, I don’t like him, I’m gonna be against him.’ But now, since last week, he is moving more to the right.”

Savard-Tremblay sees a cruel irony in fellow citizens’ sudden concern over national sovereignty when his movement has been denigrated for decades while seeking the same opportunity for themselves.

“It’s kind of funny to hear Canadian elites talk about ‘sovereignty, sovereignty, sovereignty’ when they are neglecting it for Quebec,” Savard-Tremblay said. “They are fighting Quebec sovereignty but now they are speaking about saving their own sovereignty.”

In 1977, Quebec passed the Charter of the French Language. The legislation, commonly referred to as Bill 101, is a defining law of the province that recognized French as the “only common language of the Québec nation and that it is essential that all be aware of the importance of the French language and Québec culture as elements that bind society together.”

Subsequent court battles have modified and weakened the charter in practice, but the French language’s special status in the province remains.

Just over 84% of the Quebec population is French-speaking, according to the Canadian government. Approximately 15% is English-speaking, and 46% is bilingual. No other province even comes close to these demographics, making Quebec the de facto advocate for French speakers across Canada.

French is practically the only usable language in rural areas Saint-Hyacinthe—Bagot—Acton. But metropolitan areas are much different.

A foreign tourist in downtown Montreal might believe that the French-language signs are just a superficial affectation of the city. Pedestrians on the street converse in English. Posters stuck on streetlight posts are written in English. Waitresses and hotel staff effortlessly switch out of French after an initial “bonjour.” Even the graffiti is anglophone.

Enter the Quebec Office of the French Language — a government agency dedicated to combating the lingua franca invasion.

Their most recent target? Hockey fans.

WHAT IS DOGE? WHAT TO KNOW ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT EFFICIENCY

Bars across the province were packed with hooligans this week as the Montreal Canadiens, colloquially known as the “Habs,” played against the Washington Capitals in the NHL playoffs. “Habs” is a shortening of “Habitants,” a demonym for the early French Canadians that settled modern Quebec.

The Habs previously missed the post-season three years in a row and city pride was now on full display.

During such occasions, Montreal Transit Corporation (STM) buses were expected to show the team’s battlecry — “Go! Habs Go!” — on their digital displays. But that didn’t happen.

Last year, a citizen complained to the Office of the French Language about a similar use of the “Go!” slogan on city buses in support of CF Montreal, the city’s soccer team.

“Since the word ‘Go’ is considered an anglicism, the STM committed to removing it from bus signs,” said Montreal Transit Corporation spokeswoman Isabelle Tremblay.

Instead, buses displayed the French translation: “Allez! Canadiens Allez!”

“This maintains team spirit while complying with [French language laws],” the spokeswoman explained.

The alternative was linguistically correct, but alien to fans. It enraged many fans in Montreal — especially those who weren’t particularly committed to defending French primacy.

Eventually, the outrage became unignorable. Jean-Francois Roberge, the province’s French-language minister, took to social media to announce the agency would not be taking future complaints about the “Go!” chant.

“It’s a unifying expression, rooted in our history, and part of our cultural and historical specificity,” Roberge added on social media platform X. “It’s a Quebecisme and we’re proud of it!”

Even Bloc Quebecois knew when to pick its battles, and this was not one of them.

Blanchet weighed in to say that while he personally did not use the English phrase, he didn’t think it was wise to crack down on its usage.

RUBIO SAYS CHILDREN’S DEPORTATION LEFT ‘UP TO THEIR FAMILIES’

“It might not have been the best of ideas to say, ‘Don’t say, Go Habs Go.’ Personally, I don’t remember myself screaming that in the Bell Centre, but it never offended me,” he said.

A bilingual city in an English-speaking country will inevitably drift toward English. A province that does not require French fluency from its citizens will inevitably drift away from the language. Enforcing strict language laws keeps French relevant, but it creates an antagonistic relationship.

It’s unlikely these trends will change under the current Canadian system. Bloc Quebecois believes that for Quebec to remain French in perpetuity, it will eventually need to take control of its own destiny.

The Monday election will reveal whether the party will retain its support despite national panic over Trump’s existential threats.

If they do, separatists will continue to use their seats in the “foreign parliament” to continue their crusade for independence.

Miles away from Montreal in Saint-Hyacinthe, Savard-Tremblay is likely to keep his seat.

TRACKING WHAT DOGE IS DOING ACROSS THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

Asked whether he believes an independent, sovereign Quebec is possible in his lifetime, he smiled.

“Yes, of course,” he said. “That’s why I’m into politics.”